Teen sent to juvenile detention for not completing homework speaks on ‘injustice’

A Michigan mother and her teen daughter, who spent 78 days in juvenile detention after a judge ruled that she'd violated probation by not completing her homework, are speaking out about their experience, which they say was an injustice in the criminal justice system.

Wishing to be identified only as Grace -- her middle name -- the now-16-year-old, who is Black and has attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, had struggled to keep up with the transition to remote learning during the coronavirus pandemic last year. She was placed on "intensive probation" in April 2020 after being charged with assault for fighting with her mother and larceny for stealing a schoolmate's cellphone after her mother took hers away.

Grace, who lives in suburbs outside of Detroit, said that she knew there would be consequences for those actions, but she didn't realize they would rise to such a level, and that she thinks they did because she's Black.

"If a white girl were to steal the phone and she has the same history as me, same background, same everything ... they would probably look at her and say, 'Hey, you know, you're not brought up like this,'" Grace told ABC News' Linsey Davis. "But for me, I feel like it was more of an 'OK, this is what we expect from Black people.'"

Charisse, Grace's mother who also asked to use her middle name, called her daughter's incarceration an "injustice" that should "not be forgotten ... that should never occur again."

"My daughter was penalized because of having a learning disability, which is her chronic ADHD," Charisse told ABC News.

Stream ABC News Live Prime weeknights at 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. ET at abcnewslive.com.

Among the terms of her probation was a requirement that Grace complete all of her schoolwork on time. But she said the transition to virtual learning made her feel overwhelmed and anxious. She was matched with a caseworker who Charisse said she thought would help Grace get the support services she needed.

"When we first met, she had shared with us that one of her roles would be to help us through any issues, to keep my daughter on the straight and narrow," Charisse said. Instead "I got a violation," she said.

Within days of hearing Grace might have been behind on her schoolwork, the caseworker referred her to the court, recommending that she be placed in juvenile detention, according to ProPublica, which first reported the case. The Oakland County Family Court Division did not respond to ABC News' request for comment.

On May 14, Grace was subsequently brought before Oakland County family court Judge Mary Ellen Brennan, who at one point during the hearing said Grace was "a threat to the community." She ordered Grace to be taken into custody and sent to a county detention center named Children's Village. Her decision came after Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's coronavirus-related order to keep juveniles out of detention unless they posed "a substantial and immediate safety risk to others."

"If we called every person who's taken something or a person who's [gotten into] an argument with their mom ... I'm pretty sure everybody would be ... a threat to the community," Grace said.

Jonathan Biernat, one of Grace's lawyers, said that in the handling of her case, the court never got "any testimony from the school or the teacher -- anybody involved with her education. They got testimony from the probation officer, the prosecutor. And the judge made her decision based on that testimony."

Reporter Jodi Cohen, who investigated Grace's case for ProPublica, told ABC News that 42% of youth referred to the court in the county where Grace lives are Black despite Black youth making up only 15% of the county's population.

"Cases like Grace's, and others where you see young people of color … disproportionately represented at various contact points, to me, that points out systemic failures long before the court involvement started," said Jason Smith, executive director of the Michigan Center for Youth Justice. "We wouldn't be talking about disparity rates at the confinement level if there was more support in the community. ... we wouldn't rely on the justice system to address a lot of these issues that shouldn't be criminalized in the first place."

Charisse said she's still haunted by the memories of her daughter being handcuffed and taken into custody.

"I was devastated. It just didn't make any sense and I became very angry. I was furious," she said.

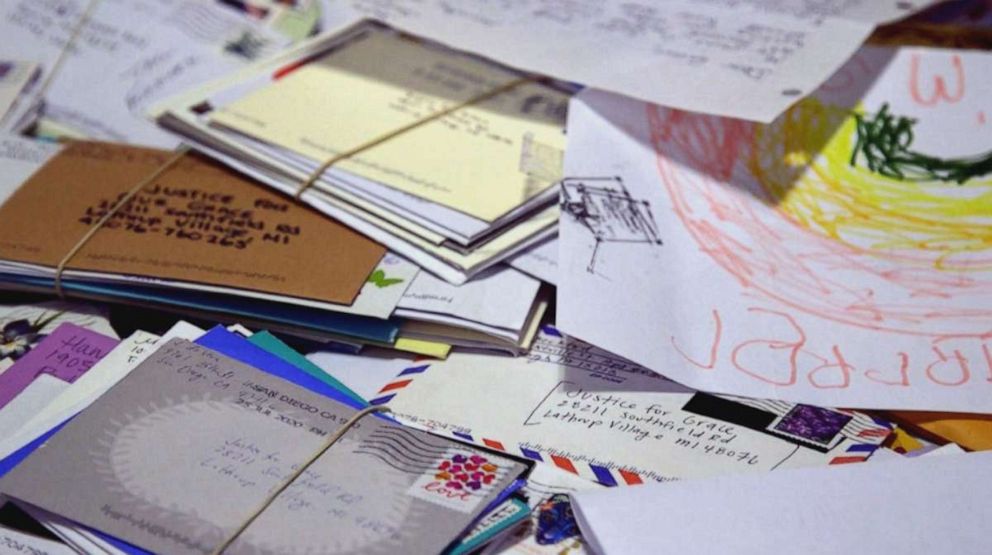

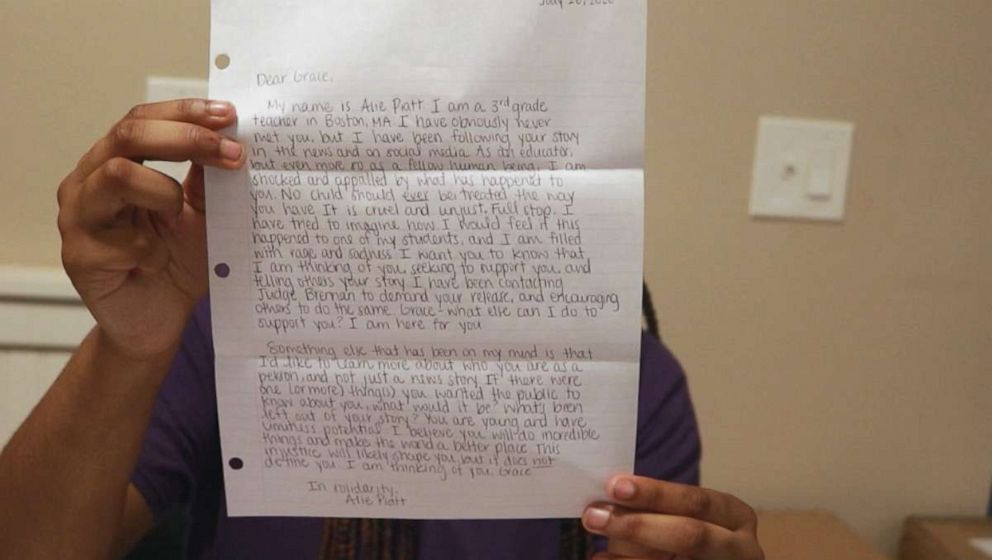

Grace still holds on to all the letters of support that she received during her time in juvenile detention, but she said one still stands out for her: The first one she sent to her mother from inside.

"Dear mommy, I miss you a lot, and being here is hard. I haven't really wrote you because I had to ask God to give me strength to do so. I couldn't write without crying or feeling bad for the rest of the day. ... Please continue to send me pictures of me and you or just with anyone. I love you, mommy, and I miss you," the letter reads in part.

Cohen said that she received a call from Charisse in May 2020. After Charisse told her about Grace's situation, "it didn't sound right," Cohen said.

"Most lawyers who looked at the case didn't think it was possible to get her out of the detention center," Biernat said. "It would be too difficult to convince the judge to change your mind."

Salma Khalil, another of Grace's lawyers, added that "these cases are long, they're drawn out, they're complicated [and] they require a lot of resources."

ProPublica published Grace's story in mid-July 2020 and it quickly sparked widespread outcry -- far more attention than Charisse had expected, she said.

"We immediately started to receive phone calls from all over the country. We got calls from senators, we got calls from legislators in [Washington], D.C. It was amazing," Biernat said.

Cohen said she didn't expect her article to trigger a social media movement calling to free Grace. High school students slept outside, near the facility in protest of Grace's incarceration. A petition for her release garnered hundreds of thousands of signatures. And a grassroots organization led a 100-car caravan from Grace's school to the detention center.

Less than a week after the ProPublica article, as pressure to revisit Grace's case mounted, Brennan agreed to a hearing on a motion to release her from detention. During the hearing, Brennan recounted Grace's history of encounters with law enforcement, which go back to when she was a preteen, Cohen said, adding that Brennan used the hearing to make her point of view on the case public.

Meanwhile, Grace pleaded with the judge for her release, saying, "Each day, I try to be a better person than I was the last, and I've been doing that even before I was in this situation. I'm getting behind in my actual school while here [at the detention center]. The schooling here is beneath my level of education."

Brennan ultimately decided that Grace belonged in juvenile detention and denied her release. Khalil said that, at the hearing, Grace and Charisse hugged in what she described as a "heartbreaking moment."

"I think people need to remember that Grace and her mom have a very close bond," Khalil said. "Charisse raised Grace with her own hands. She's an involved mom, so the trauma that they are both experiencing and being separated from one another … it just breaks your heart that our system did that to them."

Biernat, however, said they "weren't going to sleep" until she'd been let go, and filed a petition with the Michigan Court of Appeals. It worked. Eleven days after the hearing, the appeals court ordered Grace to be released immediately.

Now, nearly a year after her experience, Grace is an honors student who enjoys taking pictures during her free time. She's also started to speak out about her experience, which has begun to catalyze change in the state. In June, Whitmer signed an executive order to create a task force on juvenile justice reform.

One of the goals of Whitmer's task force is to collect statewide data on the juvenile justice system's influence on youth who enter it, including how many youth within the justice system -- regardless of their race -- are there due to school discipline or academic issues. Smith said these numbers are currently "unknown."

"There are thousands of other Graces out there and we need to pay attention to those children," Charisse said. "Our Black girls are being criminalized. My child was criminalized because of her behavior and her ADHD, but Black girls are being criminalized just because of who they are."

Attorney Allison Folmar, a longtime family friend who is now representing them, told ABC News they are now planning to file a due process complaint against the school district where Children's Village is located, alleging that Grace was denied her right to adjust to remote learning as a student with ADHD.

"The Individuals with Disabilities [in Education] Act exists because you have to prohibit the very injustice that occurred in this case," Folmar said. "This federal act empowers students who are differently abled to learn in accordance with his or her individual ability and progress. Students cannot be forced into mainstream academic practice that leaves them at an educational disadvantage."

She went on, "So, this is about making sure that the educational system does not leave another child behind and … say we're speaking of this case, to criminalize the inability to learn in this type of situation."

While she noted that Grace is "still trying to recover academically" after her time in juvenile detention, Folmar also said that Grace "excels" when given "all of the necessary tools to thrive" and pointed to her becoming an honors student.

"We are simply trying to make her whole," Folmar said.

Since her learning plan had been disrupted by her incarceration, Folmar said they're now seeking compensation in the civil case to pay for the new school she's attending as well as the services she needs to succeed academically.

Grace said that her future plans include going to college and starting a computer information or cybersecurity business. She also said she wants to continue to advocate for others.

When asked if there was anything she would say to Brennan, Grace said she would tell her, "I'm not just what was on the papers. I'm not just what you saw from those reports or what you saw in those files. I have so many different attributes and I'm so different than just that, and I hope that she doesn't judge everyone based on just that."

ABC News' Gabriella Abdul-Hakim contributed to this report.