Teachers are reinventing how Black history, anti-racism are taught in schools as system falls short

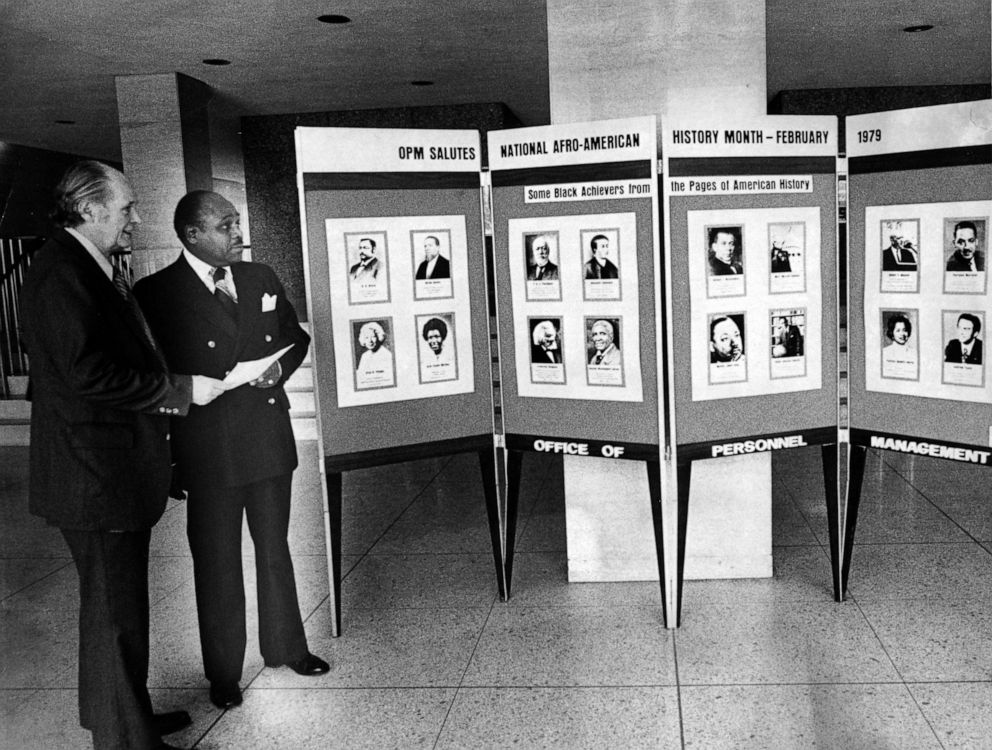

When historian Carter G. Woodson was calling for the first Negro History Week in the 1920s -- which would go on to become what we now celebrate as Black History Month -- he said of his efforts, "This crusade is much more important than the anti-lynching movement, because there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom."

Now, 100 years later, the fight to have Black history be centralized in textbooks and anti-racism be a new focus in schools has reached new heights amid protests sparked by the death of George Floyd -- the Black man who was killed at the hands of a white police officer in Minneapolis on Memorial Day.

"What people need to understand is the man, the officer, who put his knee on George Floyd's neck learned from kindergarten through fifth grade that it was okay to disregard Black people," Dyan Watson, an editor of "Teaching for Black Lives," a teaching guide that grew out of the Black Lives Matter movement, told "Good Morning America." "He learned at a very early age that he was superior to Black people."

"We can't wait until high school or until college to start teaching about these issues," she said. "[Kids] are already thinking about it and they're talking about it."

Because Floyd's death has ignited conversations on racism and how it's learned, experts argue that the history of prejudice and anti-racism should be taught within our school system. There's also the claim that textbooks are lacking a deeper dive into Black history. Should this framework exist, would hate crimes and injustice become obsolete for future generations?

How Black history is covered in schools

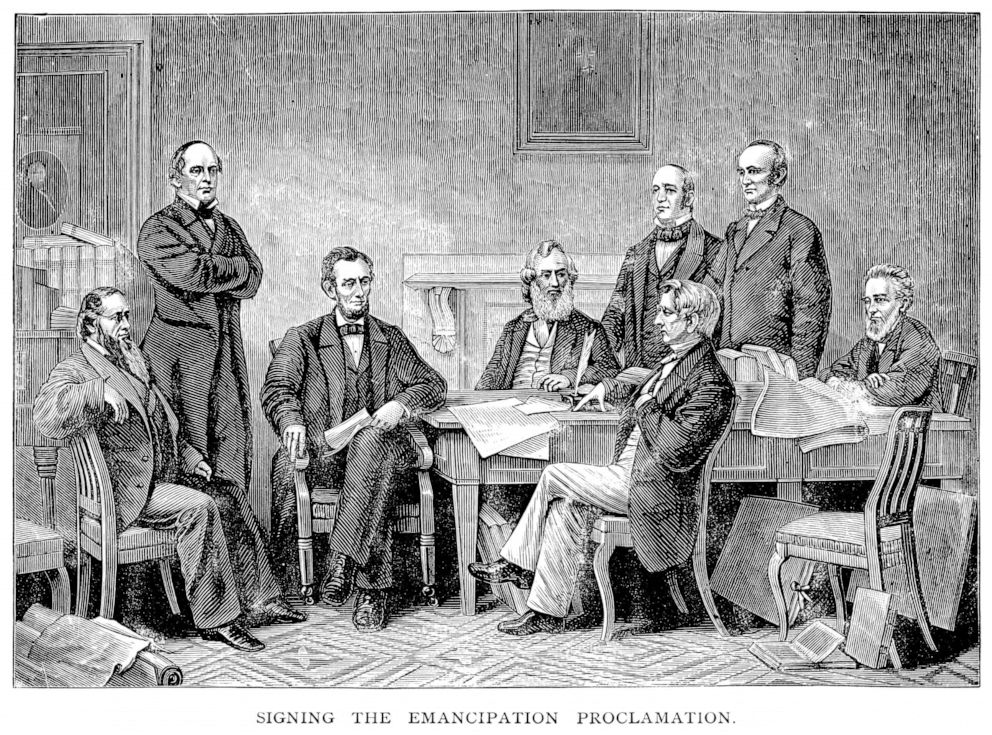

American history lessons generally teach that when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, it ended the Civil War and slavery.

Many students in the U.S. do not learn about June 19, 1865, the day that General Gordon Granger arrived with troops in Galveston, Texas, to finally end slavery there, more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect.

That day, known as Juneteenth, is considered a second Independence Day for Black people in the U.S. and has been celebrated for 155 years, though it only captured nationwide attention amid protests calling for racial justice. Many Americans had never heard of the liberation.

Black history is typically taught in schools through the prism of victimization and oppression instead of "persistence and resistance," according to Tina Heafner, president of the National Council for the Social Studies and a professor of education at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

"We know that students of color don't have anything to connect to within American history curriculum," she said. "The curriculum is presented from that of the dominant white culture and it's not inclusive of people of color."

Though slavery is taught in history classes, only 8% of high school seniors could identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, according to research conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) in 2017. And more than half of teachers found their textbooks inadequate on the topic of slavery.

From kindergarten to fourth grade Kennedy Mitchum, 22, attended a school where students were mostly Black. While in grade school, she recalls learning about a president's policies for change, along with Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and their fights for equality.

"We were taught that we live in a post-racial society," Mitchum said. "There was nothing on how racial injustices continued to happen to people. It was hard to understand what racism was until I experienced it myself as a Black woman."

Mitchum, a recent graduate of Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, was the only Black student in her middle school. When she'd get picked on or faced injustice, she didn't understand until she Googled, "discrimination of blacks."

"That's when I knew I wasn't alone," she said. "As soon as we're in the classroom learning math, history, we should be able to understand what racism is."

After Floyd's death, Mitchum, of St. Louis, Missouri, contacted Merriam-Webster, the company known for publishing dictionaries and was successful in persuading the company to alter the definition of racism, saying, "It should include racial prejudice as well as the institutional power and oppression that exists all together."

While there have been more efforts by publishers to make textbooks more inclusive and thorough, the pace of change is slow and often riddled with red tape, differing opinions and a lack of resources for schools, experts say.

Like teachers and students, textbook publishers also face the pressure of standardized testing, the focus on which condenses what students learn, according to Lawrence Paska, Ph.D., executive director of the National Council for the Social Studies.

"Very often the Black experience is reduced to things that can be tested, so we're talking about the 14th Amendment compared to the 15th or having a test question on Jim Crow laws, the Civil Rights movement and several of its key leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr.," he said.

A spokesman for McGraw Hill, one of the nation's top textbook publishers, said while the company engages a diverse range of experts to "continually refine" their materials, their work is structured "by the courses that schools teach and very much by the state standards for those courses."

"Coverage of Black or Latino history, slavery, the civil rights movement or other topics, which would commonly be covered in social studies, is strongly shaped by what the states, districts and teachers are being asked to teach through those standards," the spokesman, Tyler Reed, told "GMA."

#teachoutsidetextbook

The urgency in trying to advance what and how students are taught about Black history has motivated educators and historians to move beyond just trying to change textbooks and instead publish their own materials.

"Even if the textbooks were good, it's a bad idea for young people to learn that you can learn everything you need to know from one source," said Deborah Menkart, the executive director of Teaching for Change, a non-profit organization that offers educational resources for teachers and parents. "We do want young people to learn to be critical readers and to look at multiple sources to kind of dig into history and current events."

Teaching for Change uses the hashtag #teachoutsidetextbook to encourage educators to use resources like its Zinn Education Project, which offers articles and free lessons on history organized by grade level, theme and period in history. The project, a partnership with Rethinking Schools, another resource for teachers, is based on the history highlighted in Howard Zinn's best-selling book, "A People's History of the United States."

In the weeks following Floyd's death, the number of new teachers who have signed up to access the Project's lessons has quadrupled, according to Menkart.

"In the midst of this, there are many teachers who are really dedicated to making sure students learn the history that has been left out of textbooks," she said. "They are working against the norm though and they do often face resistance."

Resistance to teaching a more inclusive, diverse and full history of the U.S. -- one different than students' parents, administrators and teachers were taught -- can come from parents, school administrators, district officials, state officials and even teachers themselves, according to Heafner.

"The issue we have is it depends on the teacher and the support the teacher has within the school district and within the school," she said. "[Support] needs to come from the Department of Education. It needs to come from the state board of education in every state. It needs to come from the district level"

Watson's book, "Teaching for Black Lives," is a collection of writings, with accompanying teaching materials and resources, designed to help educators humanize people of color across all subjects, not just history and social studies.

"The response can't just be, 'I'm going to include more voices when I teach the Civil Rights unit,'" said Watson, an associate professor at Lewis & Clark Graduate School of Education and Counseling. "It really needs to be from September through June, how am I exploring issues of equity and social justice every day and making it a habit?"

"If I'm teaching math, how am I helping my students use these mathematical concepts to eradicate racism and injustice?," she said. "Do I highlight experts from my field from varied social locations -- race, class, gender, ability -- so that my students see themselves in those roles?"

Even if teachers are not allowed or cannot afford to have new textbooks or additional resources in their classrooms, Watson says they can teach students to question what they're learning.

"Take the textbook that you were issued and interrogate it. Ask the students, 'Whose perspective was left out? Who might see it differently? What else do we know to be true?,'" she said. "Really get students to be detectives and help them understand how to do it so... they can do it on their own."

Teaching Black history vs teaching anti-racism

Even if students are exposed to a more complete history of the U.S. that elevates the Black experience, experts say they are not learning anti-racism.

"Anti-racism has to recognize first your identity, your bias in that identity and also the ways in which your communities are affected," said Heafner. "Anti-racism instruction is helping particularly students who come from a position of privilege and power to recognize what that is, to see what it is, to understand their role in society as a result of that, to understand their experiences from that point of view."

Anti-racism education is not mandated in all schools, it is not tested on standardized tests and it does not fall under federal guidelines, but it is critical, experts say.

"Children are not born racist, so exposure to different cultures, positive role models, different ethnicities, skin color, teaching about the beauty and significance of difference is important," said Dr. Janet Taylor, a psychiatrist and the mother of four Black children.

Discussing racism in classrooms is crucial for minimizing unconscious biases in children, according to Taylor. These lessons begin with adults teaching kids how to recognize those unconscious biases so they can change that behavior.

"Because adults primarily are uncomfortable talking about racism, ethnicity or unconscious bias, so when our kids bring up differences like, 'Mommy, there's a brown girl or a Black girl.' We'll say, 'Oh, don't say that,' instead of explaining why," Taylor explained. "So, parents and teachers need to become more comfortable with talking about differences in a positive way."

"It's been up to Black people to identify racism and racist acts when they happen to them. So, it's all hands on deck," she said. "It's critical that every teacher feel equipped to look at a situation, critically, defuse it and address it."

Verjeana Jacobs, chief equity and member services officer, of the National School Boards Association (NSBA) points out, for instance, that in classrooms in the U.S., 80% of teachers are white.

"That doesn't mean that they can't teach children of color but it does mean that we have to have the greater conversations about who are the students walking into your classroom," she said. "It's one thing to put anti-racism in a curriculum. It's another thing to see how that plays out into behaviors and into communities so that everyone is lifted up in a different way going forward."

Whether the Floyd protests will spur an increase in anti-racism education in schools remains to be seen.

"There are 90,000 school board officials across the country who are going to have to make some really important decisions in the next few months," said Anna Maria Chávez, executive director and CEO of the NSBA, a federation of 49 state associations "We've heard a lot over the last few years and people now want to see concrete policy action."

What an anti-racism curriculum looks like

Before implementing an anti-racism curriculum teachers should self-reflect, according to Crystal Simmons, Ph.D., an assistant professor of social studies, international and multicultural education at SUNY Geneseo, who worries about anti-racist education becoming just a "buzzword."

"[Teachers] have to be able to look into their own biases and privileges," she said. "They have to agree to what an anti-racist framework stands for, and that's challenging and dismantling racist policies and practices and curricula and inequities that exist and permeate in our schools."

In terms of what instructional goals would look like for elementary students, Simmons suggested using children's literature to help formulate discussions. For middle and high school children, Simmons said introducing current events projects and an analysis of those news stories is a good place to start.

When Brooklyn kindergarten teacher Vera Ahiyya gives lessons to her students, it goes beyond reciting the alphabet. She also speaks openly with the 5 and 6-year-olds about what it's like to be a Black woman in America.

Ahiyya talks about a time she was followed by a sales clerk at a store, and tells the children about her grandfather, who had to watch movies outside the movie theater instead of inside with other patrons. She follows up those stories with questions like, "Why do you think that is fair or unfair? What would you do if you were told you had to watch a movie outside?"

"You can empower children with words and knowledge in a very simple way," Ahiyya explained. "They do know what it means to tell somebody, 'You can't do this,' and if you add in, 'A lot of people weren't able to do this because of their race or because of the way their skin looked,' kids can understand that and they can understand judgment and inequality."

For students of all ages, teachers and parents need to not sugarcoat America's painful relationship with race, according to Simmons. She also stresses that racism should be acknowledged as systemic instead of just viewed through individual acts.

"It's important to talk about this violence... granted, if you're talking with a younger student, do you go into much details? Maybe not," she explained. "But I don't think we should be shielding students from this. They're living history. We have been sanitizing these racial stains, these atrocities that have happened, and when we fail to acknowledge pain, oppression and this violence, it's going to continue to be very problematic for society."

Gholdy Muhammad, an associate professor of education at Georgia State University, says teachers need to not only be self-aware but also willing to include anti-racism work in all lessons. Her book, "Cultivating Genius," lays out a four-part framework for teaching equity, focused on identity development, skill development, intellectual development and criticality.

For a math lesson, for example, Muhammad said an anti-racism approach would be to talk to students about "The Green Book," a guide that grew in the 1950s and 60s to catalog Black-owned businesses across the U.S. so Black people would know where it was safe to travel.

The students would learn about identity by having to pick a city in the U.S. to travel to and what they would pack, they would learn a skill by calculating travel distances, they would learn a full history of what African Americans had to endure at that time and would learn to think critically about how things have or have not changed for Black people.

"I want our children to leave K-12 education and not contribute to wrongdoing or oppression," she said. "I don't want them to see someone and treat them badly. I also don't want them to be neutral. I don't want them to be silent on issues. Being non-racist not enough... We need anti-racism. We need people who will act."

What happens next

Schools face a difficult road ahead as they deal with both budget cuts and responding to the coronavirus pandemic, but now is the time for action, experts say.

"My hope from this is that there will be a national recognition and commitment to make sure that what children learn is treated with the same urgency as the crises that we're facing in the country and that children will have a chance to grapple with those," said Menkart. "School can be the place where children learn the information they need to make informed decisions, to learn how people have organized before, to learn to think critically about issues of race, of gender and class, citizenship, nationality and then help shape a better future for all of us."

School districts and states have already been increasing their focus on issues of "equity, culturally-responsive curriculum/teaching and social-emotional learning," according to Reed, the McGraw Hill spokesman. It is a trend he said the publishing company expects to grow.

The school officials who decide what textbooks are used and what curriculum is taught must also be held accountable, says Chavez of the National School Board Association.

"That means asking school boards to have those conversations at their school board meetings to get feedback and information from parents about what parents want to see taught as part of the curriculum in classrooms," she said. "We also are encouraging parents and individuals to run for school board positions because, again, [they] have a determining factor of what's taught in schools."

As both a parent and an educator, Watson says an "overhaul" of the curriculum in U.S. schools is "what we need."

"I am hopeful. I have to be. I have two black sons," she said. "Whenever race comes up [in school], my older son in particular just feels terrible."

"It should be a thing where there is no such thing as when race comes up," Watson said. "Everyone knows they have a race, that there are different races, that you are starting at different starting lines because of your race and we're all working to change that. That should just be a thing that everybody knows. That is not happening and it's disappointing and frustrating."