Trump administration's changes to Clean Water Rule could have wide-ranging impact

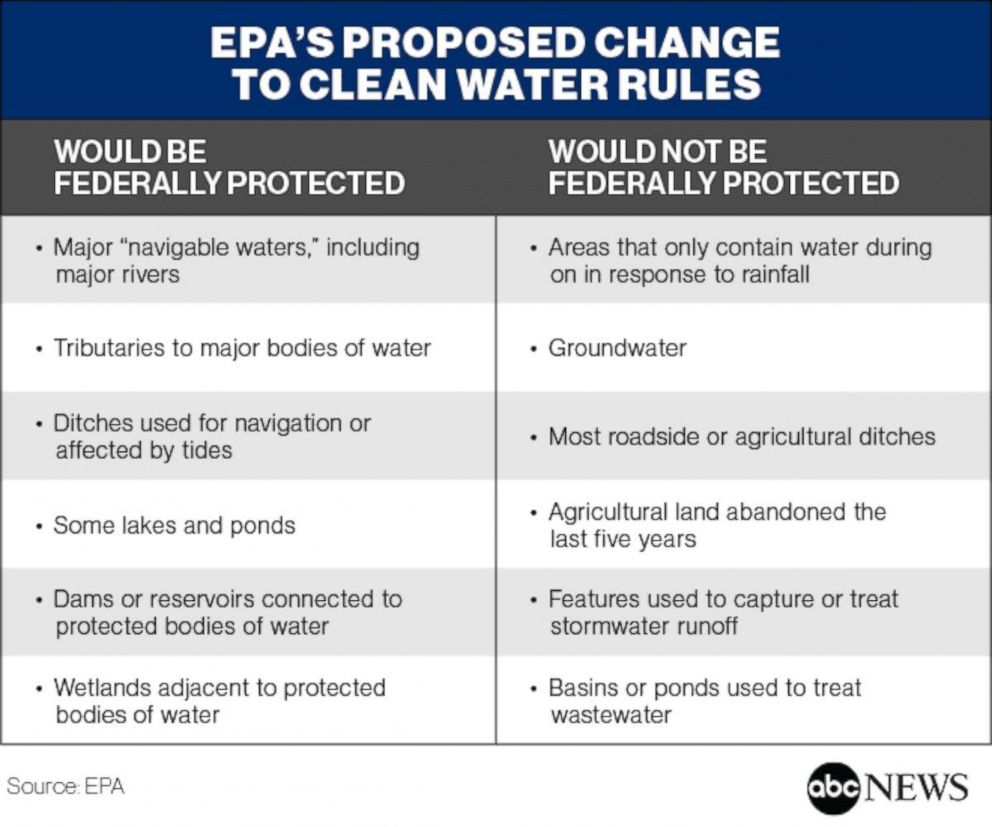

The Trump administration is planning a major change to a clean water rule in the United States, exempting certain types of creeks and bodies of water from federal protection in a move that may have wide-ranging impacts.

The proposal -- a campaign promise to farmers who say the regulation created too many regulatory burdens -- would remove federal protection on bodies of water like creeks and streams that are only wet after it rains, but federal officials do not have data on the number of bodies of water it would impact.

The change would also reduce protections on wetlands that aren't connected to larger bodies of water.

"Our goal is a more precise definition that gives the American people the freedom and certainty to do what they do best, build homes, grow crops, develop projects, then improve the environment and the lives of their fellow citizens," said EPA Acting Commissioner Andrew Wheeler.

The new definition of what counts as a "Water of the United States" is intended to clarify years of legal wrangling over the rule, which at this point is effective in some states but not others. Trump has often said the Waters of the Unites States rule, known as WOTUS, had such a beautiful name but was a disaster, citing concerns from farmers and developers that it put too many restrictions on their work.

American Farm Bureau President Zippy Duvall and representatives from farm bureaus in all 50 states attended the rule signing Tuesday. Farmers have widely criticized the previous WOTUS rule, saying it was expensive, imposed too many restrictions, and duplicated state and local rules.

It's unclear exactly how many streams or creeks the rule would impact. Previous EPA estimates found that about 60 percent of streams in the U.S. flow inconsistently due to rain on seasonal changes, but not all of those would be impacted by the new rule. That number includes both streams that only flow after it rains, known as ephemeral, and intermittent streams that can be impacted by seasonal changes or groundwater. Ephemeral streams would no longer be federally protected under the Trump administration's proposal but not all intermittent streams would be impacted equally.

Dave Ross, assistant administrator in the EPA's water office, said they know how many bodies could lose federal protection under the proposal because that data doesn't exist.

"Right now there really isn't a map that shows how many are in our out," Ross told reporters on Monday.

But he said EPA will be working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, states, and tribal leadership to collect data to map out the changes. An EPA spokesperson confirmed there are generally more non-perennial streams in the west and southwest parts of the country. Some states like California already have strict clean water rules on the local level, but other states may not have as many resources to enforce rules as the federal government.

Ross said the Trump administration's proposal is more legal than scientific, saying EPA went through multiple Supreme Court cases going back to 1985 to inform the proposed new rule. The proposal includes a new method of planning for flood events that will include more recent data, but they did not do any modeling on the impacts of climate change on drought conditions, flooding, or rain events and how that could impact bodies of water when drafting the new rule.

"I think that probably tells you everything you need to know about this rule is that it's probably a political line-drawing exercise," said Blan Holman, a clean water expert with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Holman said advocates are concerned about areas like the San Pedro River in Arizona, which relies on ephemeral streams for as much as half of its water flow.

"Do you really want somebody dumping pollution into one of these creek beds that that day is dry but then it's going to rain the next day and then it's going to wash into the San Pedro River?" he told ABC News.

He also said the Southern Environmental Law Center estimates a majority of wetlands in South Carolina could be at risk of losing protections under the proposed rule, depending on the specifics of the rule, which have not yet been released. Wetlands provide crucial habitat and help control flooding and advocates are concerned the looser protections will open them up to development.

The EPA's proposal will be posted for 60 days of public comment.