As states cut vaccine exemptions, skeptical parents may switch tactics

When Vermont became the first state in the nation to eliminate personal belief exemptions for vaccines in 2016, some wondered if parents would claim religious exemptions instead, regardless of whether or not they were religious.

Three years later, there’s data to support that theory.

A new study, published in the journal Pediatrics on Monday, found that after lawmakers outlawed personal belief exemptions, there was a seven-fold increase in the percentage of Vermont kindergartners with religious exemptions, with exemptions growing from 0.5% percent during the 2011-2012 school year to 3.7% during the 2017-2018 school year.

Overall, non-medical exemptions fell 2% in Vermont, down from 5.7%.

“We interpret that as of evidence of a replacement effect,” said Dr. Joshua Williams, lead study author and pediatrician at Denver Health Medical Center.

While the study identified a correlation, not a cause-and-effect scenario, evidence from other states have followed similar trends. California, for example, saw medical exemptions rise when the state eliminated its personal vaccine exemptions shortly after Vermont did. (California’s personal exemption category includes religious reasons for not vaccinating.)

With the resurgence of measles in the United States, including outbreaks at Disneyland, in Minnesota and Brooklyn in recent years, the vaccine landscape has changed, as states tighten or eliminate exemptions in an effort to improve vaccination rates.

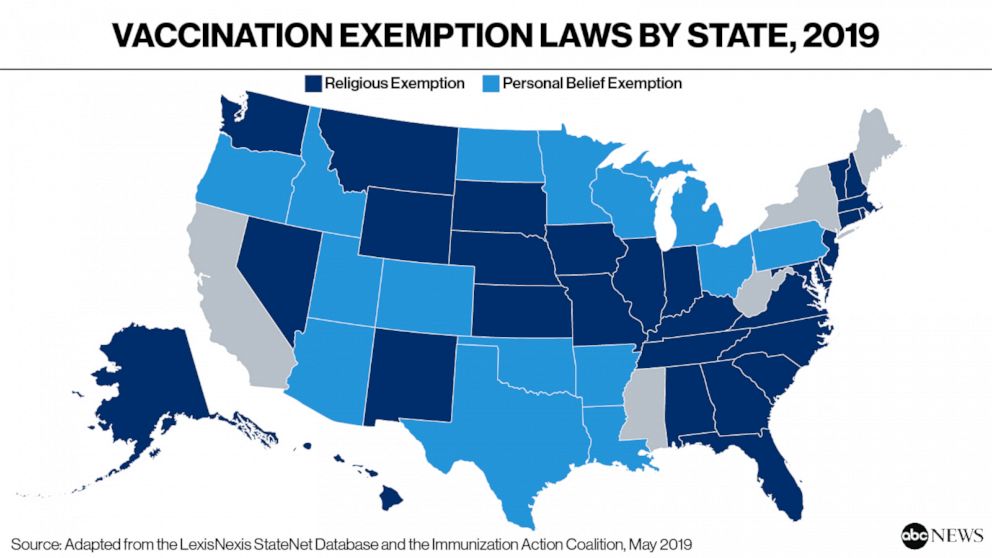

Five states now ban all non-medical exemptions, with two states, New York and Maine, implementing those rules this year. Forty-five states continue to permit exemptions for religious reasons and 15 still allow exemptions for personal reasons.

Importantly, it’s still a small percentage of kids who have vaccine exemptions.

“The vast majority of parents believe that vaccines are safe and effective,” Williams said.

Nationally, religious exemption rates have risen over time in states that allow religious exemptions only. Exemption rates among American kindergartners in those states tripled between 2005 and 2013, then plateaued for three years. Now, they’re starting to rise again.

At the same time, Americans are increasingly less religious.

In a 2014 survey, 22.8% of Americans reported having no religious affiliation, compared with 16.1% of Americans who said they weren’t religious in 2007, according to the Pew Research Center.

Vermont was not an outlier in that group. In 2014, Vermont was ranked among the least religious states in the country.

Williams worried about the unintended consequences of an uptick in religious exemptions as Americans simultaneously become less religious.

“If we if we obscure why parents are exempting, we are losing transparency,” he said.

There’s also the prospect that religious communities could be stigmatized for those exemptions, even if they’re not the ones claiming them.

“A sudden increase might alienate religious communities, and even alienate leaders in communities who are otherwise pro-vaccine,” Williams said.

Williams' fear isn't hypothetical. Earlier this year, as a measles outbreak erupted in an Orthodox Jewish community in New York State, there was a spike in harassment and antisemitism specifically related to measles. Residents said they crossed the street or wiped down bus seats when they saw an ultra-Orthodox Jew, the New York Times reported.

As it stands, all major religions support vaccination.

“An important question to ask is whether or not religious exemptions are still relevant in an increasingly secular and spiritual society,” Williams said. “That's the tough work that lawmakers have to do.”