Surgeon who treated Roy Horn of 'Siegfried and Roy' after tiger incident says 'he actually flatlined…we lost vital signs'

When Dr. Allan MacIntyre got word that a man who had been bitten by a tiger was being brought in to his Las Vegas hospital on Oct. 3, 2003, he said he wasn’t sure what he was in for at first.

“They don't tell you that they're bringing in a celebrity,” said MacIntyre, a general surgeon at University Medical Center. “They say we have…male patient that has been bitten by a tiger in respiratory distress. They'll say it's a Class One activation, which means everybody presents to the trauma bay.”

He soon found out the patient was Roy Horn, one of the legendary entertainers behind the famous “Siegfried and Roy” shows, who had been bitten by his white tiger, Mantecore, during a performance.

Watch the full story on the season premiere of "20/20" FRIDAY, Sept. 27 at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

When Horn arrived at the hospital’s level I trauma center, doctors quickly determined he had suffered major puncture wounds to his neck.

“A tiger bite to the neck… We don’t see that on a daily basis like a gunshot wound, so you have no idea what to expect,” MacIntyre said.

The tiger’s teeth had gone in deep enough to damage enough blood vessels, causing serious internal bleeding, MacIntyre said, and the injuries “compromised Horn’s airway.”

“You’ve got to deal with that first,” MacIntyre said. “If you’re not breathing for over, like, three minutes, you will have irreversible brain death.”

Horn was rushed into emergency surgery.

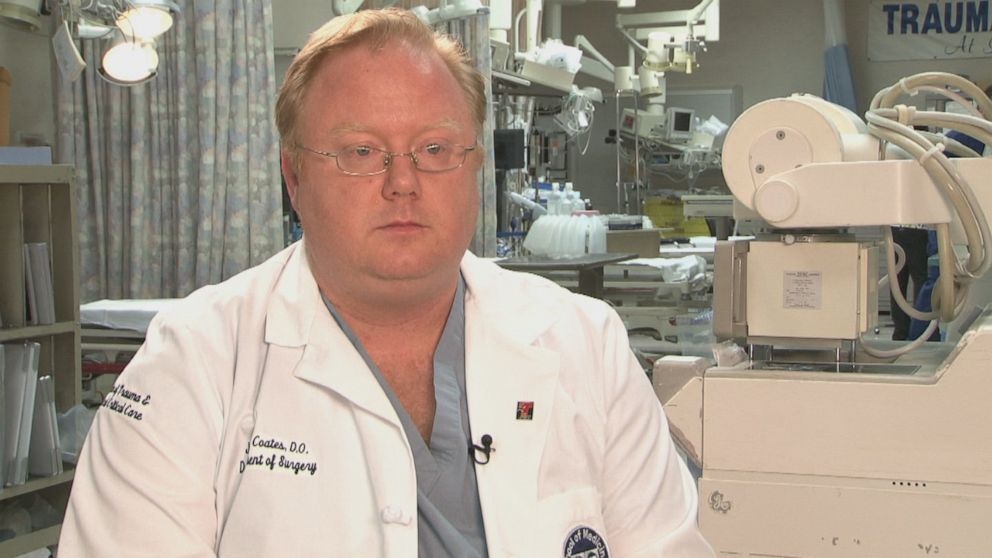

Dr. Jay Coates, a trauma surgeon at UMC who operated on Horn, said, “We had to operate on his neck where the wounds were at and control the bleeding.”

The two doctors said Horn even died -- at least once -- before they revived him.

“Roy was in such distress from his airway -- loss of airway -- that his heart stopped multiple times,” MacIntyre said.

“He actually flatlined...or died,” Coates added. “We lost vital signs on him.”

Coates said that Horn left the hospital about a month after he was admitted. He said Horn “was with it enough to communicate with us, [but] he was still on a respirator intermittently.”

MacIntyre added that this was where the “real journey” began for the entertainer.

“You have to literally go back to, like, when you were an infant, and learn how to walk again, and how to talk again and how to swallow, and [Horn’s] drive, I believe, is what got him through this,” MacIntyre said.

Doctors were able to save Horn’s life, and he eventually made a remarkable recovery, but he had suffered a stroke, though when the stroke happened, and what caused the tiger to bite Horn, has been questioned.

A relationship built on trust

By all accounts, the Vegas entertainers should have had their last performance on Oct. 3, 2003.

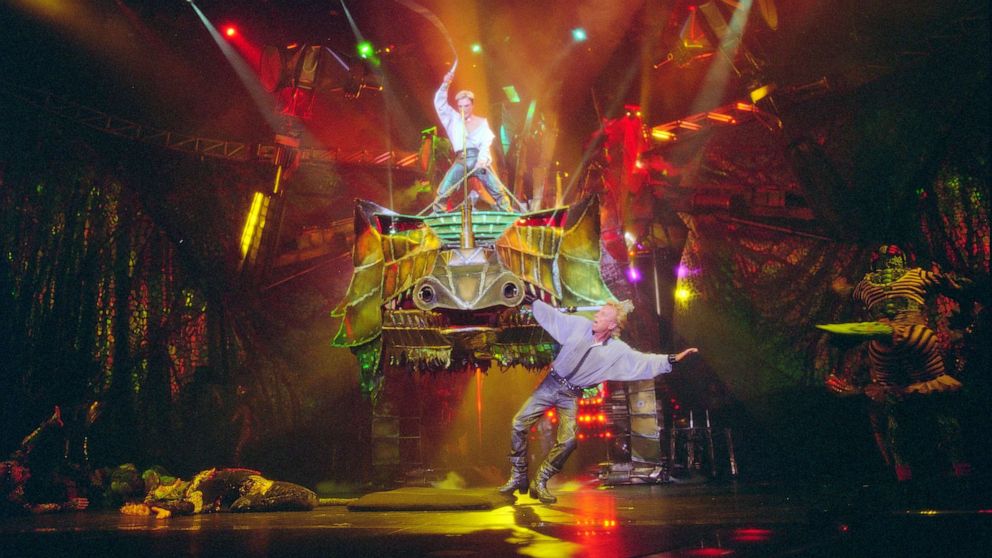

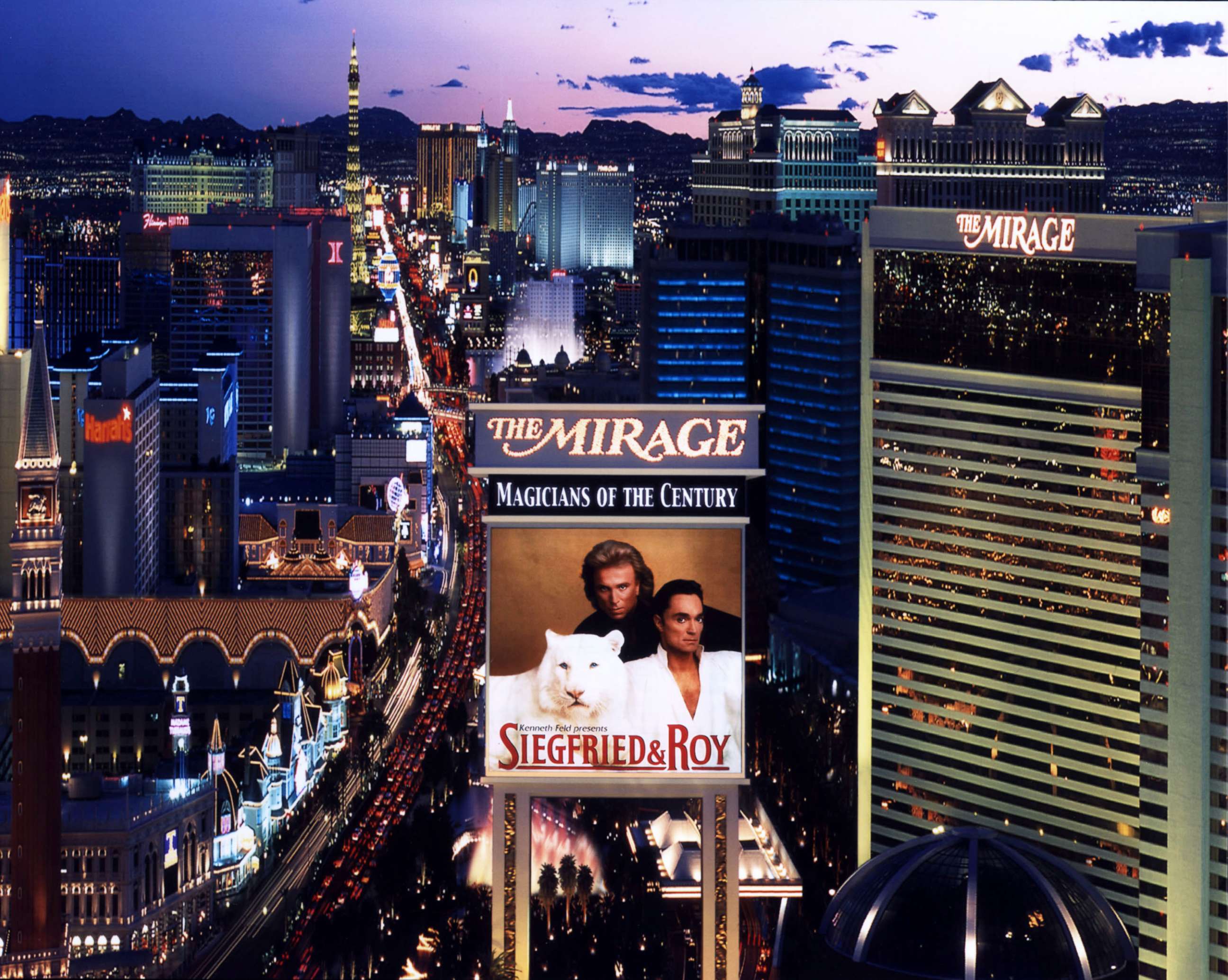

The German duo Siegfried Fischbacher and Roy Horn were a smashing success on the Las Vegas Strip at The Mirage hotel and had become one of the top-grossing acts on the Strip. They were masters of magic who shared a stage with some of the rarest and most beautiful animals, including white lions and tigers.

Mantecore had long been a fixture in “Siegfried and Roy” shows. Appearing in the last half-hour, Mantecore would be led out by Horn on a leash to walk onstage.

Lynette Chappell, one of the duo’s closest collaborators who had worked with the pair since the 1970s, was part of the 2003 show when the incident happened.

“He would turn [Mantecore] around. [Mantecore] would be seated, and then...Roy would give the command and Mantecore would react to the command and rise up,” Chappell said. “Then, Roy would exit and go upstage with Mantecore.”

Horn had performed the same act with Mantecore thousands of times, Fischbacher said. In their 30-plus years of performing with animals, Fischbacher told “20/20” in the pair’s exclusive interview that there had been no major incidents -- only some “minor mishaps” with their animals -- until that day in 2003.

"[There was] only that one [major incident]. And that was an accident," Fischbacher said.

For example, a black jaguar once popped out of a trunk onstage and its chain had broken. Another time, a tiger named Sarah jumped out from a bush in the garden of their jungle-like Las Vegas compound and pinned Horn to the floor. Horn bit her on the nose to make her release him.“She is going by pure of her instinct [sic],” Horn said in a 1996 ABC News interview. “Well, I went by pure of my instinct, what another cat will do in the wild. … So I pull her [in] and then I bit her on the nose. She was startled.”

Horn said that Sarah got up, walked away and looked at him, after which he signaled to her that everything was OK.

“They are simple-minded,” he said, comparing them to 6- or 7-year-old children with hundreds of pounds of power. “So you can’t argue. You cannot, with force, get them to do anything they don’t want to do. You analyze what they’re doing the best, what is their personality, so you never put them in a situation they wouldn’t like to do.”

To build trust with his cats, Horn would train them essentially from birth, he said.

“The first voice they hear, it’s mine,” Horn said in a previous interview. “The first face they see is mine. So most probably they think I am a tiger. I’m sort of their father figure. I guide them through their childhood. I let them know what’s right and what’s wrong, [and learn] the way they’re comfortable. They’re looking for me as sort of a security blanket.”

What caused the tiger to grab Horn?

Horn said during that October 2003 show, he felt dizzy on stage, then tripped and fell. Then, Horn said, he saw his 400-pound, 7-foot-long white Bengal tiger named Mantecore standing over him.

"Mantecore went on top of him, and he looked around," Fischbacher recalled of the tiger, who he said appeared to not understand what was happening.

The tiger grabbed Horn by the neck and dragged him toward his cage offstage because, according to Horn and Fischbacher, the tiger was trying to protect Horn, not attack him, after he fell, which they said was the result of a stroke.

Stagehands were stunned by what was happening and rushed to try to help.

“Mantecore was carrying Roy, heading toward his cage,” said Curtis Rowe, an electrician and stagehand who worked on the show. “I grabbed him by the tail, which caused Mantecore to stop… He’s like halfway in his cage now and he still had a hold of Roy by the neck.”

They grabbed a fire extinguisher and fired it at the tiger, which they said caused Mantecore to drop Horn. They then rushed to Horn’s aid as he lay bleeding profusely on the floor.

“We didn’t really know what to do other than just put pressure on those wounds, you know?” Rowe said. “He had seconds to live. … All we can do is wait for paramedics.”

However, Chris Lawrence, one of the trainers who was working the show that night, disputes Horn’s account of why he fell. He gave his version to The Hollywood Reporter in March saying that the tiger had missed his mark on stage during the performance and then Horn’s actions right after that caused the act to go awry.

Lawrence, who said he was in the wings when the incident happened, said in a statement that, "instead of [Horn’s] walking Mantecore in a circle, as is usually done, he just used his arm to steer him right back into his body… By Roy not following the correct procedure, it fed into confusion and rebellion."

Fischbacher maintained that Horn had fallen as the result of the stroke, then Mantecore came over and was "of course" just trying to help him offstage. Fischbacher said he had "no idea" why Lawrence came forward in March with a different version of the incident, adding, "He had problems with his life anyway."

The only video of the incident was taken by cameras in The Mirage, and it has never been publicly released.

‘Siegfried and Roy’ returns to the stage

After the incident, the ‘Siegfried and Roy’ show was shut down.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees animal welfare, investigated the incident, but in the end, it was unable to officially determine a cause for it. The USDA also did not determine whether Horn had suffered a stroke before or after the tiger grabbed him, according to David Neal, a senior investigator on the case.

As Horn recovered, Fischbacher was dealing with his own emotional struggles.

“Both Siegfried and Roy were wounded in this accident. It was very, very difficult for Siegfried. He lost part of his soul then too,” Chappell said. “Without Roy’s influence, Siegfried didn’t know what path he was on.”

Horn still loved his animals and eventually returned to the Las Vegas compound to be with them, saying that his time with them was rehabilitation for both his emotional and physical being.

“When Roy started to recover, he took Siegfried along with him, and in doing so, Siegfried started to give Roy the support, and as you see them now, they walk next to each other,” Chappell said. “Siegfried supports Roy. Roy supports Siegfried.”

For a while, the pair focused on regaining their health. They participated in a project with DreamWorks called “Father of the Pride,” a racy comedy show that premiered in 2004 on NBC in which John Goodman and Cheryl Hines voiced computer-animated versions of the “Siegfried and Roy” animals. But the TV show failed after one season.

Deciding to return to the stage one final time, Fischbacher and Horn said they didn’t just want to perform, but also give back.

On March 1, 2009, Fischbacher and Horn held a benefit show for the Cleveland Clinic’s Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas. They raised $14 million, Fischbacher said. He added that the choice to work with the Lou Ruvo Center was deliberate because the center is devoted to brain injury research and focuses on supporting caregivers.

On the night of the show, Fischbacher and Horn said they once again brought out Mantecore and performed a short series of magic tricks. On the feeling of getting back on stage again, Horn said he was “speechless.”

“It was unbelievable,” Fischbacher added. “I can’t say...how I felt. I just thought, ‘This is for the audience.’”

They also are now working on a biopic with German filmmakers Nico Hofmann and Bully Herbig that they will expand into a multi-part docuseries for television.

ABC News' Tom Berman, Jen Joseph and Rachel Wenzlaff contributed to this report.