Is Trump coming after Medicare? White House, Dems try to claim upper hand on health care debate: ANALYSIS

President Donald Trump has promised repeatedly to protect Medicare and Medicaid, the popular health care programs for older and low-income Americans, even tweeting last fall that “Democrats will destroy your Medicare and I will keep it healthy and well!”

It was a promise that started in the early days of his presidential campaign.

Then came this week’s 2020 White House budget request. That plan called for hundreds of billions of dollars to be trimmed from Medicare in the next 10 years, with estimates ranging from more than $500 billion to $845 billion depending upon the accounting.

On Medicaid -- the federal health care program for low-income Americans -- Trump’s plan would shift more than $1 trillion in federal money to limited, state-run block grants that analysts warned wouldn’t keep pace with inflation.

While both proposals were quickly pronounced dead-on-arrival in Congress, Democrats immediately tried to push the idea that only their party would protect health care for seniors and the poor. Trump's top health policy aide countered that reforms were necessary to keep Medicare solvent -- foretelling the debate to come in the 2020 elections.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi suggested the president was more focused on "campaign applause" than substance.

“These are massive cuts,” declared Rep. Anna Eshoo, D-Calif., at a hearing Tuesday.

“The president’s budget doesn’t match the values of the American people,” added Rep. G.K. Butterfield, a North Carolina Democrat.

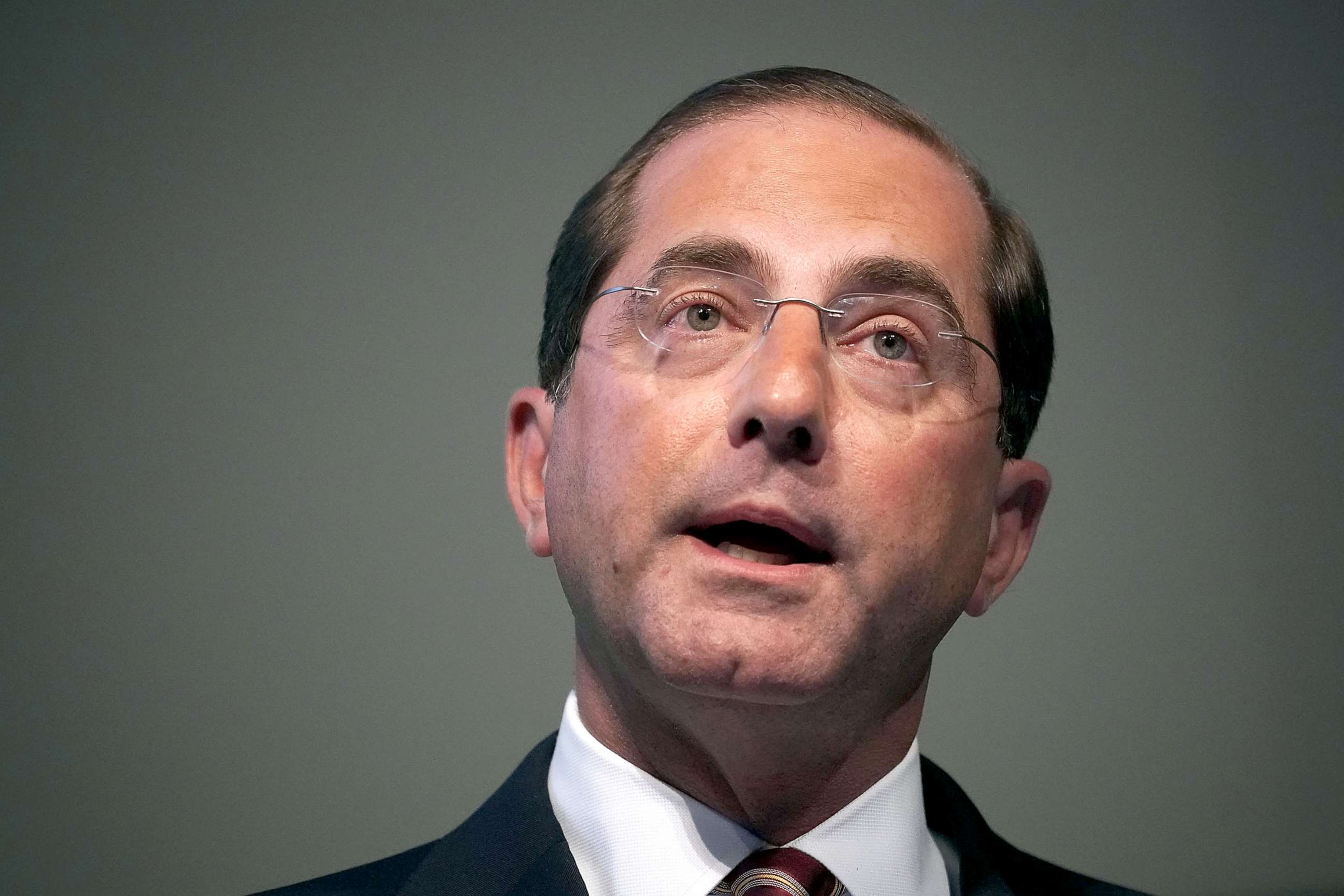

Trump’s Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar on Tuesday tried to assure lawmakers seniors wouldn’t be directly affected. He noted the budget would find savings by reforming how Medicare pays providers like hospitals and argued the plan would extend the solvency of the program.

“On Medicare, we’re actually putting it on a sounder footing for the future,” Azar told the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

“Hospitals are gobbling up doctors’ practices and jacking up the rates,” he added.

Rodney Whitlock, a longtime Republican staffer on Capitol Hill, said that in recent years administration budgets -– and Congress’ response to them -– have become mostly partisan affairs rather than a starting point in real negotiations.

Medicare, in particular, he said, is a favorite topic because so many Americans support it. The program, which provides health insurance to some 60 million seniors and people with disabilities, represents some 15 percent of the federal budget.

“Rhetoric around Medicare goes from zero to 60 in microseconds,” said Whitlock, now a health care lobbyist with McDermott+Consulting in Washington.

Tricia Neuman, senior vice president and director of the program on Medicare policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, said whether the administration’s proposal can hurt or help seniors in the long run is a much bigger issue that would have to take into account a number of factors. And it probably would impact different groups of people in different ways, such as capping drug prices for some but not others, she said.

Also, what qualifies as “waste” in any federal program often is in the eye of the beholder, she noted.

“This begs the longer term question of how to finance care for an aging population,” Neuman said. “The country hasn’t really engaged in a serious discussion” on that.