What to know about 'Striketober': Workers seize new power as pandemic wanes

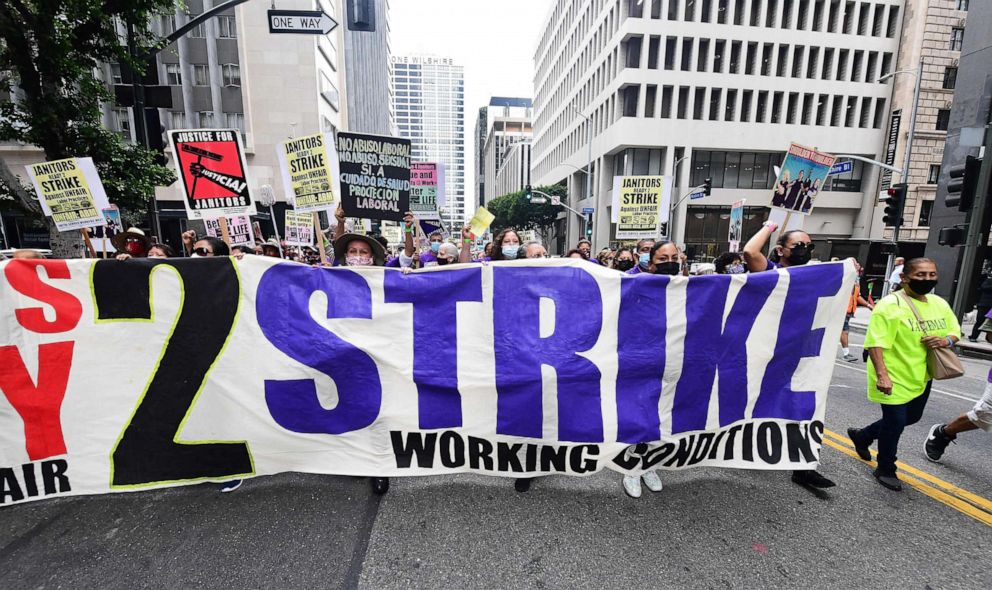

A spate of strikes has rocked the private sector, revealing the new power workers wield as the pandemic wanes in the U.S. and sending a message to employers who may have been working from home for the past year that a return to the status quo isn't going to cut it.

A confluence of unique labor market conditions -- including record-high levels of people quitting their jobs and an apparent shortage of workers accepting low-wage jobs -- has contributed to the recent rash of work stoppages, experts say, but they also come after decades of stagnating wages and soaring income inequality in the U.S.

The post-traumatic shock of a deadly pandemic that took an inordinate toll on workers who didn't have the privilege of earning a living remotely, and their families, has also been linked to the recent employee activism.

"I think workers have reached a tipping point," Tim Schlittner, the communications director of the AFL-CIO, told ABC News. "For too long they've been called essential, but treated as expendable, and workers have decided that enough is enough."

"They want a fair return on their work and they're willing to take the courageous act of a strike to win a better deal and a better life," he added. The AFL-CIO is a coalition of labor unions that collectively represents some 12.5 million workers.

Here is what to know about what some lawmakers are dubbing "Striketober," the recent labor movement uprising that has spanned across industries and states.

Who is striking?

There have been some 185 strikes at 255 locations this year, with at least 40 occurring in October, according to the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations' tracker. The researchers behind the tracker define a strike as a "temporary stoppage of work by a group of workers in order to express a grievance or to enforce a demand," that "may or may not be workplace-related."

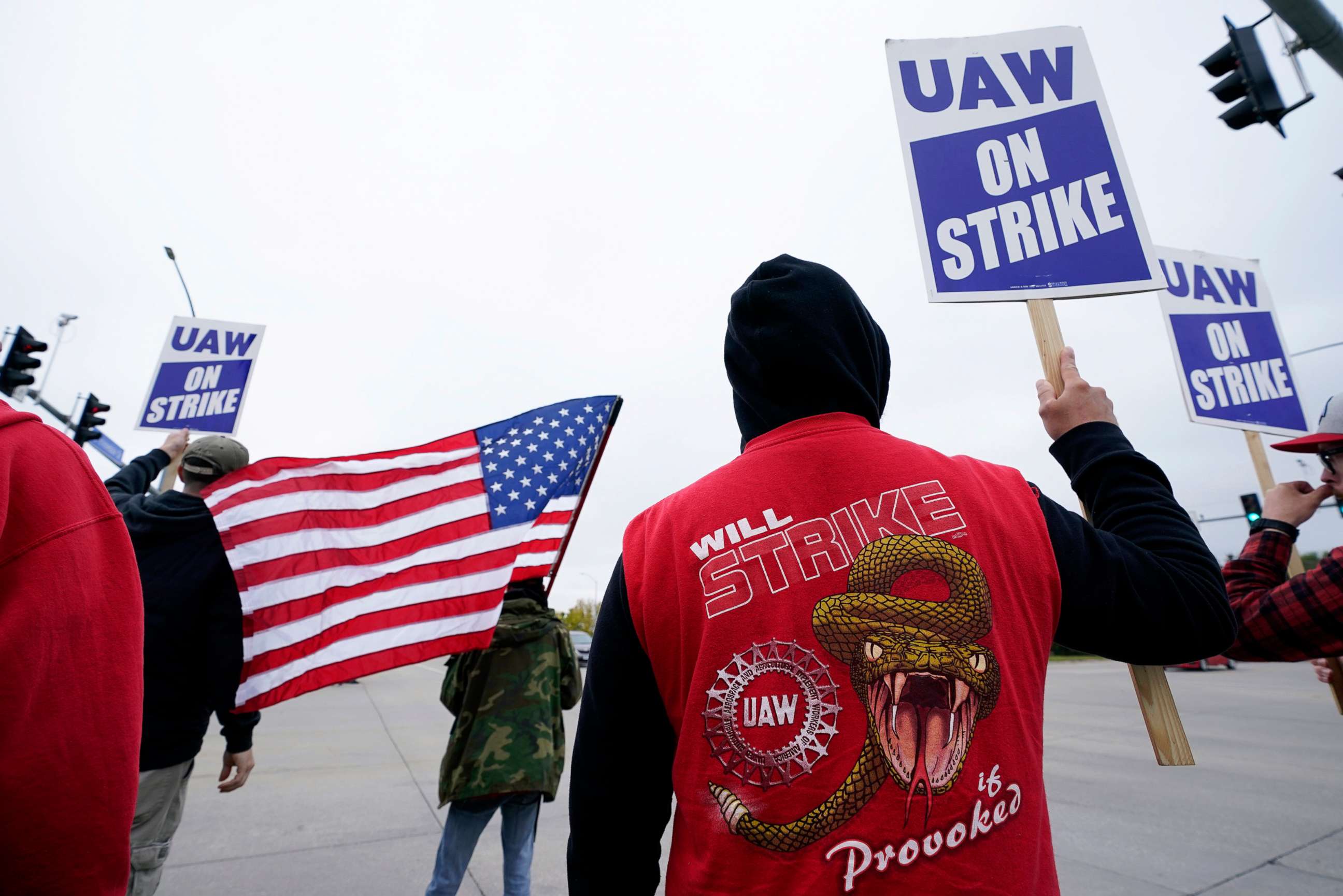

Among the most prominent is the ongoing strike of 10,000 John Deere workers across more than a dozen plants who are represented by the United Auto Workers. Some 1,400 workers represented by the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union are also on strike at Kellogg's plants across four states.

The Cornell researchers also collect data on "Labor Protests," defined as a collective action by a group of people as workers but without withdrawing their labor in order to express a grievance or enforce a demand. The group has tracked an additional 19 labor protests this month, and a whopping 554 in 2021.

The group collects information on strikes from Bureau of Labor Statistics data, Federal Mediation and Conciliation Services data, Bloomberg Law's work stoppage database, major media outlets, organizational press releases and social media. The researchers then follow a set of verification protocols to determine which instances constitute a strike or labor protest.

In 2020, as the pandemic raged, the Cornell ILR School recorded at least 54 strikes and eight labor protests.

Why now?

"I think it's a combination of things, but certainly influenced by the pandemic and the kind of economic situation coming out of that," Alex Colvin, the dean of the Cornell ILR School and a professor of conflict resolution, labor relations and law, told ABC News.

"People feel like they contributed a lot during the depths of the pandemic and now they're looking for some of the returns when the economy's doing better and companies are doing better -- profits are up, stock prices are up," he added. "We're seeing similar effects going on with quit rates going up, people more willing to leave their jobs now and look for something better."

The Bureau of Labor Statistics said in a release earlier this month that the number of people who quit their jobs in August jumped to the highest since its record-keeping began, representing nearly 3% of the entire workforce. The record-high quit rate bested the previous high of 2.7% that was set in April of this year, and then repeated in June and July.

As the number of people quitting their jobs has reached record highs in recent months, so have the number of job openings, the BLS data indicates.

Meanwhile, a dismal 194,000 jobs were added to the economy last month, according to BLS data, as employers struggled to fill positions. This was lower than the already-disappointing figure of 366,000 in August, and the million-plus jobs added in July.

Due to working through a COVID-19 pandemic that has left more than 730,000 Americans dead, and because of the recent labor market trends, workers may be "less willing to take what they've been willing to take in the past," Colvin said, but added that these factors also increase the leverage unions have when executing a strike.

"It makes sense for workers to push to kind of share in the gains of the improving economy," he said. "But also, they have more leverage because it's harder to replace them in a tighter labor market."

The AFL-CIO's Schlittner said the pandemic also exposed some deep "imbalances of power in the economy."

"The pandemic has made clear what's important and what's not, and workers are looking at work in a new way, and demanding more of a return on their labor, and demanding things like basic respect, dignity and safety on the job," Schlittner told ABC News. "The pandemic has put on display for everyone to see how important workers are to this country, and you can't call workers essential for 18 months and then treat them like crap when they all come back on the job."

What's causing the so-called 'labor shortage'?

Recent labor market data has sowed confusion for some over where workers have gone. The unemployment rate as of last month remains at an elevated 4.8%, still above the pre-pandemic 3.5% seen in February 2020. The number of job openings, however, has hit record high after record high in recent months -- with the most recent BLS data indicating that there were some 10.4 million job openings in August after a record-high 10.9 million in July.

A report from Moody's Analytics released earlier this week attributed the workforce reduction in large part to child care issues, which have plagued working parents and taken a disproportionate toll on mothers during the pandemic, and was the most-cited reason for why people aren't returning to work. The Wall Street analytics firm also found that millions not working said they were out of work because they were laid off or their employer had gone out of business during the pandemic, and some economists have attributed pandemic-era protections and government support to their slower return to the workforce. Finally, their data indicates fear of getting or spreading the virus was heavily cited among those not working.

Schlittner said he doesn't see it as a labor shortage, but rather "a shortage of good-paying jobs."

"There's a shortage of good-paying, quality jobs; that's the scarcity story in America today," he said. "If employers raise pay, improve working conditions and give every worker the right to form a union, the workers will be there, ready to report to the job."

Some data indicates the power that lack of laborers willing to accept low pay can have on pushing up wages, and the power of collective activism.

The federal minimum wage has remained unchanged for over a decade at $7.25 an hour, despite widespread activism -- especially in the hospitality industry -- to raise that to $15 an hour through organizations such as the Fight for 15. Post-pandemic demand for staffers as restaurants reopen has pushed the average hourly wages of workers at food and drinking establishment to a record-high $17.40 an hour in August, according to preliminary data from the labor department.

Meanwhile, a GoFundMe started in support of the John Deere workers on strike has garnered over $80,000 in just four days from more than 2,000 donors.

"More workers are recognizing the power in each other, that standing together with their co-workers is a powerful act, and can bring about great change," Schlittner said. "And that's what 'Striketober' is all about. It's about changing an economy and a system that isn't working for regular working people. One picket line at a time, we can start to do that."