Breaking down the Supreme Court nomination, confirmation process

The death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg -- 46 days ahead of the presidential election -- has prompted new scrutiny of the process of approving nominees to sit on the nation’s highest court.

President Trump is expected to put forth a nominee to fill her seat today, multiple sources close to the president and with direct knowledge of the situation told ABC News.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said last week that Trump’s nominee will receive a vote on the floor of the Senate.

How a position opens up

The ever-evolving makeup of the country's highest court stems from the lifetime nature of the position.

Once a justice dies, retires, or resigns, the sitting president has the constitutional power to nominate a replacement.

Voluntary retirement has been the most common way justices leave the Supreme Court, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service (CRS). That’s been the case for the vast majority of departures since 1954.

Until now, only two of the remaining vacancies during that same time period, since 1954, were a result of a justice dying while in office, the Congressional Research Service reports.

It was more common for justices to die while in office in the half century before, however, as 14 of the 34 vacancies that came between 1900 and 1950 fell in that category. And there was a stretch from 1946 to 1954 where the five justices who left the bench all died while in office, the CRS reports.

One other, very rare departure method, is impeachment. Congress can remove a Supreme Court justice through impeachment, and much like a presidential impeachment, a justice would both have to be impeached and then be convicted in a Senate trial before being removed. In the history of the court, there has only been one justice, Samuel Chase, who was impeached, back in 1804, but the Senate acquitted him so he didn't leave the court, according to the CRS.

The first steps

When Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement from the court in June 2018, Trump was able to make his second Supreme Court nomination, nominating Brett Kavanaugh in July 2018.

(Trump first picked Neil Gorsuch, who was approved in 2017, to fill the seat of Justice Antonin Scalia after his unexpected death in 2016.)

When Kavanaugh, the most recent pick, was nominated, he spent much of the next nearly two months meeting with senators and collecting documents and records in preparation for the upcoming hearings.

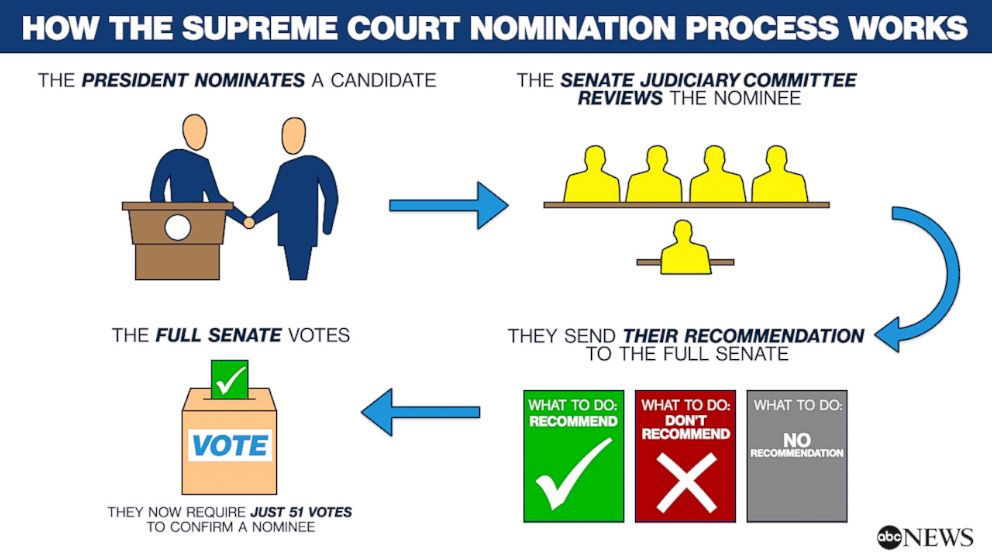

The Senate is constitutionally empowered to "advise and consent" on Supreme Court picks. That starts with the Senate Judiciary Committee holding hearings on the nominees.

When the hearings are done, the committee holds a vote to recommend to the full Senate whether the nominee should be confirmed, rejected, or, in some cases, to make no recommendation.

In the case of Kavanaugh, the committee vote was in Kavanaugh’s favor but with the caveat that additional FBI investigation be done over one week into an allegation he committed sexual assault in high school, which he denied.

The full Senate debate, cloture and the final vote

In normal scenarios after the committee vote, the full Senate holds its own debate on the nominee before voting.

Senate debate is unlimited unless ended by cloture, which calls for the end of discussion on a certain topic. The motion has to be put forward by a group of 16 senators and then must be passed by the full Senate before going into effect.

The vote on a cloture motion doesn't happen immediately. The operating rules dictate the vote on the cloture motion happens "on the following calendar day but one," which means not the day after the cloture motion is proposed but the second day after.

Going 'nuclear'

Traditionally, three-fifths of the Senate -- or 60 senators -- had to vote for a cloture motion in order to move to a final vote on a Supreme Court nominee.

That said, the Senate changed the rule in April 2017 by lowering the threshold to 51 votes to move forward and for final approval. Republicans triggered the new lower threshold, known as the "nuclear option," to eventually get Gorsuch confirmed.

The reason why McConnell did so then was that Republicans would not have had enough votes to secure his nomination if the 60-vote requirement were in place. So, instead, he got Gorsuch confirmed 54 - 45 on April 7, 2017.

Because of the 2017 rule change, the minority has little power in the Senate unless members of the majority power join them -- which could be the case with Trump's pick to replace Ginsburg.

The vice president can break any tie vote given his role as the president of the Senate.