Summer's ending. How are US schools' reopening plans still in crisis?

In mid-July, seven weeks before the start of its school year, the Philadelphia school district announced it planned to reopen in a hybrid model, with both in-person and online learning. The decision came, the school board said, after months of collaboration between city leaders and public health experts, as well as feedback from more than 35,000 survey respondents.

Then, nearly two weeks later, it scrapped its hybrid proposal and planned to reopen fully remotely to start, following pushback from parents and faculty at an 8-hour school board meeting that ended after midnight.

Though just one of more than 13,000 school districts across the country, Philadelphia demonstrates the challenges and questions remaining in reopening schools as fall approaches. A nearly identical scenario played out in Chicago last week, where the school district reversed course on its plan for in-person learning a month before the start of the school year. New York City, the largest school district in the country, is facing pushback from teachers and union heads over its plan to reopen partially in person next month.

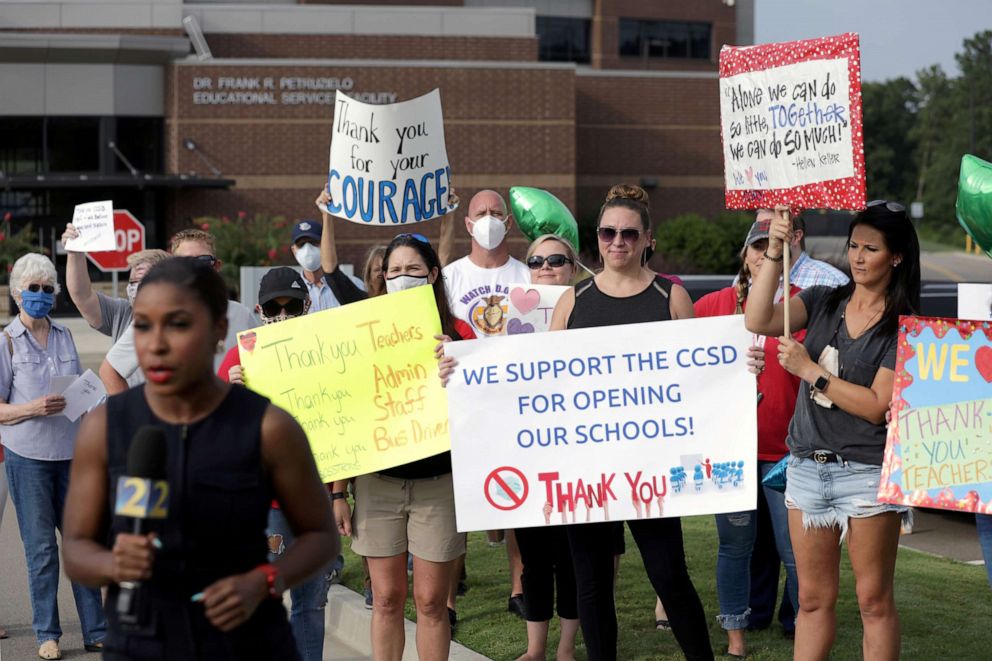

Some parts of the country, particularly in the South, have already opened their doors to a new school year. But days in, their openings have been marred by reports of outbreaks and quarantining over positive cases of COVID-19 among students and staff.

It's been six months since the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic and schools abruptly closed, and as a new school year approaches, little has been clarified about how it will look. Rather than work out set, manageable plans guided by science, schools have spent the past half year caught between a lack of guidance, the politicization of reopenings and what seems to be a growing national complacency.

'Extremely high stakes'

As schools and families consider sending students back in-person, the virus is raging in hot spots across the country, vaccines are likely months away and there's still much to learn about transmission, especially in children.

By a slight majority (55%), most Americans are against public schools in their community reopening with in-school instruction in the fall, a recent ABC News/Ipsos poll found. Parents willing to send their kids to school have waned since June, from 54% in early June to 44% in late July.

School leaders are weighing the risks of keeping children in or out of the classroom, from the safety of its community to lost learning time and widening opportunity gaps.

"There's both a lot of uncertainty about what to do and there are extremely high stakes to the decision," Jon Valant, a senior fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution, told ABC News.

And logistically, schools need to train teachers for virtual instruction and/or obtain masks and hand sanitizer, create lunch and bathroom protocols, rearrange seating, plan for potential teacher shortages and more.

"There's a lot of planning that has to happen for in-person, there's a lot of planning that has to happen for virtual," Valant said. "And then there are a million different contingencies that everyone has to think through."

Reopenings politicized

What school leaders need to help navigate these circumstances, Valant said, are "generous resources" to support reopening online learning as well as good research, but also "deference" from state and federal leaders.

"They would understand that what is the right decision in one place might not be the right decision in another place," he said.

Instead, President Donald Trump and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos are "taking a really hard line that schools should reopen," he said.

For months, Trump has voiced on social media, in interviews and at press briefings that schools should open in-person. That message may be influencing local school decision-making, according to a recent Brookings Institution study Valant conducted.

In it, he analyzed school district reopening plans, representing some 13 million students in 256 districts, as of July 27 using an Education Week database. He found no relationship between local rates of new COVID-19 cases and school reopening plans. The main difference in school plans, the study found, came down to support for Trump. Districts in counties that supported Trump in the 2016 election were more likely to have announced plans to open in person, the survey found.

Amy Westmoreland, a school nurse in Georgia's Paulding County, resigned in mid-July when she learned her elementary school would be reopening in-person. She said she was not included in the reopening discussions.

"It's just very, very politically motivated there," Westmoreland told ABC News. "It's very unfortunate because I don't believe that the children, the teachers, anybody was really given the opportunity to voice their concerns."

Lack of clarity

As president of AASA, the School Superintendents Association, Kristi Wilson has been hearing from superintendents across the country -- and what she's hearing is a lot of anxiety.

"I don't think there's any question that superintendents across the United States want students back, want our teachers back, but we've got to do that safely," Wilson told ABC News. But, she said, "there's been a lot of missing guidance" from state and local leaders.

School leaders, she said, can prepare for new protocols like cleaning and sanitizing, but many still have questions about how long testing would take, how to perform contact tracing and how and when to close down parts of their facilities.

"The teachers and the educators are really good at teaching and building relationships. What we're not very good at, and shouldn't be good at -- it's not our lane -- is what happens when you have an outbreak," she said. "We want the county health departments and the medical field to tell us, 'This is when it's safe to open and this is when it's not safe to open.'"

Otherwise, she said, school leaders may be left on their own to interpret metrics.

Complacency and denial

Testifying before Congress in May, as many states were considering reopening their economies, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security's Caitlin Rivers, PhD, said "we risk complacency" in the fight against COVID-19.

"We risk complacency in accepting the preventable deaths of 2,000 Americans each day. We risk complacency in accepting that our healthcare workers do not have what they need to do their jobs safely. And we risk complacency in recognizing that without continued vigilance in slowing transmission, we will again create the conditions that led to us being the worst-affected country in the world," she said.

Testifying again last week at a congressional hearing on the challenges in safely reopening K-12 schools, Rivers said the "complacency I warned of has come to pass."

"Our case counts are worse now than they were in early May," she said, noting that the U.S. registered almost 2 million new cases in July and hospitalizations and deaths are on the rise in many states.

Meanwhile, "we still don't have sufficient testing capacity right now to enable the isolation, contact tracing and quarantine that will help us to get ahead of our outbreak," she said.

According to one former high school teacher in Georgia, the state has been in "great denial" about the risks of COVID-19, as attention in the beginning of the pandemic was focused on areas like New York City, which was hit hardest first.

"I think it's overconfidence mixed with denial," the teacher, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because she was concerned about future job prospects, told ABC News. "They didn't plan for the worst-case scenario."

Georgia was one of the first states to reopen its economy. Gov. Brian Kemp, who is Republican, has called for students to be in school in person. Last week, Georgia, which doesn't have a statewide mask mandate, became the fifth state to record 200,000 confirmed coronavirus cases.

The teacher recently quit ahead of her second year in the classroom because she didn't feel enough measures were being taken to limit class sizes. She was also concerned that masks were not required.

She said teachers were given a voluntary survey about a month ago asking if they'd be willing to come back or if they had an underlying medical condition and could not. "People definitely made a stink about that. There are a lot of different options in between that."

Teachers were not given an option to teach virtually, she said.

Westmoreland, the former school nurse, was also concerned that her school was not requiring masks and didn't feel that social distancing was being prioritized. She quit, she said, because she didn't want to be "complicit with their reopening plans," based on what she knows as a nurse.

Going remote first

Like Philadelphia and Chicago, an increasing number of school districts are starting the school year off remote to buy themselves more time to prepare for an in-person return. In some cases, that gives them time for preparations they could do themselves, like facilities upgrades, and in others, it's time to see if their region can bring testing positivity rates down, like in Los Angeles.

Virtual learning should be better organized than it was in the spring, when schools were "caught flat-footed" by the virus, Valant said. But there are still concerns about opportunity gaps expanding even further.

"When you start adding in issues related to things like home laptop and WiFi access, and whether students have a quiet dedicated workspace at home, and the differences in community vulnerability to COVID, I think there's a lot of reason to worry that some of the inequities that we've seen are getting a lot worse right now," he said.

According to a June AASA survey of superintendents, 60% of respondents said they "lack adequate internet access at home" when asked to identify barriers that would prohibit their districts from transitioning to fully virtual learning.

Jeff Gregorich, a superintendent in Winkelman, Arizona, told ABC News one of the biggest challenges in starting the school year has been providing students with iPads and WiFi hotspots to support virtual learning. Ahead of the school start next month, he has been working on deals with internet providers.

"It is costly. You need to sign a year contract with them," he said. "But we know that we need to provide that for our students."

Whether starting in-person now or planning to later, schools have another challenge on the horizon. Fall marks the start of flu season, and public health experts are worried about having both viruses at the same time -- further demonstrating the need for strong guidance and measured reopenings in the coming weeks and months.

ABC News' Esther Castillejo, Alex Colletta and Henderson Hewes contributed to this story.