Travel nurses: Heroes who left their families behind to fight on the frontlines of the pandemic

When the pandemic first struck and millions around the world holed up inside, travel nurses across the country packed their bags, kissed their families goodbye and left everything behind to offer critical support on the front lines.

DaKoyoia Billie, a mother of four from Stockbridge, Georgia, is one of them. She’s been working with COVID-19 patients for the last year.

Billie said the job was daunting as the virus shut down the U.S., where more than 29 million have been infected and at least 527,000 have died.

Leaving her family in the midst of the uncertainty wasn’t easy.

Watch the full story on "Nightline" TONIGHT at 12:35 a.m. ET on ABC

“I've never wanted to completely be away from my kids and my husband for such an extended, long period of time,” Billie said. “When I'm leaving again, it's always, ‘When will you be back?’ You know, ‘When should we expect you?’ … You can tell by, you know, how tight the hugs are.”

Last April, she headed to New York City, then the epicenter of the nation’s pandemic.

“For traveling nurses, those on the outside looking in see, ‘Oh, she’s going for a vacation, oh she gets to be away from all the chaos.’ In actuality, you know, that suitcase means I don’t get a chance to be with my family every day of the week,” Billie said. “I don’t get a chance to hug my kids or to kiss my husband every day of the week. And so, it’s a challenge and it’s a sacrifice that not everybody’s willing to make. It’s just that I’ve been chosen to make it.”

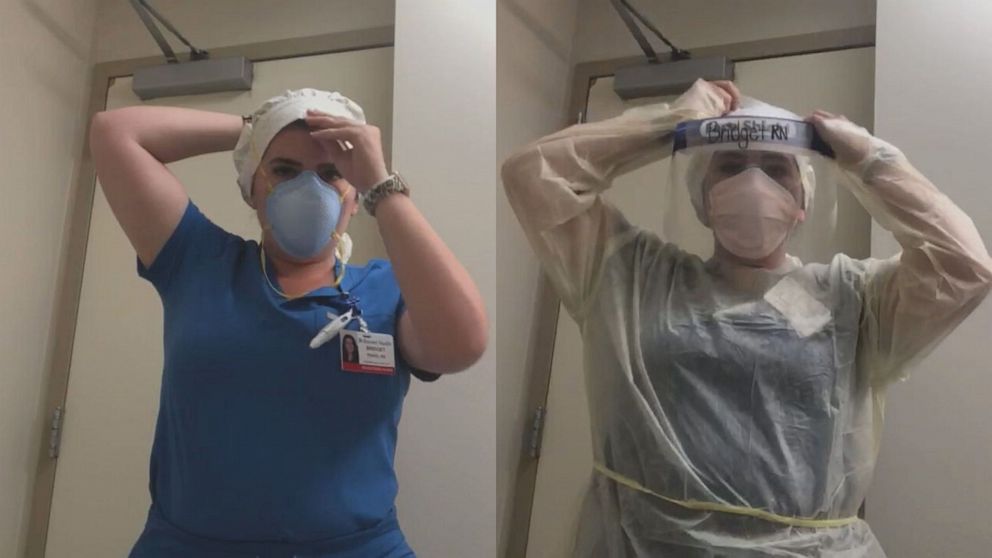

Bridget Harrigan is another travel nurse who rose to the challenge in the early days of the pandemic.

“Honestly, I love everything about travel nursing, but sometimes I’m on an assignment for only a couple of weeks and I’m already thinking, ‘OK, I’m a little far from home or I kind of miss my family,’” she said.

When she first heard about COVID-19, she was on assignment in Denver.

“I started seeing on all of my nurse travel pages, hearing from my friends that Washington, Chicago and New York were begging for nurses,” she remembered. “It all just happened so fast and it changed the course of travel nursing immediately.”

Travel nurses often criss-cross the country to aid hospitals in need, especially when facilities in their hometowns need immediate help.

“Then, of course, these COVID-19, government-paid assignments were very attractive to people because you were able to create opportunities in your life that you weren't before, like providing for your family in a way that you never could as a staff nurse back home,” Harrigan said.

Some travel nurses during the pandemic earned more than $50 an hour, plus housing accommodations, according to a report from nurse.org.

Harrigan and Billie are two of thousands of nurses who travel from hot zone to hot zone during the pandemic. Choosing to travel can be lucrative, with travel nurses often making more than staff nurses.

Harrigan and Billie recorded video diaries documenting their travels, trauma and victories during their travel assignments.

Despite the risks, some travel nurses say they want to work in the most dangerous of health care war zones. In the battle against COVID-19, that meant inundated emergency rooms and intensive care units.

“I've always wanted to be in a place where I could make the biggest impact,” Billie said. “The pandemic was no different. And so, that meant going to the hot zones.”

New York City and ‘the epicenter of the epicenter’

Billie gave birth to twins in December 2019. Just a month later, the first COVID-19 case in the U.S. was reported in Washington state, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“I figured, OK, this is serious. It's not going anywhere. ... I still need to help provide for my family. So, do I do that by staying here and putting them at risk, or do I go away and work where I'm not coming home and bringing this unknown virus back home?” Billie said.

Billie chose to leave her family -- 16-year-old son Jaylen, 4-year-old Elijah, and newborn twins Karrington and Kingsley -- behind to keep them safe.

“As long as I have [personal protective equipment], then the safest place for me to be right now to keep my family safe is away,” she said.

Her first assignment, in New York City in April 2020, was “very scary,” she said. At that time, the city had reported 203,000 cases of COVID-19 in the Big Apple alone from March to May, according to the CDC.

She said she saw seven to 12 patients daily.

“Early pandemic was very scary,” she added, “because we were still learning things about this virus.”

At the time, the death toll was so overwhelming there wasn’t space for the bodies.

“There were two trucks out back, you know, with deceased patients,” Billie said. “[We] just didn't have a place to send them. And every time we'd have to pass by, you'd think about the lives lost and the families that were hurting. You think about your own family.”

Working in a pandemic, especially so soon after giving birth, was exhausting.

“The twins were about 3 months old. I was pumping because they were premature,” Billie said. “My co-workers were amazing. They would even remind me, ‘Hey, isn't it time for you to pump?’ They were just fascinated I was able to still pump and mail milk. I mean, they were huge boxes. I made sure I mailed it every week.”

Billie’s husband, Marcus, said he was prepared to make things work.

“This hasn’t been our first rodeo with travel nursing,” he said. “She did it a few years back. She went to Boston. She has gone to California. So it wasn’t foreign.”

But this time there were new challenges -- remote schooling for their older children, in addition to caring for the newborns. He said the help of family members and nannies proved crucial.

The family has relied on video chats to stay connected.

“Early morning FaceTimes were very short and sweet and to the point. ‘Hey, I'm headed off to work. You know, I'll talk with you some time during the day when I get a moment.’ But the most important times were in the evenings, when the kids had a chance to settle there from school,” Billie said.

Harrigan also flew to New York during the most dire days of the pandemic there.

“I knew I had to go -- there was no question about it at the time,” Harrigan said.

She worked out of Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, dubbed “the epicenter of the epicenter,” for a grueling eight weeks straight.

“It was the one that was on the news for bringing in the chilled body trucks because we ran out of body bags and we ran out of room,” she recalled. “It was the one on the news with them nurses filming themselves, crying in the corner, not being able to communicate the trauma that they were experiencing, not being able to handle the amount of death we were experiencing.”

The experience, she said, became “surreal.”

“I was there for about eight weeks. And I worked almost every single day of those eight weeks, so most of the nurses who came in on those buses who flew in from all over the nation were contracted to work every single day in a row for however long their contract was,” she said.

Day after day, Harrigan saw hospital rooms filled with patients and watched them fight for their lives.

”I'm a very emotional person. I'm definitely a crier. During this pandemic, I think, I really recognize the trauma that I'm building up because I wasn't crying. There was no purging of emotions for me, especially in New York, whenever it was. Sleep, work, eat, sleep, and that was it, I had no time to grieve,” Harrigan said.

The trauma caused her to dread her days off, worried about leaving her patients alone but also fearing that if she were alone herself she’d be overwhelmed with grief.

“I dreaded my days off because I had time to feel and I had time to experience my emotions. Then I began to dread my days off for an entirely different reason, because every single time I had a day off, my patient would pass away,” Harrigan said.

“We all began to have that anxiety and fear of coming back to work, to empty beds, or in most cases full beds with different faces. Because we would lose everybody,” she said. “There were already plenty of people to take their place.”

Though initially gripped by terror in New York, she began regaining hope.

“My first two weeks was terrible, were terrible. Then by week six through eight, it really started to slow down. And by that last week, it really did not feel like I was needed as much anymore,” she said. “There was a light at the end of the tunnel. Our time was finished there. They didn't need our help anymore.”

On the road again: Harrigan in Arizona

Harrigan went home to Texas for two weeks after her stint in New York. But by the end of her break, she had already decided to take on a new assignment in June in Arizona, where cases were rising.

“They were expecting this to be the next New York. I told my parents, ‘Sorry, but I’m going to do this again, because if that’s true, even if that’s a little bit true, I need to help again and they’re going to need it.’”

Though she only planned to stay for four weeks, she extended the trip when the situation worsened.

Part of her routine in Arizona included “decontaminating” herself after returning home from work.

“This is my decontamination station,” she demonstrated. “I try to put it as close to the door as possible so I’m not really coming in. I leave my shoes here … after they’re wiped off. One by one, I just kind of take off articles of whatever I’m wearing, like my name badge, anything that’s attached to me or my scrubs, and I clean it off on this station. It’s wiped down and disinfected, and I leave it to dry and then I can kind of move it over to the side with my clean stuff.”

Harrigan said Arizona was decimated by COVID-19 because “nobody took it seriously.”

“It was pretty indicative of a lot of other states as well. They watched New York City kind of crumble at the time when COVID-19 first hit them,” she said. “They maybe had three cases while New York City was losing people by the thousands. And when I first got to Arizona, a lot of the health care workers that were already there told us that the reason it was getting bad is because nobody's taking it seriously.”

The tremendous loss of life, so tremendously quick, was staggering.

“I've never experienced … five to 10 deaths in just a shift before. I've never experienced that gravity of the situation,” she said. “Sometimes all I was doing was holding a hand because ... there was no treatment left to do for that patient, and they're a human being.”

Helping patients mend from the vicious virus is just one part of the job -- protecting yourself from infection is another hurdle for front-liners.

“I was about two weeks into my assignment and I started to feel badly. I believe my first symptom was general fatigue and just feeling run down,” said Harrigan, who contracted COVID-19. “They ended up expediting my results because I'm a health care worker. And then I immediately went to my hotel room in a city [where] I did not know a single other human being, a 12- to 14-hour drive away from my family, and I stayed in my hotel room for 14 days. It was very scary for me.”

“I started crying and I realized it was because I had told my very sick patients that I would be back the next day and I wouldn't be back for at least 14 days. And they were surely not going to be there when I returned,” she added.

It was at that breaking point that her family urged her to let them drive from Houston to Phoenix to see her.

“I told her every day I was OK, even when I wasn't, because in my head, I knew if my mom showed up here, she would end up in the hospital and she may not make it -- and there's no way I'm letting her do that,” Harrigan said.

Harrigan spent eight weeks in Arizona.

On the road again: Billie in Texas

After returning home to Georgia on May 22, she accepted a new assignment on July 4 and deployed on July 7 “in Texas. That was the next state that was hurting for assistance at the time,” Billie said.

She, too, felt fatigue after endless days of trying to help save patients, often unsuccessfully.

“I think people are mistaken about what I do here and how challenging it can be,” she said. “I mean, I'm not out here having fun and partying after work. My days literally consist of work out, go to work, talk to my family, go to sleep. And I do it all over the next day -- sometimes seven days a week.”

For Billie, her mission of helping people in the most dire circumstances is personal. She says the challenges she’s faced throughout her life prepared her for the COVID-19 crisis.

“You're going to a completely unfamiliar place. You have to make associates and friends, and I've made large decisions, big decisions, major decisions my entire life,” she said. “Deciding to travel was nothing different. I always tell myself that I only know how strong I am when all I have to be is strong. When that’s my only option, I know what I have to do.”

When Billie’s mother was in prison for eight years, she was raised by her grandmother. She gave birth to her eldest son when she was a high school sophomore.

“However, I had the support of my family, of my church family, and I knew what I had to do: I graduated with honors from my nursing program, went on to grad school,” she said. “Whenever I'm faced with a challenge or something that seems difficult for somebody, or impossible for the next person, this is familiar for me. Like, I know what I have to do,” she added.

Billie returns home, then returns to New York

In September both Billie and Harrigan enjoyed a moment of respite when their assignments ended and they could go home.

Billie said her warm welcome, being smothered in hugs and kisses, made the hard days apart worth it.

“It was great to know that they remembered my face, even from our FaceTimes. I had the 4-year-old on one leg, and then I have my 16-year-old, you know, with his arms around my neck,” she recalled. “It was great.”

“Each time she comes home from an assignment, it is definitely like Christmas,” her husband said. “And it's extra special each time.”

Though parting from her young twins was challenging, Billie said she’s grateful she had enough time with them as newborns to see them walk.

“I had a chance to be there, you know, and help encourage them to walk. So that was very special,” she said.

She spent her days back home enjoying the outdoors with her kids, watching them dance and do handstands.

But soon she had to return to work -- on the road again.

“There are many times where I find myself getting frustrated, trying to juggle being a mom and being a wife and being a provider. However, I'm constantly reminded of why I do what I do,” Billie said.

In October, Billie returned to New York City, where she said she felt a renewed sense of purpose.

“It’s good to be back in New York to continue what I started back in early April,” she said. “New York is at the forefront of COVID.”

Billie woke at 5 a.m., and she usually worked 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. on the team that carried out testing at LaGuardia Airport.

The pandemic was a bit more tempered in October compared to Billie’s first time on the ground in New York. Thanks to advances in testing and safety restrictions, she could visit home once or twice a month.

On one special trip home, she returned to her family in Georgia to celebrate her birthday. She said she had her son “create a calendar, and he's able to cross off the days for which I'm able to return home.”

Harrigan returns to Houston -- then ships out for Guam

Harrigan left her assignment in Arizona and almost immediately jumped back into action in Houston, where her family lives, in September.

“My dad, he has this running joke now, asking me if I take more than four hours off in between jobs now, because I really don't,” she said. “At first, it felt really great and wonderful to be near my family because for this assignment, I was working nights and I worked five nights a week. So I had two days off and I was like, oh, my gosh, two days off a week. This is a vacation. This is wonderful.”

On her days off she’d see family and enjoy dinner with them on their back patio. But soon, with infections skyrocketing, she couldn’t see them anymore.

“Then the job really picked up [and] that got very busy and draining, physically and emotionally,” she said. “I would just go back to my hotel room and sleep instead of meeting up with my family for something. So it became very seldom that I actually saw my family, who was literally 25 minutes down the road.”

Harrigan also returned to work in New York for an assignment in the same hospital system she started out in at the height of the pandemic there.

She says the “atmosphere was very different, but still somber.” However, she says the New York healthcare systems “were able to drastically, monumentally decrease [COVID-19] numbers.”

By February, Harrigan took an assignment in Guam, a U.S. island territory near the Philippines.

“I started to see some posts about Hawaii and Guam assignments at the time, and I had told myself, ‘Oh, my gosh, I need that,” Harrigan recalled. “Emotionally, it's been rough, and I've been afraid to allow myself personal time because personal time is emotional time. It has, thankfully, been more time to heal. And that's a big reason why I decided to take it, because for a whole year, it has been time to grieve and not time to heal.”

Sacrificing to save countless lives

Despite the personal hardships -- the stress, the being away from family, the witnessing unimaginable loss of life -- both Harrigan and Billie said it was worth it.“To all the other travel nurses, all of the other nurses and general, I mean, if people haven't said it enough, thank you,” Harrigan said. “Because you're needed, you're wonderful, you're fighting through some terrible traumatic experiences over this last year, and in many cases you're leaving your families behind.”

Billie said that despite everything she’d do it all again.

“I would,” she said. “When you hear those patients thank you for just being here, thank you for leaving your family, to help a family that you don't know, thank you for sacrificing your time, thank you for the long hours, thank you for offering reassurance, I would most certainly do it again.”