Family's abortion story sheds light on stakes of Supreme Court ruling

When Louisiana native Kim O'Brien decided to have an abortion in 2011 because her pregnancy had severe complications, she was unaware of the difficulties she would face -- including traveling to another state -- to get the care she is legally entitled to through Roe v. Wade.

Now, nine years later, O'Brien, 43, is part of an abortion case before the U.S. Supreme Court that has the potential to dramatically change the landscape of abortion access across the United States, particularly in Louisiana, where the case originates.

The Supreme Court is expected to rule on the case, June Medical Services vs. Russo, this month.

O'Brien, now a mom to two daughters, decided to tell her story publicly and join the case as an amicus curiae, or "friend of the court," because she does not want any women, including her daughters, to be denied medical care, specifically access to abortions, because of where they live or the resources they do or do not have.

"My experience was really eye-opening that women all over the place are having to comply with all these unnecessary restrictions," O'Brien told "Good Morning America." "And a lot of them probably ultimately don't get their abortion because they don't have the privileges, the financial support, the capabilities that I did."

O'Brien's experience seeking an abortion after a devastating ultrasound taken at 20 weeks was made more difficult -- logistically, financially and emotionally -- because of the patchwork of state laws like the one the Supreme Court is reviewing, called targeted restrictions on abortion providers, or TRAP laws, by abortion rights advocates. Rather than overarching bans, which often get stopped by courts, these seemingly more minor laws work to limit abortion access in reality in a variety of ways.

"It makes me really sad and really frustrated," she said. "And I feel empowered to do all that I can to try to make things better for them."

A 'perfect storm' that changed abortion access

The case of June Medical Services v. Russo centers on a 2014 Louisiana state law requiring doctors who perform abortions to have admitting privileges with a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic, which allows a patient to go to that hospital should urgent care be required.

If the law is upheld by the Supreme Court, Louisiana, a state of more than 4.6 million people whose population is 51% female, would likely go from having three abortion clinics in the state down to one, according to Kathaleen Pittman, administrator of the Hope Medical Group for Women in Shreveport, Louisiana, the lead plaintiff in the case.

The state would likely have just one physician with admitting privileges who could perform abortions, she told "GMA."

"When we decided to challenge the law, we really had no other option. It was that or shut down," said Pittman, who has worked at Hope for nearly three decades. "There is no exaggeration when I tell you that this is a really critical decision that's about to be handed down."

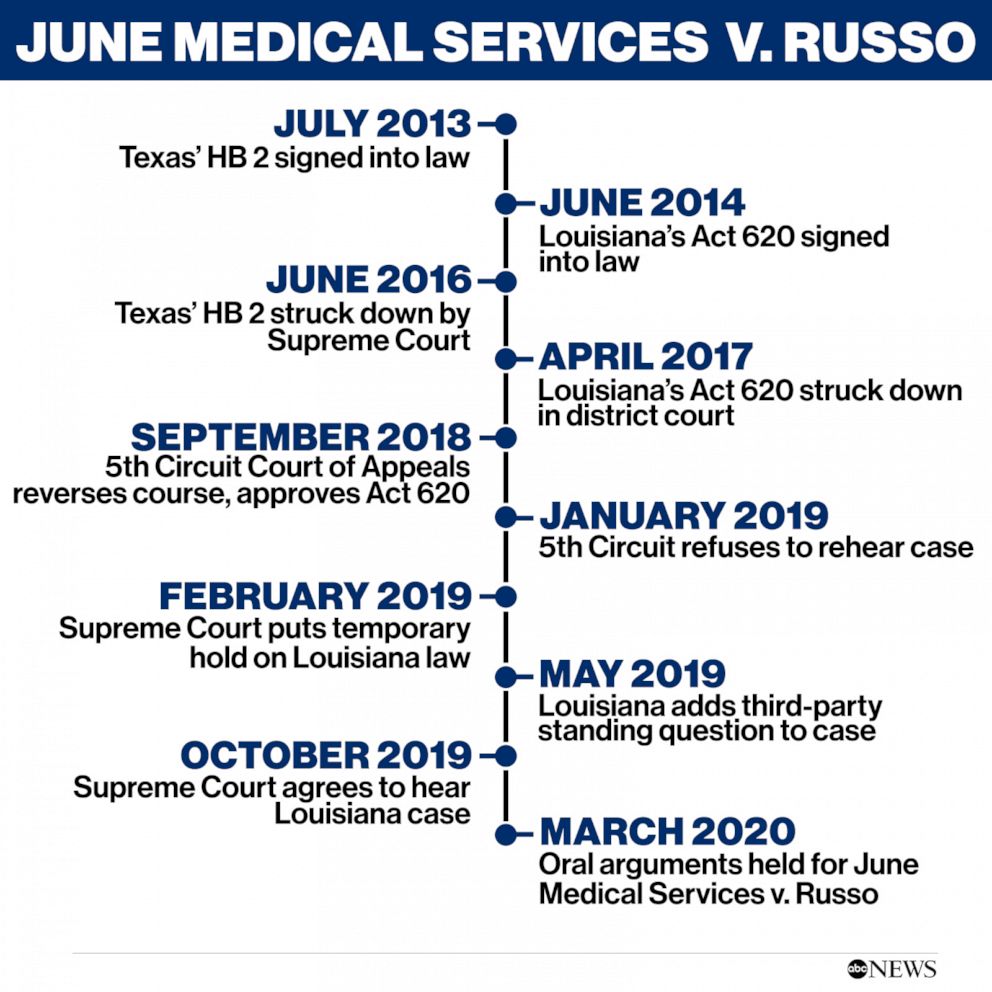

The Louisiana law behind the case of June Medical Services v. Russo is similar to a law in Texas that was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2016 -- indeed, in 2017, a federal judge struck it down on the basis on the 2016 Supreme Court decision.

In that 5-3 decision, the Supreme Court majority said the law, which required doctors to have admitting privileges at local hospitals and also mandated that abortion clinics meet state requirements for licensed surgical centers, created an "undue burden" on patients seeking access to abortion.

"When the law passed, we went from 44 clinics in 2013 down to six when the law was fully enforced throughout the state," said Amy Hagstrom Miller, chief executive of Whole Woman's Health, the Texas-based health organization that challenged the law. "It just created this perfect storm that really crumbled the fabric of access to abortion services that had existed prior to its passing."

Despite the Supreme Court's decision, the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that Louisiana's 2014 law is substantively different from the Texas measure and should be upheld because it does not "impose a substantial burden on a large fraction of women" in the state. The Supreme Court is reviewing that decision.

Even though abortion rights advocates gained a victory in the 2016 Supreme Court ruling on the Texas law, the limited time the law was in effect still managed to decimate access to abortion care for people in the state, according to Hagstrom Miller.

"Many clinics had to close, or let their lease go, or couldn't pay their mortgage, or their doctors and staffs all got different jobs," she said of the effect of the three-year legal battle. "The win was a super strong win on paper, but it came three years after the law went into effect such that it was remarkably difficult for clinics to reopen -- or new clinics to start."

Hagstrom Miller estimates there are now less than two dozen abortion clinics in Texas, a state with a population of nearly 29 million that is 50% female. By comparison, the state of Massachusetts, with a population of nearly seven million, had 47 facilities providing abortion as of 2017, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

"One of the things I've seen is we have a generation of people now who have come to just expect restrictions on abortions," she said. "They expect that there's going to be multiple delays in a waiting period and all these hoops to jump through in order to get an abortion."

In Louisiana, a 24-hour waiting period is also legally required for patients seeking an abortion, meaning they must make two trips to an abortion provider, which is often hours away from their home due to the shrinking number of clinics. Each visit can last as long as five hours, according to Pittman.

"On day one, we are required by law to perform an ultrasound ... and the stenographer goes into great detail about what he or she is seeing on the screen as far as fetal development," she said, adding that, because of state law, the ultrasound screen must be facing the patient with the sound on. "From the ultrasound, they spend one-on-one time with the patient advocate, and from there they spend time one-on-one with a physician who goes again through the process, explaining it in great detail."

Louisiana also requires parental consent for minors seeking an abortion, does not allow the use of telemedicine to administer medication abortion, and allows abortions to be performed at 20 weeks or more postfertilization "only in cases of life or severely compromised physical health, or lethal fetal anomaly," according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research group that supports abortion rights.

Both Miller and Pittman worry that if the Supreme Court reverses course and votes to uphold the Louisiana law in June Medical Services vs. Russo, it will mobilize other state legislatures, including Texas, to put more abortion restrictions in place.

In 2019 alone, more than 350 pieces of legislation restricting abortions were introduced across the country, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

"Every time a barrier to abortion is successfully implemented in one state, another state follows," said Pittman. "If we don't have an absolute win this time, we're going to see a lot of activity from other states trying to get cases before the Supreme Court as well."

What admitting privileges mean

At the heart of June Medical Services vs. Russo is a debate over admitting privileges, which a hospital may grant to doctors to allow them to admit patients to that hospital and provide medical services there.

All doctors are licensed in Louisiana through a separate process to ensure competency and safety.

Whether a hospital decides to grant admitting privileges to a doctor is a subjective process that is often reduced to numbers and whether the doctor will bring in enough revenue, i.e. patients, to the hospital to make it worth it. Hospitals can also deny admitting privileges if they do not want the doctor's specialty, i.e. abortion care, at their hospital.

Because abortion statistically has very low complication rates, the need for hospital care is extremely rare.

At Hope Medical Group for Women in Shreveport, there have been just four or five direct transfers to a hospital in the last 25 years, according to Pittman.

"That record stands for itself," she said, noting that only one of the clinic's two physicians currently has admitting privileges and the other has not been able to get them.

Dr. Pooja Mehta, an OBGYN in Louisiana and fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, calls requiring admitting privileges for abortion care an "added step that is not necessary for good care."

"Abortion care doesn't require a hospital to be safe," she told "GMA." "If you are the one in 1,000 case where that abortion may need to be watched more closely in a hospital, that abortion provider can still send someone to an emergency room and that person will still be seen in a hospital."

"There is no science that suggests that require admitting privileges makes abortion safer," she said.

In the U.S., three states -- Missouri, North Dakota and Utah -- currently require admitting privileges for abortion providers, while efforts to enforce similar requirements have been blocked in eight states, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Advocates for admitting privileges argue the law is simply meant to keep women safe.

According to the office of Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, Hope and other abortion providers in the state have "admitted on the record that they don’t have accurate data on complications."

"Louisiana abortion providers have a record of non-compliance with basic safety regulations, and now they want a special exemption from generally accepted medical standards that apply to similar surgical procedures in our state," Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry said in a statement in March, when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case. "Women seeking abortions deserve better than that; they should have the same assurance of prompt and proper care in the event of complications."

A 2014 study by UC San Francisco researchers of over 50,000 abortion patients in California found major complications occurred less than a quarter of a percent of the time.

What happens when patients don't have access to abortion care

In 2017, 9,920 abortions were provided in Louisiana, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Pittman described a "dark cloud" constantly over her head as she worries where those people -- who also travel from states including Texas, Arkansas and Mississippi -- will get help if the admitting privileges requirement is upheld and abortion providers in Louisiana are forced to close their doors.

"For a lot of women, this unplanned pregnancy is a crisis for them," she said. "And a woman who comes to us, more often than not, has decided this is what she wants to do."

The majority of patients who seek care at Hope Medical Group live at or below the federal poverty level, according to Pittman. She said the most common reason given for pregnancy termination by patients at Hope is "lack of financial stability."

"Often times, we hear from women that they need to make the best decision for the family they already have," she said. "They need to protect their family and make sure their family is OK."

Across the country, patients who are denied abortions face a "large and persistent increase" in financial distress in the years after, according to a working paper published earlier this year by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Looking at credit report data, researchers found that being denied an abortion increases the amount of debt 30 days or more past due by 78% and increases negative public records, such as bankruptcies and evictions, by 81%. The economic fallout appeared to be the worst for woman who were forced to have a child when they were not prepared to, the data shows.

In Louisiana, nearly 19% of the population lives in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Women who carry their pregnancies to full term also face health complications, data shows. While a small number of abortions require hospital care, the state of Louisiana has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the country.

Louisiana ranks second in the country in maternal deaths, behind only Georgia, with 44.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 lives birth, according to an analysis last year by U.S. News & World Report.

'It's shocking to me that nine years later the situation is worse'

The lack of access to abortion care that Pittman predicts would be made worse with an unfavorable Supreme Court ruling is what O'Brien experienced in 2011 when she learned at her 20-week ultrasound that the fetus she was carrying had "severe brain abnormalities."

After seeking second, third and fourth medical opinions and talking to trusted family and friends, O'Brien, an attorney, and her husband, a medical doctor, decided to terminate the pregnancy.

"It was all bad news and would not have resulted in a healthy baby if it was to survive to the end of the pregnancy," said O'Brien. "At that [ultrasound] appointment, our doctor told us, 'You know, you have a lot to think about. If you decide that you want to terminate the pregnancy, the clock is ticking. There are restrictions in Louisiana.'"

"I knew that I had a legal right to an abortion, but I just didn't know much about the practicalities," she said. "I assumed that I would just go back to my doctor and say, 'OK, we're ready.' I was wrong."

O'Brien said her provider told her he could not perform the procedure and she was advised by other doctors that her "best bet" was to travel out of state. She had to do research on her own to see if laws in nearby states would allow her to have an abortion there. By the next year, 2012, the state enacted a ban on abortions after 20 weeks of a pregnancy, with limited exceptions.

She also had to find a doctor on her own and says it was only thanks to her husband's medical network that she found a doctor in Texas who would perform an abortion at her stage in pregnancy.

O'Brien and her husband drove six hours from their home in New Orleans to Houston for the procedure. They had to take time off work, arrange childcare for their daughter, who was 1 at the time, and pay for a three-night stay at a hotel.

"I was given no guidance and I know that I have privileges that the vast majority of women don't have," she said. "I have a legal education. My husband has a medical education and training. We have this vast social and professional network of other healthcare providers. We have financial resources ... we had my parents' support and availability to keep our child for three nights. My husband was able to take off work, which so many people don't have the ability to do."

"All of those things I know that the average person does not have, and still it was near impossible for me to get the abortion," said O'Brien, who experienced an additional logistical complication once she was admitted at a Houston hospital for the procedure.

O'Brien said that after waiting for hours in her hospital room, her doctor told her the hospital's board had changed their policy a week prior to say they would no longer allow abortions beyond 20 weeks. The hospital had not yet informed the OBGYN department about the new rule but hospital officials said her procedure could not move forward, according to O'Brien.

"Ultimately they connected with another abortion provider who had a clinic in the area, and I had to be taken by wheelchair across the street to a medical office building where they started the procedure, and then I had to be wheeled back to the hospital so that they could complete the abortion," she said. "It was absolutely insane and had nothing to do with my health or anyone's health."

In the 2016 case, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in a concurring opinion that "Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers laws that 'do little or nothing for health, but rather strew impediments to abortion' cannot survive judicial inspection." Even so, lawmakers and judges have moved forward with similar laws in many states, as the Louisiana case shows. O'Brien says that if her circumstance had occurred today, she would not be able to get an abortion in either state due to additional laws enacted in each state.

"It's shocking to me that nine years later, the situation is worse," she said.

ABC News' Alexandra Svokos and Devin Dwyer contributed to this report.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify restrictions O'Brien faced and add detail on complications.