A tale of two Art Basels: The $120K banana installation to the festival's influence on local Miami communities

Art Basel draws over 70,000 visitors every year to the heart of Miami Beach for four days to enjoy a wide array of the best modern art the world has to offer. It's helped usher in a cultural revolution in Miami.

Focused on contemporary art, Basel has become known all over the country not just for some of the most sought-after pieces in the world but also for its ability to go viral. This year, it was an installation featuring a banana duct taped to a wall that sold for $120,000.

But for an event that's gained so much traction and international popularity, it begs the question: Is Art Basel highlighting a robust international art scene or burying the one that made this city great?

The answer to that question depends on who you ask. In this tale of two Basels, one is marked by tourists, high price tags and national headlines, while the other is authentically and unapologetically an experience of Miami and the people who live there.

On the floor of the Miami Beach Convention Center, longtime Miami resident and gallery owner Fred Snitzer is pleased with his success at the festival.

This year, he featured the works of internationally renowned and locally born artist Hernan Bas.

"This year for the first time we decided to do a solo exhibition with him. And so all of this work, this entire body of work, was painted for this exhibition in the fair," Snitzer said.

A member of Art Basel's selection committee since its inaugural event in 2002, Snitzer has seen the impact the event has had on the city.

"Art Basel has made a profound impact on this community. Real estate values, the cultural life of Miami," he said. "There's much more support for the museums because the community started to understand the scope of the visual art world, the value of a cultural community; that it wasn't the only reason for an area to thrive."

"You could move to Miami because you're interested in culture. Miami is filled with culture," he added. "There's so many different cross sections of people that live here and come here and affect the community and they're here and it is super viable."

But a few rows down, a different exhibit is ripe with attraction: Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan's installation of banana duct taped to a wall, which is coyly titled "Comedian."

A line of eager visitors to "Comedian" waited in a line that passed through other exhibits, and there was increased security and police presence. The facetious piece was easily the story of the weekend with its lofty price tag, but White Cube, the London-based gallery next door, didn't really seem to mind.

"I think Maurizio Cattelan is a really important artist. I think a work like this really challenges people to really think about what is art, what does it mean and he's really playing with the audience," said Leila Alexander, White Cube's director. "So it's exciting, actually, to see the response to it, and it has been gathering crowds every single day. So it's good just to push the conversation of what art can be."

"It's a good atmosphere for the fair. We enjoy it. We just want as many people to come to fair as possible," Alexander added.

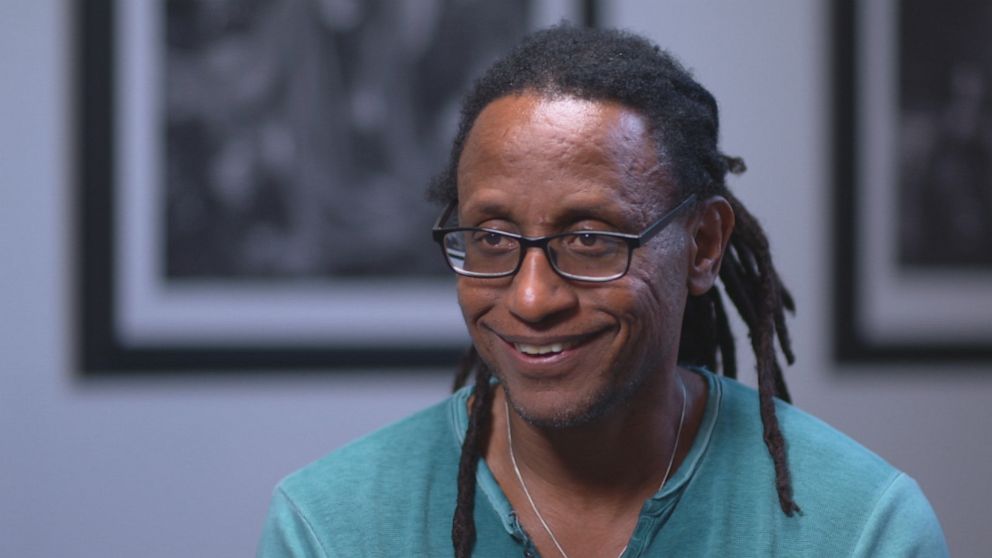

While Basel-goers were able to have fun with the statement installation by Cattelan, less than 7 miles across the causeway, in Little Haiti, Miami Herald photographer Carl Juste isn't laughing.

"You want to talk to me about bananas? Well, I think that's a diversion," Juste told "Nightline." "People like me cannot afford [that]… I'm an immigrant. I'm an American. I got a lot of living to do it. Bananas [are] not gonna cut it."

Juste wants to make sure the immigrant communities beyond South Beach aren't forgotten. He says they are integral to the creative fabric that has come to define Miami.

In the heart of Little Haiti, Viter Juste, Carl Juste's father, is immortalized in an immense mural honoring him as one of the founding fathers of the neighborhood.

"This mural kind of represents…little Haiti [and] all its prominent, various individuals that really fought...not only for the name but for the identity of this immigrant community," Juste said. "Tourists come here and they take an image or selfie. So this is our meeting point. This is a welcoming mat for tourists and visitors."

"It's right across the street from my office as you see, every morning I come by and I just look at my dad and I said, 'I'm doing it right,'" Juste added.

Juste said he first found art through his father.

"My dad had painting… He sold music. He sold literature," he said, adding that his father would bring Haitian musicians to Miami to perform. "So I would see the performances in his store. There'd be books… My dad had reggae, salsa, merengue, bachata. It was always around me."

His lifelong interest in the arts directly translated into his studio space in the neighborhood, which he uses to promote local artists and projects related to Afro-Caribbean heritage.

Juste said that when Art Basel came to Miami in 2002, he had no expectations.

"I was not part of it. Nobody looked like me the first time I saw Basel," he said.

Back then, Little Haiti was a lot bigger. But with increased development across the city, the claws of gentrification have crept in.

"The walls are definitely closing in. Little Haiti was from 36th street to the south, 82nd street to the north… Now it is…eight blocks," he said. "As you can hear…Creole Christmas songs… How sad would that be when that's gone?"

In that eight-block radius, notes of Creole culture are everywhere.

"It's what my mom cooked," Juste said of the food in the neighborhood. "It's like memories on your tongue. You bite into a meat, you bite into a rice, or to a banan pezze, and all of a sudden you're transported back home."

"As a kid, it was wonderful running in the rain. Seeing palm trees, eating mangoes, jumping in people's pools of the playground, every one of us. That was my playground," he said. "I…credit my parents for that because they developed a community in which I can identify people who look like me. Regardless what the media was saying at the time."

In 1980, Haitian immigration in the U.S. reached a peak when 25,000 asylum seekers arrived in South Florida during the Mariel boatlift. It's when Little Haiti became the heart of the Haitian diaspora.

"Was this something that has been imported to Haiti?" he said of the artistic culture in the neighborhood. "Art is what was exported."

"This [is a] fallacy that we lived in a vacuum…[and] now we're civilized. We've been civilized for a long time," he said. "Because we have something to say, because we understand the various struggles...both in our homelands and living in this great country. And what better source of art than life itself?"

Juste believes the $120,000 banana installation is "perverse… You can laugh at that."

"Maybe somebody may see it as a joke. I don't take it as a joke… This is about identity. This is about a sense of equality. So you're going to say my dignity is less than a banana on the wall," he said. "You'll never see bananas on a wall in Little Haiti… You're never going to see that because we paid too much of a price to be here."

World-renowned Haitian artist Edouard Duval-Carrié has partnered with Juste to defend Little Haiti.

"They've lost a lot of neighborhoods...already. And let's not lose this one," Duval-Carrié said. "We've seen the neighborhood change so fast. So that we're trying to really maintain, the Haitian presence here and trying to elevate the discourse as well concerning that."

During Basel, Duval-Carrié's art hangs in free galleries throughout Little Haiti, surrounded by other Caribbean artists.

"This is the real thing. This is the purity of the Haitian American experience. This is the essence of the immigrant story," Juste said.

Back over the bridge, on South Beach, public art projects commissioned by the city of Miami Beach have created an enormous display of cars in a traffic jam made entirely of sand along the iconic shore.

"It was money well spent. All day long, people are coming here... People from all walks of life, all socioeconomic levels, all nationalities, with their kids, sharing this experience and taking in from this piece of art what they believe it means to them," Mayor Dan Gelber told "Nightline."

For better or for worse, injecting an event like Basel into Miami's bloodstream undeniably changes the city in big ways. But that's not to say the residents necessarily mind. It's a question of culture and ownership. They just want to make sure it's theirs that's being shared.

Juste curated a show in Little Haiti sanctioned by Art Basel, "and that's a first," he said.

"We take we take a huge pride in that. It's important that this is the new Miami. Basel 2002 is a segregated Miami. The Basel 2019 is the complete Miami," Juste said. "Remember you have to be the change that you want. This is our attempt to make that change happen. Moving forward in 2019, Miami has changed."