Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes returns to the stand in fraud trial

Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes will return to the stand on Monday at her criminal fraud trial in a California federal court.

Holmes, who is accused of defrauding investors out of millions as she raised money for her blood-testing start-up, is expected to testify on Monday and Tuesday on direct examination, her attorney Kevin Downey said -- meaning prosecutors likely won't have their shot at questioning her until after the long Thanksgiving weekend.

Holmes' defense team surprised a packed courtroom on Friday, when they called their client to testify just hours after prosecutors rested their case, eliciting exclamations from the audience as they craned their necks to get a better look at the former Theranos CEO.

A maskless Holmes, who had once graced the covers of magazines and had been hailed by some as the next Steve Jobs, smiled as she told the jury about the origins of her company -- the brainchild of the Stanford dropout who had vowed her blood-testing technology would shape the future of health care.

Holmes is the third witness to testify in her defense. She faces nine counts of wire fraud and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud, for allegedly misleading investors and patients about Theranos' blood-testing device.

She has pleaded not guilty to all charges and faces decades behind bars if convicted.

On Friday, Downey asked her if she ever believed Theranos had developed technology capable of running any blood test -- a question at the heart of the prosecution's case, which sought to prove that she intended to defraud investors with false information.

"I did," she told the jury.

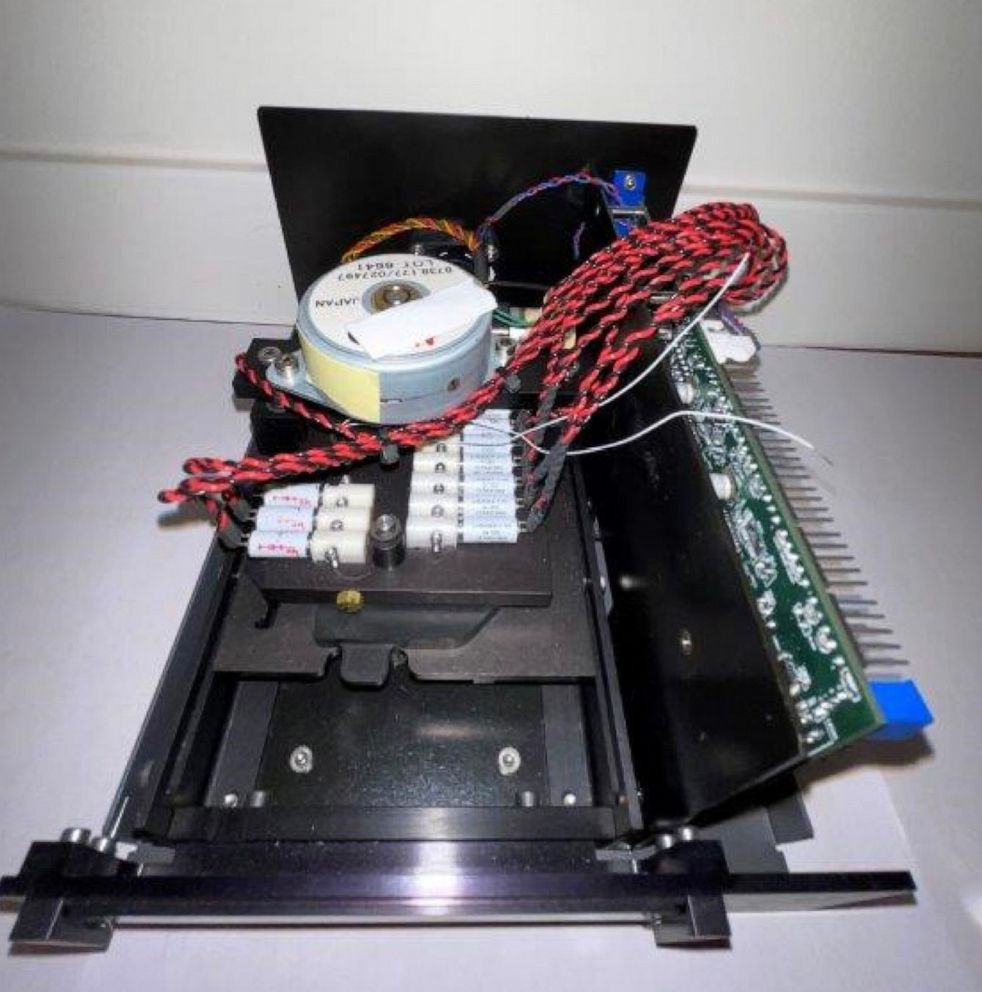

"We worked for years with teams of scientists and engineers to miniaturize all of the technologies in a laboratory," she added, referring to how Theranos had created the small blood-testing machines of which iterations were dubbed the "Edison" and the "miniLab."

Back in 2009 or 2010, Holmes said, Theranos had a breakthrough: The technology, she claimed, was capable of performing any kind of blood test.

During the 11-week trial, prosecutors asked investors whether they knew at the time of their investment Theranos' miniature lab device could only run 12 assays, or blood tests. Many of the former stockholders said they did not know that.

Holmes acknowledged on Friday the miniature device only offered 12 types of assays, but said she did not always limit her public comments on the capabilities of Theranos tech to what was available in its clinical lab.

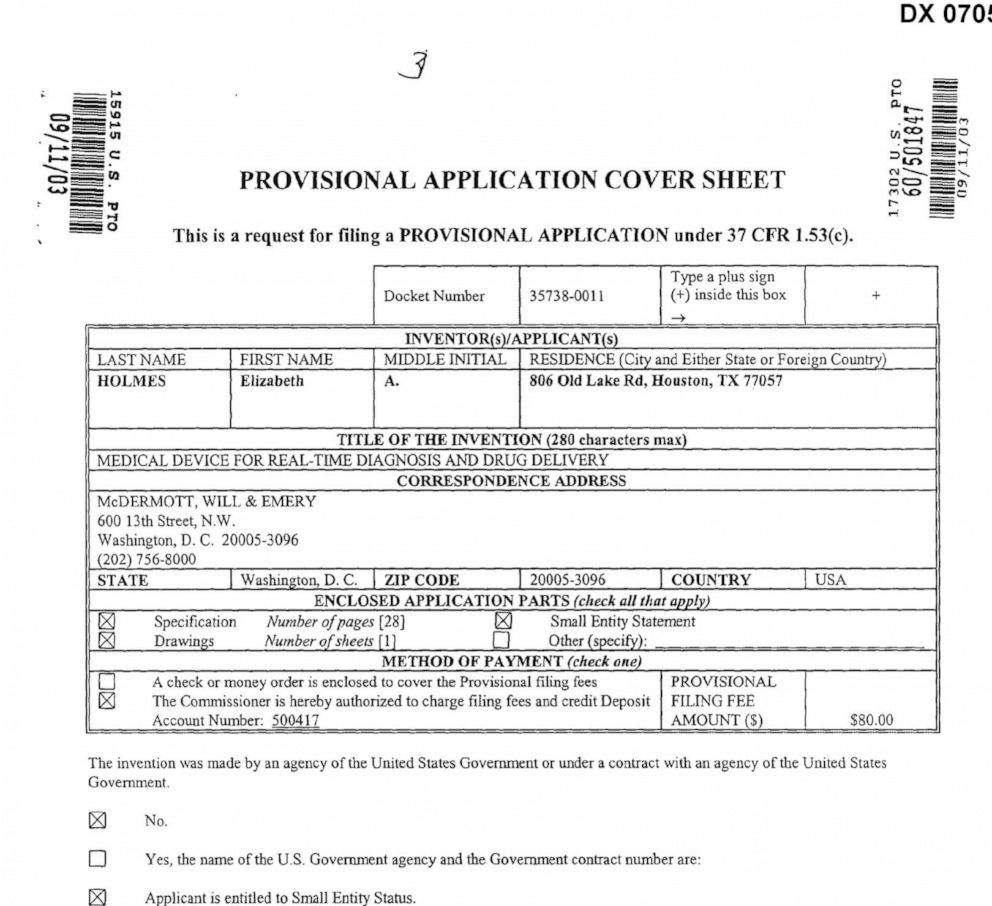

Holmes then took jurors back to 2003, the summer after her freshman year at Stanford University, when she filed her first patent for a pill or a patch, which she envisioned could read a patient's blood and administer certain medications to them accordingly.

When she returned to Stanford for her sophomore year, she brought the patent to chemical engineering professor Channing Robertson, whom she said was skeptical at first but encouraged her to continue her research. Her parents had even let her take the money they had saved up for her college to apply it to her work on the patent, she testified.

By March 2004, Holmes had dropped out of school to pitch her patent idea to pharmaceutical companies for potential use in clinical trials, and started her own company.

"I met with everyone I could who knew someone who worked in pharma or was in pharma to try to understand what they did and what they would be interested in," she told the jury.

Yet she found they weren't interested in a pill or a patch, so Holmes said she created a rough blood-testing prototype with "little white pumps" and "valves," which Downey showed a picture of to the jury.

Holmes then honed her prototype, and in 2005 began to sit down with prominent investors, including famed Silicon Valley venture capitalist Don Lucas, her dad's college friend.

Holmes pitched Lucas on her technology. It was a success: Lucas invested and became the first chairman of the Theranos board of directors, where he would remain until January 2013. Her former professor, Robertson, also became a board member.

Holmes went on to strike deals with pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline in 2006, she said. She also put on a demonstration for Novartis in Switzerland.

"We nailed this one. You all did an incredible job in making this happen -- this is the Theranos way," she later wrote to her team in an email, which Downey read out loud in court.

Once Holmes completes her direct testimony, she will likely face questions about various documents she sent to investors, including two apparently doctored reports with Pfizer and Schering-Plough logos emblazoned on their pages, according to Santa Clara law professor Ellen Kreitzberg.

Witnesses from both pharmaceutical companies testified earlier in the trial that they did not approve or have any knowledge of an approval of their trademark on those reports.

"My first reaction was surprise. But as I thought about the reason [Holmes] might [testify] it is she needs to convince the jury herself," Kreitzberg told ABC News. "And so, it may be her only chance of getting acquitted, even though it runs some very high risks."