Telemedicine is having a moment. How can patients make use of the growing industry?

A mask and an iPad. That’s what a patient displaying symptoms associated with the novel coronavirus is handed when they arrive at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

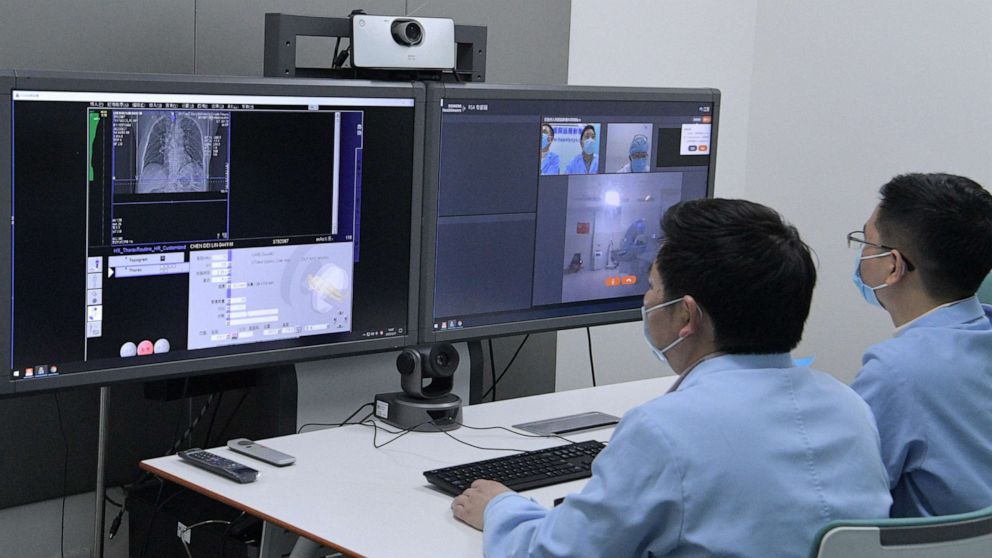

From an isolation room, the patient can then use their iPad to video chat with a remotely-located nurse practitioner who can evaluate their symptoms and determine next steps -- all without a face-to-face interaction. The process is called tele-triage, and it is just one of several ways telehealth is revolutionizing patient treatment in the coronavirus era.

From symptom-checking text bots to more traditional video chat consultations, telemedicine is having a moment -- and it’s a moment industry leaders say is a longtime coming.

"This crisis has supercharged interest and opportunity in telehealth on both the patient side and the provider side," said Dr. Ryan Arnold, an Omaha-based orthopedic surgeon at OrthoNebraska. "I feel like this is accelerating a trend that was going to happen regardless. And it’s going to be here to stay on the back end."

Medical professionals across the board agree that broad-scale telemedicine could help solve many of the problems confronting the American health care system as it struggles to stay afloat amid the crush of COVID-19 cases.

"What telehealth can do is help both the clinicians as well as the consumer have access to service without actually getting exposed to the virus," said Ann Mond Johnson, CEO of the American Telemedicine Association (ATA). "It mitigates the risk. So in that regard it’s incredibly valuable."

Physicians have already begun using telemedicine to communicate with patients remotely via video chat. Patients who do so are less likely to contract or transmit the disease than if they were to visit the doctor’s office in person. Dr. Danielle DeHoratius, a dermatologist in Pennsylvania, began consulting patients this way soon after the coronavirus outbreak. One of her patients contacted her about a rash around his eyes, and said he had come into contact with the virus.

"This patient was quarantined and I was able to see him over telemedicine. Then I was able to send his prescription to a pharmacy that delivers," DeHoratius said. "So I really felt like I made a small impact in reducing the transmission of coronavirus because he didn’t have to go out of the house to see me."

Remote care also preserves personal protective equipment that is already in critically short supply at many hospitals around the country.

"[Access to telehealth] is very important for clinicians and providers who, over the coming weeks, will face considerable strain on their time and resources," said Seema Verma, the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said this week.

For doctors, telehealth holds potential financial benefits. Consultations often take less time than in-person visits, meaning physicians can treat more patients throughout the day. Dr. Judd Hollander, head of Jefferson’s Strategic Health Initiative, said 20 doctors fielded more than 1,200 telemedicine calls in one day last week.

Jefferson’s next step is rolling out a "chat bot that can screen out low-risk patients" as part of an effort to allow doctors to "focus attention on the patients who need something more," Hollander said.

Something similar already exists. A company called Conversa has developed a symptom-checking messaging bot. Users can text "VIRUS" to 839-73 to learn whether their symptoms warrant further care and get information about providers in their area.

For some time, industry advocates have encouraged patients and providers to adopt remote-access consultations. But progress has been slow.

"Generally the regulations have not kept up with the technology," said Ann Mond Johnson, the ATA chief. Bureaucratic red tape at both the state and federal level, she and others said, has made it onerous for providers and app developers to create telehealth platforms that conform to regulations.

The federal government in recent weeks has taken steps to change that. Verma announced Tuesday that Medicare would now cover all telemedicine calls. The administration also waived strict patient protection rules that limit how patients can interact with doctors. According to the new guidelines, providers can now communicate with patients using commonly-used platforms like FaceTime and Skype.

Experts hope these changes will endure and spur growth in an otherwise niche corner of the health care industry.

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

The American Medical Association (AMA) estimates that while physicians' use of virtual visits has doubled over the past three years, only 28% of doctors reported using telemedicine in 2019. A recent survey conducted by Amwell, a private telehealth company, indicates only 8% of patients have had a telehealth visit with a doctor.

One of the primary barriers is simple: awareness. According to a J.D. Power study, only 17% of Americans are even aware that their health system or insurance provider offers telemedicine coverage. Older people -- those most at risk of contracting the coronavirus -- showed little interest in virtual visits. Only 5% have had one.

Another roadblock is insurer coverage. Until the coronavirus outbreak, most major insurers reserved coverage of telemedicine to older, rural patients with limited access to nearby health care facilities. But as the need for remote access to doctors has increased in recent weeks, most insurers -- to varying degrees -- have adjusted their postures.

"Before this happened, the reason telemedicine didn’t grow more is not because patients don’t love it -- they love it, the experience in our data is phenomenal," Hollander said. "It didn’t grow because nobody was paying for it."

Insurers have already begun to reconsider. Blue Cross and Blue Shield, United Health, and Anthem have agreed to cover all telehealth consultations for the next 90 days. Cigna and Aetna said they would do the same through May 31.

With private insurers on board, telehealth is now more accessible than ever. But some say they haven’t gone far enough. Dr. Hollander took issue with insurers setting an end date for their telehealth coverage. As a result, he said, "we’re going to end up with the same problem the next time something happens."

"Right now patients are going to experience telemedicine -- and they’re actually going to like it. And maybe they’ll put pressure on the [insurance] payers," Hollander said. "But the [insurance] payers all realize how short-sighted it was not to offer telemedicine before, and yet even now they aren’t willing to commit to offer it later."

Still, telehealth advocates remain hopeful. By 2030, the ATA projects that 50% of medical consultations will be conducted by virtual means. Until recently that projection seemed ambitious to industry insiders. But the coronavirus, they suggest, could be a catalyst in spurring its widespread use.

"Now that patients and health care providers alike are experiencing telehealth there will be no turning back," said Ann Mond Johnson of the ATA. "And as we come out of this health crisis, telehealth will be a mainstay of our system and accepted for what it is – not telehealth but health."