Supreme Court's dramatic rightward turn may undermine its political distance: Experts

This story is part of the ABC News series "Democracy in Peril," which examines the inflection point the country faces after the Jan. 6 attacks and ahead of the 2022 election.

On June 24, the Supreme Court's smallest-possible majority struck down the long-standing Roe v. Wade ruling, which had for five decades guaranteed a right to access abortion. It was a rare instance of the court -- whose transformative power on society stretches back to the early 19th century -- restricting rights it had previously extended via the Constitution.

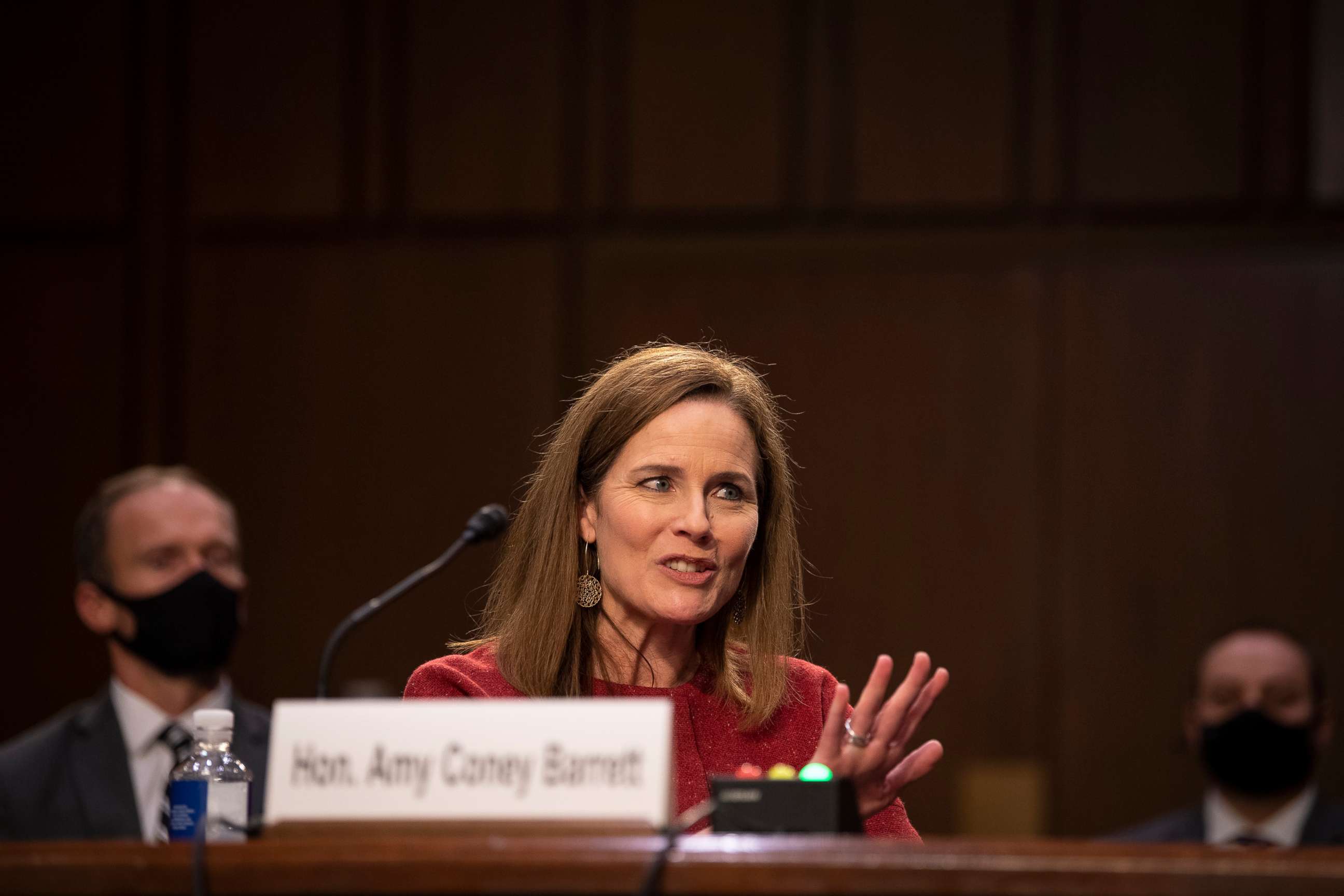

Roe's reversal was partly possible because of the votes of the court's three most recent justices, all of whom were appointed for life by President Donald Trump -- himself elected by a minority of the population though he lost the popular vote -- and confirmed by Senate Republicans representing roughly 43% of the country.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who has helmed the court for 17 years after being appointed by George W. Bush and has emerged as a swing voter, lamented the court's landmark opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization as going too far, too fast, and the ruling touched off instant, passionate reactions from both sides.

The ruling also brought renewed attention to the Supreme Court's insulated role in government; its power to review and upend legislative and executive action; and the anti-majoritarian makeup of its members.

While there have been many far-reaching and consequential decisions by the high court and accusations on both sides of politicization, especially in recent decades, critics argue that the Supreme Court's current trajectory is running outside the American mainstream.

"They have burned whatever legitimacy they may still have had ... They just took the last of it and set a torch to it with the Roe v. Wade opinion," Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren, of Massachusetts, told ABC News on "This Week" in June.

But some experts interviewed by ABC News said the court is doing what it is supposed to do -- operating detached from the pull of public opinion -- even when that is deeply polarizing.

"I don't think most people would want judges or justices making decisions based on what's politically expedient, or politically popular. That's what the legislative branch of government is supposed to do," said Jared Carter, a professor of constitutional law and director of Cornell's First Amendment Clinic.

Is the court out of touch with most of the country?

While Justice Samuel Alito wrote in the majority opinion in Dobbs that Roe "has remained bitterly divisive for the past half century," an ABC News/Washington Post poll completed in May shows that 58% of Americans believe abortions should be legal in all or most cases.

Striking down Roe then inherently undermined the will of the majority, Harry Litman, a former U.S. attorney and a constitutional law lecturer at the University of California, told ABC News.

It is not the only issue on which the court and the public have split.

In a decades-long study comprised of three surveys, two researchers from Stanford University and the University of Texas looked at Americans' views on issues before the court and compared them to decisions issued by the court.

The study found a gap between the court and the public that has grown since 2020, with the court's position shifting "significantly to the right," study co-author Stephen Jessee, an associate professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin, told ABC News in an interview.

The study, published in June, found the justices moved to a position that is more conservative on all issues than an estimated 75% of the public.

"Our best estimate is that the court has almost exactly the position of the average Republican-identifying American," Jessee said.

"I wouldn't say our finding necessarily points to the court doing something wrong so much as it's just important to assess how the public's views compared to the performance of the court," he added.

According to Jessee, not every case that the Supreme Court decides favors the conservative viewpoint. Despite the politics of the presidents who appoint the justices, their ideologies don't always map neatly onto the spectrum of Democrats to Republicans. Indeed, a majority of Supreme Court rulings in the term that ended last summer -- many of them not on major social or political issues -- were unanimous or with only one dissent.

"There have been cases, for example in Bostock v. Clayton County, in which conservative justices have voted for things like protections for gay and transgender employees against employment discrimination," Jessee said.

It was a Republican-appointed justice who wrote the majority opinion in Roe just as it was the Trump-appointed Gorsuch and the Bush-appointed Roberts who provided crucial support for the majority in Bostock. Before that, Roberts narrowly upheld the Affordable Care Act, the signature domestic achievement of Democrat Barack Obama.

Roberts, the chief justice, has long taken pains to insist the court is not a partisan force and does its best to adhere to its interpretation of the Constitution. While he has been a key vote for some seismic decisions -- most notably the Citizens United ruling undoing campaign finance restrictions and Shelby County, which removed key provisions in the Voting Rights Act -- on other major cases he has counseled an incremental approach to avoid swings beyond what society might tolerate.

His view does not always win out, though, as was seen last week in the Dobbs decision.

'Greatest function is protecting rights'

While the court's recent history shows it moving rightward, according to the Stanford University and the University of Texas study, it has of course used its same power to advance other goals in the past -- drawing fierce condemnation from different groups in America.

"The framers, for all their faults, designed the U.S. Supreme Court to be insulated from political whims of the day, as much as is humanly possible," said Carter, the constitutional law professor.

Litman, the lecturer and former federal prosecutor, agreed and said the court's "greatest function is protecting rights set out under the Constitution as against efforts by a majority, say the legislature, to abridge them."

He pointed to the civil rights era of the 20th century, when the Supreme Court found through its rulings that the Constitution extended equality under the law to Black Americans nationwide, including in the Jim Crow South -- leading to pitched battles there over school desegregation and more.

But as the court's membership shifted, so too has its approach to what rights the Constitution does and does not provide versus what states can and cannot regulate.

Litman said there were other cases that have provided Americans with protections for unenumerated rights, which are freedoms not explicitly written in the Constitution, that cannot be distinguished from Roe. Many of those decisions were fiercely criticized by conservatives who said they stretched the boundaries of the court's ability. The late Justice Antonin Scalia summarized this view in dissenting from the 2015 ruling that granted the right to same-sex marriage:

"This practice of constitutional revision by an unelected committee of nine, always accompanied (as it is today) by extravagant praise of liberty, robs the People of the most important liberty they asserted in the Declaration of Independence and won in the Revolution of 1776: the freedom to govern themselves."

Scalia was in the minority then. But three of the justices on the court have changed since, all of them replaced by President Trump and all three of whom went on to overrule Roe.

The opinion in the Dobbs case threatens other unenumerated rights, Litman said -- a possibility suggested by Justice Clarence Thomas' opinion concurring with the majority in which he wrote that the court should turn its attention to overruling the case on same-sex marriage and the guarantee to contraception, among others.

"What's really wrong with the [majority] opinion, for lawyers, is it sort of pretends that there's something special or different about abortion in legal doctrine, when there isn't," Litman said.

What is to come

Carter said overturning federal protections for abortion could pose a risk to the esteem of the court, which has broader implications.

"The Supreme Court has no way to enforce its own decisions," he said. "It's just its credibility and our society's acceptance, whether we agree or disagree with the ruling of the court, that that is the law of the land."

He also said the court's current position highlights the importance of elections and of people voting; Republicans were able to appoint three justices in four years because they had the number of seats in Congress and a president in power which allowed them to do so. By contrast, President Obama could not move forward with his final nominee, Merrick Garland, because of the Republican majority controlling the Senate.

Carter said the solution is not to "tear up" the court -- rather, those who disagree with its interpretation of the Constitution should organize, litigate or challenge its decisions.

Other suggested changes include changing how long justices remain on the court -- via term limits rather than a lifetime -- or appointing more justices to the court.

Jessee, who has been studying the ideology of the court's decisions, said there are worries that recent polling indicates trust and approval in the court have decreased.

"The court doesn't have the power of the purse, and they don't have an army," Jessee said, "and therefore they sort of rely on the respect and prestige of the court in order to have their decisions followed."

"When that disappears," Carter said, "then I think we are in real trouble."