As stocks soar to historical highs, some experts say conditions ripe for correction

The stock market has been a roller coaster ride in recent weeks, with wild swings from day to day at times.

The major indices have also hit record after record this year as the as the economy roared back from pandemic lows and the government flooded the economy with stimulus cash.

The S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite indices, for instance, closed at record-highs last month, besting highs that were only just set earlier in the year, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average of 30 large company stocks closed at a record-high a month prior. Despite a pandemic-battered economy, the S&P 500 and tech-heavy Nasdaq are both up approximately 30% compared to the same period a year ago, and the Dow is up more than 20%.

The trends have left some experts wondering whether the ground underlying the rapid growth of the market, fueled in part by a new crop of retail investors, is solid, or if there is a bubble building.

Risks abound, from the debt ceiling crisis to inflation fears and even China's Evergrande saga, which have led to daily swings.

But even as markets have fallen on news, the newfangled hashtags like #BuyTheDip (which encourages market participants to buy rather than sell during these down periods) and #DiamondHands (encouraging investors to hold onto assets rather than sell) often trend on Twitter in tandem with the fear-ridden headlines. Even the Fed has warned of vulnerabilities associated with the "increased risk appetite" demonstrated by retail investor exuberance seen in the "'meme stock' episode."

While the pandemic's abrupt disruption to American life is another reminder that it's impossible to predict the future, historical patterns and the precariousness of present market conditions have some economists warning that current growth rates may be unsustainable, especially amid inflation worries and potential tightening by the Fed of monetary policy.

Here's what we know and don't about the market landscape:

Key overvaluation indicator at highest level since the Dotcom bubble

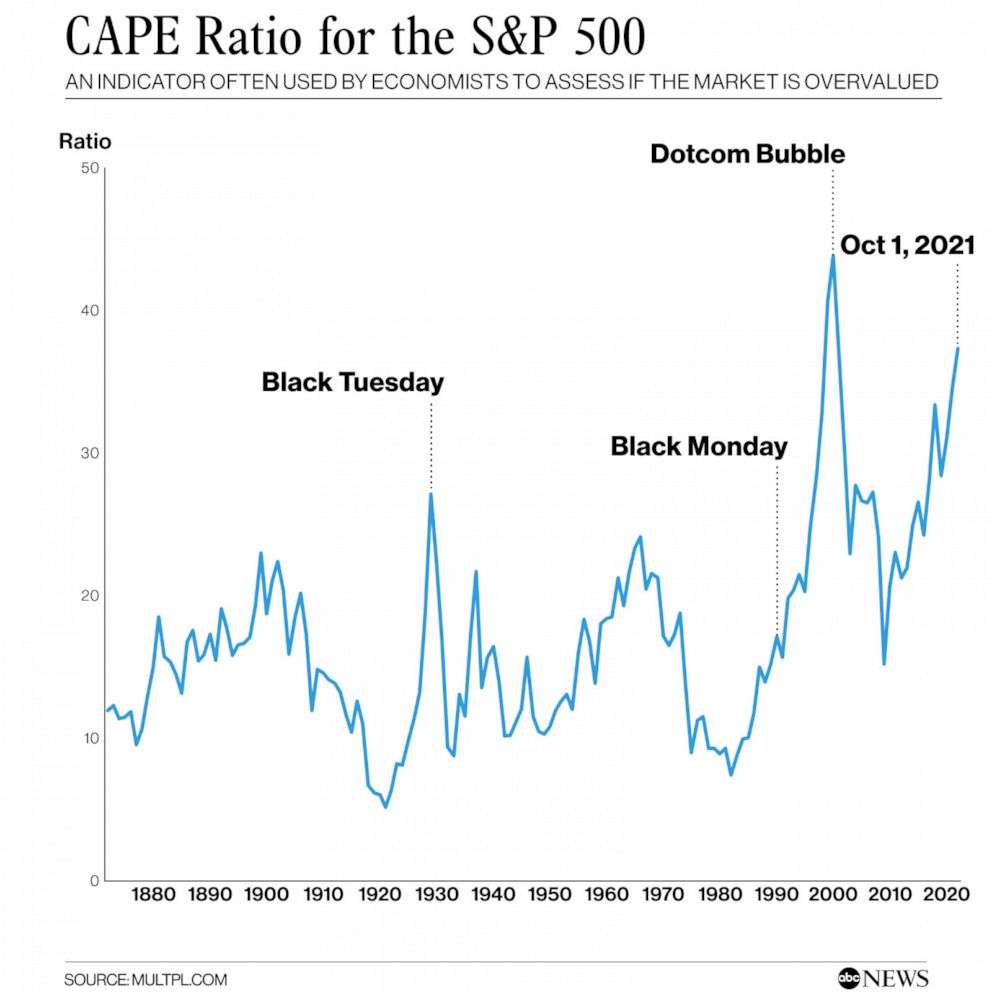

One measure often used by economists to predict a potential asset price bubble is the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio, developed by economist and Yale University professor Robert Shiller. The measure looks at firms' inflation-adjusted real earnings per share over a 10-year period to indicate possible over- or under-valuations.

Itay Goldstein, a professor of finance and economics at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business, told ABC News that the measure is essentially used as "an indication for whether the stock price is too high or not."

When Shiller first published his research in 2000, he pointed to how high stock prices were at that point relative to the fundamentals that should underly their prices. His book, "Irrational Exuberance" appeared in March 2000, highlighting how psychological factors can produce speculative bubbles and as it appeared, the tech-heavy NASDAQ Composite index began a 78% drop and the broader U.S. stock market took a 64% fall.

Presently, the CAPE Ratio hovers at around 37, its highest level since the 2000-2002 Dotcom crash -- higher now than the 30 it reached before the Black Tuesday crash in October 1929 that triggered the Great Depression. The historical mean is 16.8.

There have been criticisms of CAPE. Jeremy Siegel, a professor of finance at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business, has argued in research that changes in accounting standards cause the earnings data to be biased downwards and thus the CAPE to be biased upwards. Others noted that the CAPE uses past earnings, but what investors are interested in is future earnings.

"You basically see that it's now still in historically high levels," Goldstein said of the CAPE Ratio. "If you go back in history, it was higher than that only around 2000 before the big crash of the Dotcom bubble, it wasn't even at that high a level in 2008 before the big financial crisis." In May 2008, before stocks started falling, the CAPE was 23.70.

"It's been high for a long time, and there was this crash last year when COVID started and then it climbed back up very quickly and continued to climb since then," he added. "It's hard to predict what will happen, but certainly it could be that the level is too high and there could be some correction."

Fears of overvaluation are not new, especially in the tech sector where the value of certain traditional fundamentals or research and development may be harder to quantify. Many tech companies are not earning profits now, but people are investing based on the hope that they will earn in the future. A measure such as CAPE that uses past earnings will not be useful for evaluating these companies.

Tech sector and risk appetite

Many market watchers, for example, have been ringing alarm bells surrounding the sky-high growth of Tesla stock in recent years -- arguing that its value does not align with its production output and fundamentals. On paper, the argument seems valid: Tesla's market cap, some $775 billion, is larger than the next five largest automakers combined.

Yet some with so-called #DiamondHands who have been able to ignore this have seen themselves become "Teslanairres" in recent years as the electric vehicle maker's stock value continues to climb.

Tesla aside, overvaluation estimates for the stock market as a whole is "speculative," Goldstein said.

"People can tell sort of an economic story that will justify -- my overall feeling is that it's too high and it's hard to justify that based on fundamentals," Goldstein said, referring to the market as a whole.

While he stresses it is ultimately difficult to know for sure whether stock prices are creeping towards a bubble, Goldstein said that, "The indicators that we see, I think give us some reason to be worried that stock prices might be too high."

The Federal Reserve also warned off rising asset prices being vulnerable to "significant declines should risk appetite fall," in its semi-annual Financial Stability Report released in May, noting that "prices are high compared with expected cash flows."

Fed Governor Lael Brainard pinned increased appetite for risk and rising valuations in part on retail investors, referencing "the 'meme stock' episode" in a statement accompanying the report.

"Valuations across a range of asset classes have continued to rise from levels that were already elevated late last year. Equity indices are setting new highs, equity prices relative to forecasts of earnings are near the top of their historical distribution, and the appetite for risk has increased broadly, as the ‘meme stock’ episode demonstrated," Brainard said.

The increased appetite for risk has also been seen in the bond market, Brainard added. "The combination of stretched valuations with very high levels of corporate indebtedness bear watching because of the potential to amplify the effects of a re-pricing event," he said.

Unique market conditions and inflation woes

When COVID-19 upended the economy in the spring of 2020, unemployment levels in the U.S. reached highs not seen since the Great Depression as lockdown orders forced businesses to shutter. In the midst of the crisis, the stock market fell sharply in March (when it had been at record highs) -- but then rallied back to reach new highs within months.

Much of the pandemic stock markets gains can be pinned in part to aggressive monetary policy by the Federal Reserve in response to the pandemic, some economists say. The Fed pulled out all of the stops, slashing the target for overnight interest rates to almost zero, buying massive amounts of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, encouraging bank lending and taking other steps to sustain the flow of credit.

"What the Fed has done is it reacted to a public health crisis," Philip Schnaebl, a professor in finance and asset management at New York University’s Stern School of Business told ABC News.

"Now, the economy looks much stronger, obviously there's still risks with [the] delta [variant] and what's happening in emerging markets and so on," Schnaebl, who is also a research associate in corporate finance at the National Bureau of Economic Research, added, "But employment growth has been pretty strong, it looks like the public health crisis is not as severe as it used to be."

If the Fed starts tapering its purchases of securities -- which it signaled after its Sept. 22 meeting that it would likely start doing soon -- and when it looks to start raising interest rates, many economists are bracing for what this could mean for the stock market. The Fed has been buying Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities each month starting in March 2020. Tapering means the Fed would slow its purchase of these assets.

Ending these pandemic-era policies would "lead to slow deflation of stock prices," Schnaebl said.

The Fed said it found concerns that a change in monetary policy, especially if the economic outlook hasn't improved, could lead to a "correction for risky assets," according to the investors , academics and more it surveyed as part of its market intelligence gathering for its Financial Stability report.

"Contacts observed that valuations of many assets have derived significant support from low discount rates and therefore may be susceptible to a spike in yields, especially if unaccompanied by an improvement in the economic outlook," the report said.

Overall, Schnaebl said he thinks the Fed has its "eye on the ball" and will be able to respond to stock market dangers that could spill over into the economy as a whole.

One possible wrench in the Fed's machine, however, would be if inflation takes hold and the central bank could no longer implement expansionary policy. Data from the consumer price index has stoked inflation fears, though the Fed has largely said that it should be temporary due to labor and supply chains issues as the economy emerges from the COVID-19 shock.

Historically, the stock market has served Main Street in the long run

Retail investors have pumped billions into the stock market in 2021, with some economists linking this to the rise of investing apps and pandemic stimulus funds that were distributed at the height of stay-at-home orders.

Ultimately, Stern's Schnaebl says it is hard to tell until after the fact if stocks are overvalued and a crash looms.

"There can be a lot of volatility in the short run, that's why the stock market is risky," he said.

"I'm less concerned about the stock market just on its own, sort of falling," he added. "I'm concerned about the health crisis and if that worsens, I think it would show up in the stock market."

A sudden drop in stock prices "would be bad, not necessarily because the stock market crashed, but probably because something else happened which made the stock market crash and that's not good news for the economy."

While price corrections can be scary for investors, they can also be viewed as a part of how equity markets work when prices adjust to reflect longer-term values.

Goldstein notes that asset "prices are just high, they are high across the board, across multiple assets." He sees a "significant likelihood" that stock prices will fall. The trigger for this could be monetary policy tightening, news coming out of China like Evergrande's threat to destabilize the international financial system, or some other factor.

"People are looking for where to put to put their money and make a decent return," Goldstein said of the new excitement in the stock market. "With all this in place, I think you have a combination of factors that contribute to high prices, and there could be a trigger that could come from different places that will eventually start the drop."

Even if economic outlooks in the labor market and beyond are positive outside of stock prices, Goldstein notes a sudden drop would impact the real economy as firms "become more cautious" by spending and investing less.

Many major Wall Street players are feeling the uncertainty. Over three-quarters of respondents to a CNBC Delivering Alpha investor survey say now is the time to be very conservative in the stock market when asked what kind of market risk they are willing to accept for themselves and their clients. Respondents include some 400 chief investment officers, equity strategists, portfolio managers and contributors to the financial news outlet.

Schnaebl noted that if a drop were to happen, "The question is why does it happen, and usually these things don't come out of the blue."

"I tend to think of the stock market in many ways is a reflection of what's going on in the economy rather than this is independent entity which is driving other things," he added, noting that if the a drop were sparked by the worsening of the virus it would be a blow to the economy as a whole that's reflected in the stock market versus not the other way around.

Still, the stock market has historically been a useful vehicle for those with #DiamondHands looking to save over the long term.

"For investors -- especially people saving for retirement and thinking about where to put their money so they can have a safer time in 10 to 30 years from now -- historically, the stock market has been a good place," Schnaebl said.

"My advice to everyday investors would be two things: first of all, diversify," Schnaebl said, "And second of all, invest for the long run."