How a star surgeon's personal and professional lives converged to expose his lies

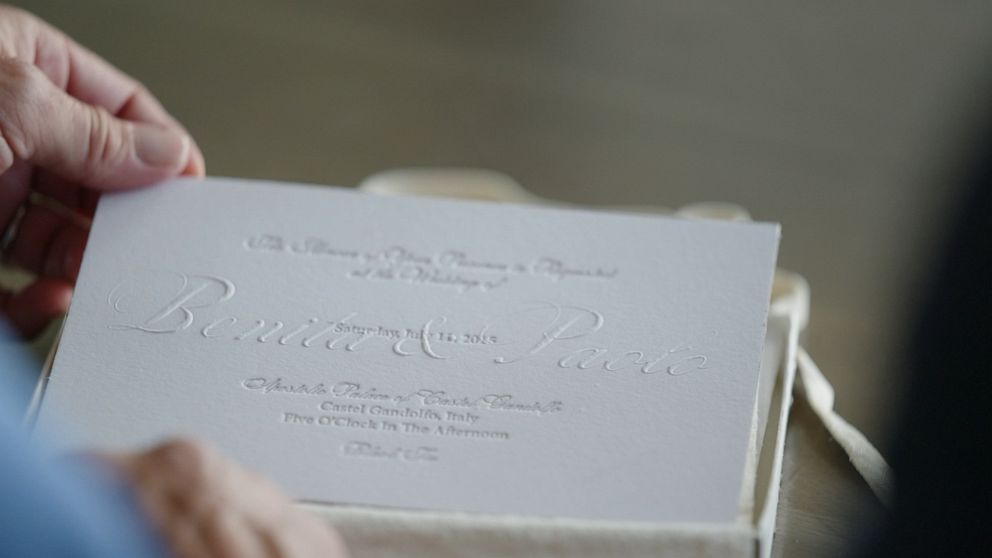

Hundreds of Benita Alexander's friends and family had already bought their plane tickets to Italy to attend her extravagant wedding that was supposed to be officiated by the pope when it all came crashing down in a flurry of her fiancé's deception.

None of the promises Alexander said her fiancé Paolo Macchiarini had made for their wedding day would come true. As Alexander began to unravel the web of lies Macchiarini had told her, she began to wonder if the world-renowned thoracic surgeon had also misled people in his professional life.

"As furious as it makes me what he did [to me and] my daughter, the thought that this is a man who has people's lives in his hands. This is a surgeon. … People could be dying because of this man, and therefore, I couldn't stay silent, I couldn't crawl under the covers. … I had to expose him."

See the shocking new details about Paolo Macchiarini's alleged medical crimes, new interviews and new revelations Friday on "20/20" at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

She soon discovered that as she lived an apparent fairy tale romance -- with someone who not only seemed to care for her and her daughter but also lavished her with expensive gifts and trips -- others were already searching for the truth about Macchiarini.

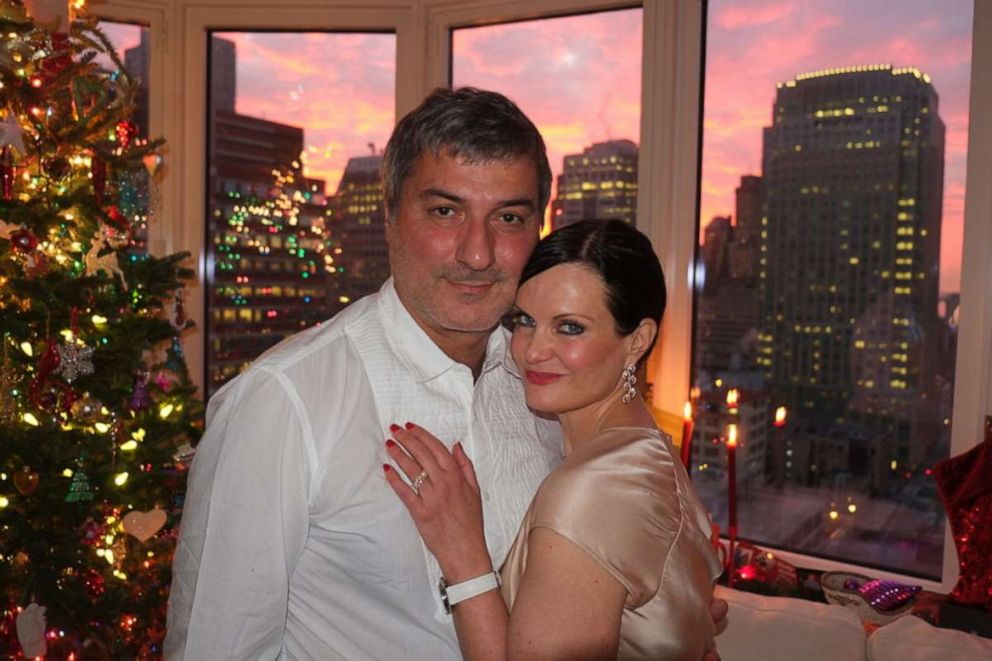

Benita Alexander and Paolo Macchiarini fall in love

Alexander, an award-winning documentary TV producer, met Macchiarini in 2013 while working on a story about the surgeon's pioneering work transplanting synthetic tracheas, or windpipes. The procedure uses the framework of a plastic tube lined with the patient's stem cells and is intended to help them replicate into a healthy version of the failing organ.

At the time, Macchiarini was employed by the prestigious Karolinska Institute in Sweden. He traveled to Illinois to operate on a Korean toddler who was born without a trachea and who was going to be the youngest person to ever receive an artificial one.

Sought after worldwide, people believed Macchiarini would one day revolutionize the field of organ transplantation, journalist Bo Lindquist said. Some even believed he'd win a Nobel Prize one day, according to author Stuart Ritchie. Both have covered Macchiarini in their work.

Alexander said she never thought she'd be part of Macchiarini's life, particularly because he was a subject in her work. But on the afternoon that she met him, a day before she was supposed to begin filming him, something happened that gave her pause.

"It was the weirdest thing," Alexander said. "He comes around the corner, he looks right at me and in that second something happened. I mean, I got this sort of chill through my body, like there was some sort of electric spark, and I remember, in my head, thinking, 'What the hell was that?'"

As a journalist, Alexander knew she couldn't get involved with the subject of her story.

However, while filming with Macchiarini, Alexander's ex-husband, the father of her young daughter, had been diagnosed with brain cancer. He was dying and Macchiarini became someone Alexander could lean on.

"Paolo was a really good listener," Alexander said. Macchiarini had told her that he and his wife were separated, but that the divorce hadn't yet been finalized legally. "He and I started going to dinners and I was kind of pouring my heart out to him about all this stuff. He gave me really sage, solid, kind advice."

When her ex-husband died, Macchiarini helped Alexander cope. On the back of his motorcycle, he drove her along the Illinois River until they found a place where she could memorialize her ex-husband.

Alexander said that day marked the beginning of their relationship. Soon afterward, he took her on an "over the top" romantic trip to Italy, where they ate extravagant meals, went shopping and island hopped on a private boat, she said.

She said she'd never fantasized about a "Prince Charming." But Macchiarini showered her in flowers and jewelry. He wrote love notes in lipstick on her mirror and left roses on the bed in the shape of hearts. Together, they'd spend long weekends traveling to different countries, like Mexico, Russia and Greece.

"Her life suddenly went from very down to earth to this kind of glamorous, almost celebrity lifestyle… I was like, 'What is happening to Benita,'" Alexander's friend, Marian Fontana, said.

He proposed to Alexander on Christmas in 2013 and she said yes. Then, just before New Year's Eve, he left the U.S., telling Alexander that he had a "really important surgery" to perform.

"I have some really high-powered clients," she said he told her. "That's when he told me that there was this kind of clandestine network [of doctors] who are on call, basically, for these people.'"

Among the high-powered clients who Macchiarini claimed were on this network were the Clintons, the Obamas and even Pope Francis.

But despite his seemingly busy schedule, Alexander said Macchiarini offered to plan their wedding. They had already decided to marry in Italy, where Macchiarini wanted a Catholic wedding despite rules against remarriages. Macchiarini told Alexander he was having difficulty finding a Catholic priest who would marry two divorcees, but he told her not to worry, he would talk to his contact in the Vatican.

Alexander said Macchiarini later called her, telling her he was at the Vatican and that he had some big news: Not only did he find someone willing to perform the ceremony but he said it was his own patient, the pope himself.

Alexander didn't initially believe him, but she said Macchiarini told her that the pope wanted to push forward his progressive agenda for the church. After doing her own research, Alexander found that Pope Francis had just married 20 couples and began to believe it was possible after all.

"From that moment on, it felt like my head was spinning," Alexander said, "and it didn't stop spinning."

She said Macchiarini had told her that for their wedding, the Vatican had offered them the pope's summer residence in the Italian town of Castel Gandolfo. He told her opera singer Andrea Bocelli would be singing in the church during their wedding and that John Legend would be playing the piano at their ceremony. With the celebrations set to last four days, Alexander had her dress designer make four different gowns.

Their guest list, Alexander said, included Elton John, the Beckhams, the Obamas, the Clintons and Russell Crowe.

But as the wedding planning continued, Alexander's fiancé became increasingly embroiled in work-related issues. She said that in November 2014, they had planned a trip to California to spend Thanksgiving with her family, "and he had been really stressed in the weeks before, and he had been talking to me for some time about how there were people that were against him, and his 'enemies.'"

Then, one morning, she read in The New York Times that Macchiarini's colleagues at the Karolinska Institute had accused him of scientific misconduct and filed a complaint with the university.

The Korean girl that had undergone Macchiarini's procedure in Illinois, whose story Alexander had been sent to cover, had died in the time following the surgery. Alexander, who said she'd become close to the girl's family, was "devastated," and that Macchiarini was "depressed" about it, as they both had become attached to her.

Macchiarini denied the accusations coming from his colleagues at the Karolinska Institute to Alexander, and she doubled down on supporting Macchiarini,

Before their wedding, the couple visited Italy, where Alexander asked Macchiarini to show her where their wedding celebrations would take place. But, she said he was in a "foul mood" the entire time they were there as he dealt with the continuing fallout from the allegations.

Paolo Macchiarini is exposed

Reality struck Alexander's fantasy romance eight weeks before she was supposed to marry Macchiarini in 2015, when she received an email from a colleague with the subject line saying, "The Pope."

Her colleague had sent an article that said the pope would not be in Rome, or even Italy, on the day of their wedding. It said he'd be in South America and that the "trip had been planned for quite some time," Alexander said.

After she called Macchiarini, furious about what she'd read, she began to wonder what else he might have lied about. She said she called the castle where all the guests were supposed to be staying and asked them about the reservation, which they didn't have. When she continued to press Macchiarini about the pope, she said he blamed Vatican politics, alleging that the more conservative former Pope Benedict went behind Pope Francis' back to stop him from officiating the wedding.

Meanwhile, the investigation into Macchiarini's professional life was ramping up -- the Karolinska Institute was investigating whether he'd fabricated aspects of his medical research.

Alexander felt compelled to cancel the wedding, yet while she tried to figure out the extent to which Macchiarini had lied, she said she let him think they would still marry one day.

"I made a very strategic decision to start playing a cat-and-mouse game, basically," she said. "I wanted to get all the information that I could … before I really confronted him."

During her investigation into Macchiarini, Alexander hired private investigators in the U.S. and Italy. She was able to get the Vatican to verify that he had never been the pope's personal doctor. A contact she had to the Clintons told her they'd never heard of Macchiarini. There was no evidence the Obamas had heard of him, either.

Moreover, the Italian investigator found records showing that despite planning a wedding with Alexander for so long, Macchiarini was still legally married.

By the time Alexander discovered these things about Macchiarini, she said she'd spent over $50,000 on wedding preparations and quit her job.

On what was supposed to be the day of her wedding, Alexander flew to Rome, where she eventually met others who'd kept their travel plans. After a few days there, she traveled to Macchiarini's home in Barcelona, Spain, with some friends who came along for support.

Macchiarini had told Alexander that he was on a work trip in Russia, but when Alexander pulled up near his home, she said he was standing on the steps with his dog.

"I was angry as hell. … I see a woman and two kids," she said, adding that she knew about Paolo's wife in Italy. "The woman in Barcelona was not his wife."

Alexander, who waited in the car, said that the last time she saw Macchiarini, he had turned around and walked back up the stairs. She said she later sent a lengthy text message to him, and received a single-word response: "Wow!"

Heartbroken, Alexander continued to discover more of Macchiarini's lies in the ensuing months. She reflected on their relationship and wondered how she could've missed all the red flags. She said one question was heavy on her mind: "Why did you do this to me, why would you do that to anybody?"

"As devastated as I was and as much as I wanted to crawl under the covers and hide and stay there, I knew I couldn't fall apart," she said. "I couldn't fall apart because I am a single mother with a daughter who needs me. I couldn't fall apart because if he's lying to me like this, there's no way he's not lying in his medical and professional life."

The accusations against Paolo Macchiarini

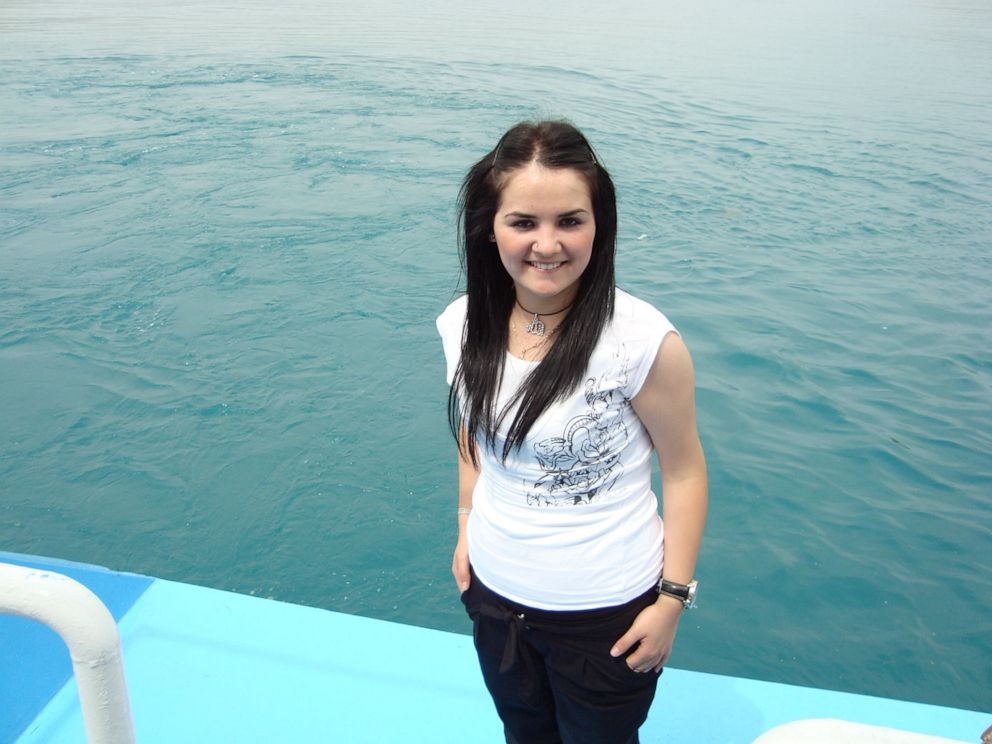

In 2015, Alexander sent emails to the Karolinska Institute expressing concerns about the acclaimed surgeon. Macchiarini was already being scrutinized for his work, including by doctors who had been trying to save the life of one of his patients, Yesim Cetir.

Cetir came to Macchiarini's attention after undergoing an elective procedure to correct a condition that caused excessive sweating. In the course of that operation, the surgeons had nicked her trachea.

"The surgeons in Turkey tried to repair it and there were some complications," said Rosemary Pinto, a personal injury lawyer later hired by Cetir's family. "She was having problems with infections so, at that point, she came into contact with Dr. Macchiarini."

By the time he performed the artificial trachea transplant on Cetir, he had already performed the same procedure on four other patients.

After Cetir's surgery, doctors say she had to undergo an additional 191 surgeries for other complications.

"She had suffered at least two strokes; she had lost much of her vision, so she was partially blind; she couldn't walk," Pinto said.

"We had to clear her throat basically every four to six hours, sort of 24 hours, seven days a week," said Oscar Simonson, a cardiothoracic surgeon who worked at the Karolinska Institute and its affiliated hospital at the time.

Mathias Corbascio, another cardiothoracic surgeon who worked at the Karolinska Institute at the time, said the intensive care unit doctor responsible for her care began consulting with him on the literature written by Macchiarini on tracheal replacements.

The group eventually grew into four doctors, who compared the journal reports Macchiarini had published about his procedure -- all of which reported relatively positive results -- to the actual medical records of those patients.

"When I started reading specifically the papers that Paolo himself had written, then we could quite quickly come to the conclusion that what was written in the papers was not what was going on … in reality," Corbascio said.

While still trying to care for Cetir, Corbascio said his team found that Macchiarini had exaggerated the effectiveness of his surgeries and falsified data to make the surgeries seem more successful than they were.

Macchiarini had reported that after his first patient underwent the procedure, a healthy trachea was beginning to develop, Lindquist said. But the biopsies showed the cells were dead and that there was actually fungi growing on the plastic, he said.

"It said that he had a normal functioning airway," Corbascio said. "That wasn't true. … They said that the patient was doing fine and that's not true: One of his lungs was completely obliterated from a chronic infection."

The doctors also raised the issue that Macchiarini had reported on a patient in a way that suggested the patient was still alive, even though they had died before the paper was published.

"The first thing we did was inform our boss, and then we also informed Paolo Macchiarini's bosses at the university," Corbascio said.

In a 500-page complaint filed in 2014 that detailed their allegations, the doctors accused Macchiarini of promoting a medical procedure that showed few signs of success while endangering the lives of his patients.

The Karolinska Institute commissioned an external investigation into the allegations. It hired Bengt Gerdin, a professor at Uppsala University in Sweden, who spent six months examining some of Macchiarini's papers for evidence of research misconduct and in May 2015 determined that he was guilty, writing in his report that Macchiarini had made false claims about his patients' conditions improving, failed to report severe complications in some patients and made it seem as if some patients had been healthier for longer than they'd actually been following their surgeries.

Gerdin also said Macchiarini had failed to obtain ethical permits to perform the transplants, which he said amounted to experimentation on human subjects.

In response to Gerdin's report, Macchiarini denied all the findings.

Three months later, the Karolinska Institute ruled that while Macchiarini did not always rise to the level of its standards, he had not committed scientific misconduct. Corbascio called the decision "absolutely insane."

Meanwhile, the doctors were still trying to save Cetir's life. She'd been in the intensive care unit in Turkey for three years, and her health was still deteriorating. In need of a lung transplant, doctors arranged to transfer her to Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia.

As these events were unfolding, Maccharini allowed Lindquist to follow him for a documentary film. Lindquist had begun his own investigation into the claims brought forth by Macchiarini's colleagues.

All of this was happening around the same time that Alexander was preparing to share her own story publicly for the first time in a Vanity Fair article.

The article's author, journalist Adam Ciralsky, had also uncovered fabrications in Macchiarini's professional life, and he documented a number of examples of Macchiarini misrepresenting his medical training and work history.

"I talked to my editors and we started thinking, 'Well, let's just keep pulling on this thread. ... I did not think that by pulling that thread, we would completely undo the sweater."

Lindquist's three-part documentary series "The Experiments" began airing just over a week after the damning Vanity Fair article was published in early January 2016.

"The Experiments" told the stories of some of Maccharini's patients, including young mother Julia Tuulik, who damaged her trachea in a car accident. Although her family said the injury wasn't serious enough to necessitate a tracheal transplant, she still underwent the procedure and went on to experience tremendous pain. Eventually, she died.

Macchiarini claims the synthetic trachea didn't shorten Tuulik's life or the lives of any of his other patients, or cause their deaths. Instead, he says their underlying health conditions were fatal and may have been a factor in their deaths.

Lindquist said the documentary sparked outrage in Sweden, and weeks later, new investigations into Macchiarini began.

"The outcry was such that the Karolinska Institute had to do something," said Ritchie.

The Karolinska Institute, which had renewed Macchiarini's contract in November 2015, launched another investigation into Macchiarini and reversed its previous conclusions -- Macchiarini was indeed guilty of scientific misconduct, the Institute determined. His six papers on the transplant surgery were retracted.

The university even cited some of the whistleblowers, reprimanding them for their participation in some of Macchiarini's papers.

Ole Petter Ottersen, president of the Karolinska Institute since 2017, told ABC News in a request for comment on Macchiarini, "It is obvious that KI's initial handling of this case was insufficient and inadequate on several points. It has led to extensive reform work internally at KI in order to improve and clarify a number of regulations and routines."

He also directed ABC News to a list of reforms the Institute was implementing in the wake of the scandal.

While Macchiarini continued to deny any wrongdoing, he lost his job at the Institute and Swedish prosecutors began looking into whether his behavior was criminal.

Of the eight patients given artificial tracheas by Macchiarini, only one is still alive today. He's also had his artificial trachea removed.

Cetir died waiting for the lung transplant she desperately needed.

Cetir's family has filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the manufacturer of the plastic tube used in Macchiarini's procedure.

In September 2020, Swedish prosecutors announced charges against Macchiarini for aggravated assault in connection to three surgeries that he had performed at the Karolinska University Hospital, including Cetir's. Macchiarini has not yet entered a plea, but has denied all of the charges. Hearings are expected to begin in 2022.

Macchiarini did not respond to a request for comment from ABC News. He's also never spoken publicly about his relationship with Alexander.

"I want him to go to trial… I want him to look around that courtroom and see the families of the patients whose lives he destroyed, and see my face and at last be forced for whatever few seconds … to look us all in the eye and maybe understand what he did," Alexander said. "And then I want him to be held accountable. I think he needs to be behind bars."