'Stanford murders' conviction renews hope for justice in 2nd alleged victim's cold case

On March 25, 1974, truck driver Ernesto Evangelo spotted something unusual on his morning milk delivery route near the Stanford Dish, a massive radio antenna close to the Stanford University campus.

He pulled over and discovered the lifeless body of a woman in a shallow ditch.

It was Janet Taylor, a 21-year-old college sophomore and the daughter of legendary Stanford athletic director, Chuck Taylor. She had been beaten, strangled and left on the side of the road, according to authorities. Her feet were bare and dry despite the wet ground beneath her.

Taylor, a student at nearby Canada College, was last seen by her best friend Debbie Adams on the Stanford campus the night before. Her car was in the shop, so Taylor went home on foot, according to Adams' testimony. She was anxious to get there to feed her puppy, Adams said, so she resolved to hitchhike. Neither Taylor nor her friend feared for her safety, according to Adams, but that was starting to change.

As female empowerment was on the rise, young women hitchhiking alone in the 1970s was a normal occurrence, especially in idyllic Northern California.

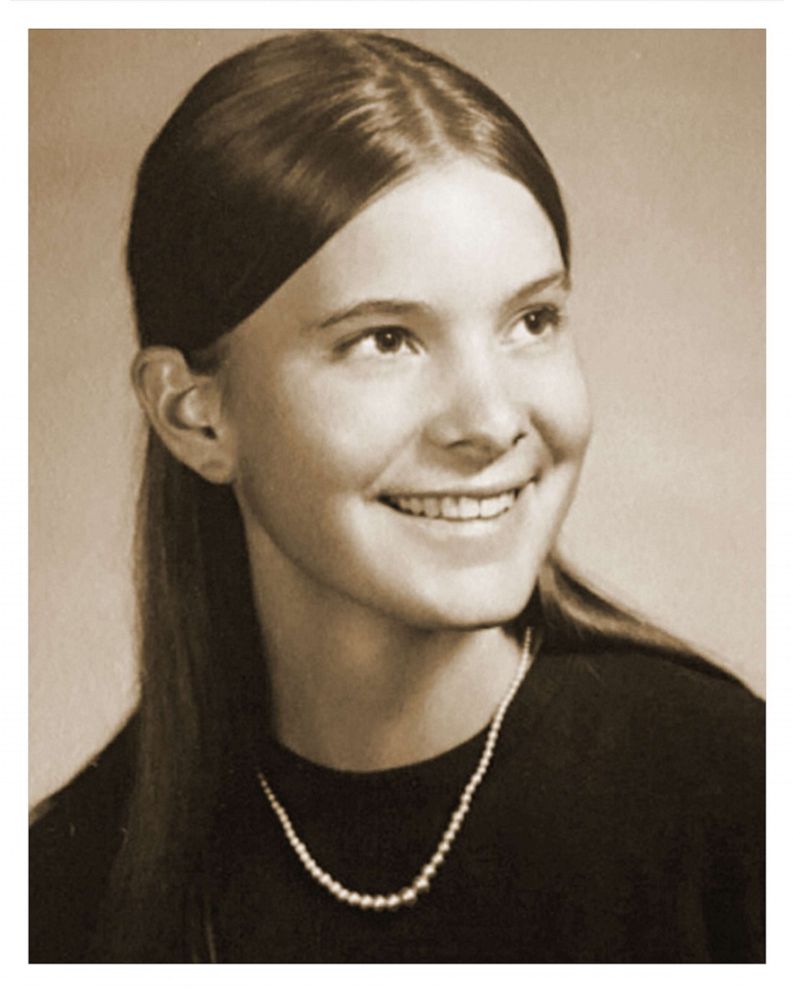

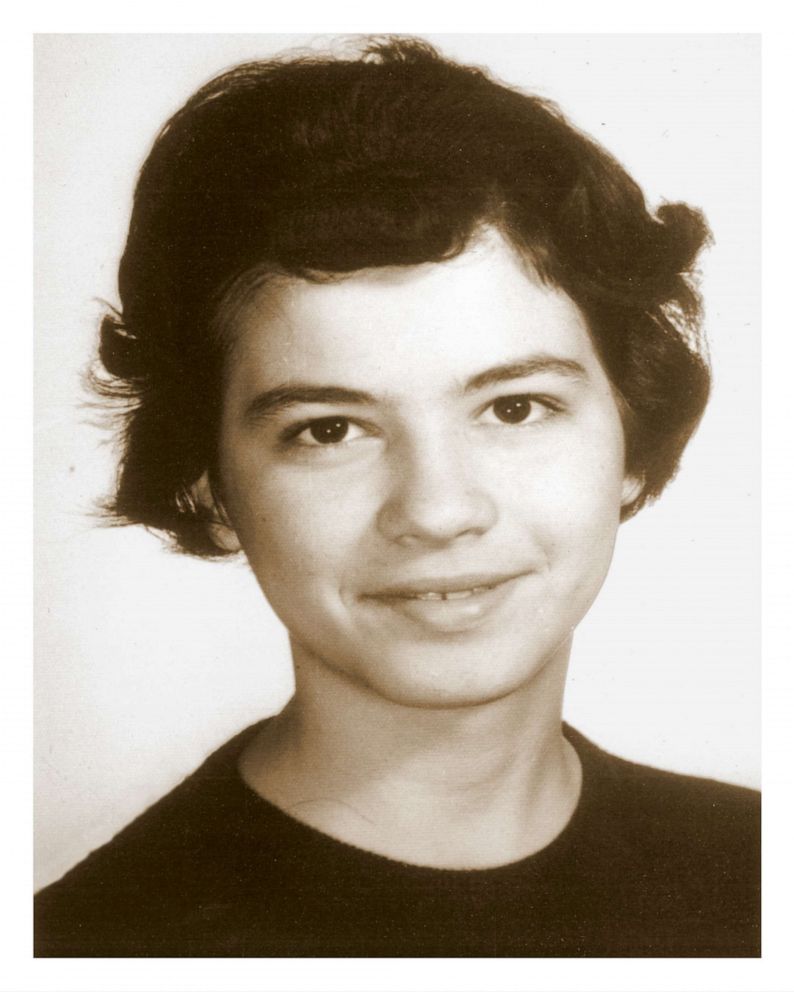

But just a year earlier, on Feb. 13, 1973, Stanford honors graduate Leslie Perlov, 21, called her mother from the law library to tell her she was driving home, which was a short jaunt from the Stanford campus. She never made it.

The next day, search parties found Perlov's body near her abandoned car, about a mile from where Taylor’s body would be found the following year. Similar to Taylor, Perlov also appeared to have been viciously assaulted and strangled. Her body bore telltale signs of a prolonged brutal torture, according to Santa Clara County coroner Dr. Richard Mason. Perlov had been beaten so badly both her eyes were swollen shut, her nose broken and her underwear and stockings had been shoved down her throat.

Despite similarities between the two killings, investigators at the time could not link the crimes.

Without credible leads, the university community was steeped in the fear that a serial killer was roaming free and actively stalking young women.

As years passed, then decades, both cases went cold. The mystery became known as "the Stanford murders."

For nearly 50 years, the families of Leslie Perlov and Janet Taylor waited for justice, until now.

Watch the full story on "20/20" FRIDAY at 9 p.m. ET on ABC

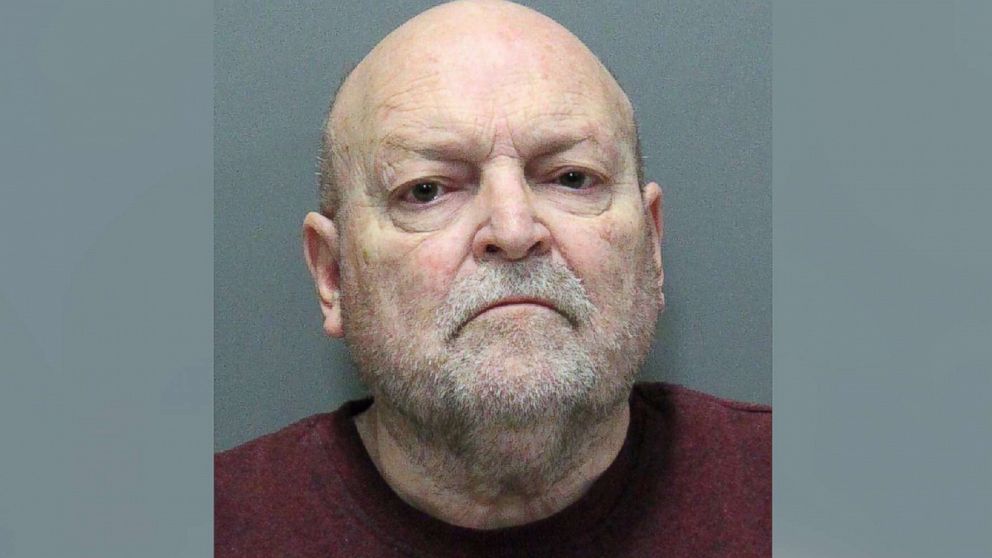

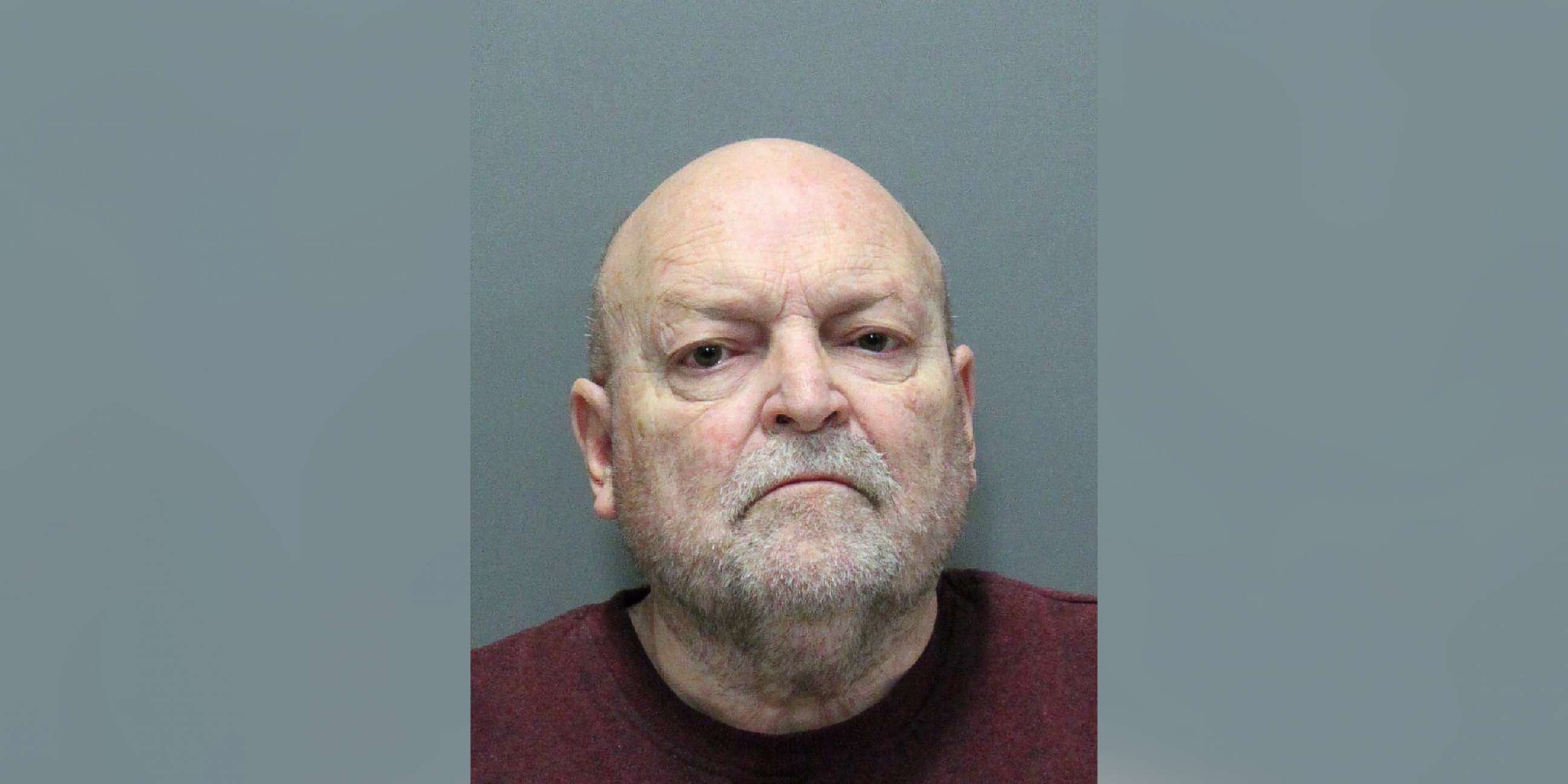

On Tuesday, after a little more than an hour of deliberation, a San Mateo County, California, jury found 77-year-old John Arthur Getreu, a former Stanford employee, guilty of first-degree murder and infliction of great bodily harm in Taylor's death.

Getreu is expected to be sentenced on Nov. 3 and could face 25 years to life in prison.

His defense attorney John Halley had no comment for this report.

Advancements in DNA technology played a critical role in Getreu's conviction for Taylor’s murder and renews the possibility of justice for Perlov's family.

Getreu is scheduled to stand trial for Perlov's death in neighboring county Santa Clara next year. As he did in the Taylor case, Getreu has pleaded not guilty in the Perlov case.

But with Getreu in ill health and the COVID-19 pandemic backlog at court, a trial may never happen.

“This is not the end," Perlov's sister Diane Perlov said. "We are moving forward. I want a trial for my sister’s case. I don’t want any deals. There were some really horrible photographs of what Getreu did to Janet and what he did to Leslie and I want everyone to see them so they understand what a dangerous person he is."

DNA reveals prime suspect

The Perlov case was reexamined in 2016, and newly tested forensic evidence from Perlov’s fingernails led to Getreu’s arrest in November 2018.

Cold case detective Sgt. Noe Cortez was the one to have the evidence tested.

“It was a brutal crime... I believe she fought for her life. And part of that was scratching, biting whatever she had to do to survive,” Cortez said. “She wanted to live.”

Intrigued by the popular rise of ancestry websites and the potential for discovery of incriminating genetic material, Cortez reviewed the case files and discovered that Perlov’s struggle in the last moments of her life yielded DNA from each of her 10 fingernails.

Cortez’s superior, Santa Clara County Sheriff Laurie Smith, had made solving the Stanford murders a priority when she was elected California’s first female sheriff in 1996.

“We may not have been able to get them way back when, when we didn't have DNA, but we can do it now. I believe in getting justice no matter how long it takes,” Smith said.

Cortez sent the nail clippings to a private lab. After several months, forensic scientists were able to create a genetic profile for her killer based on the abundance of DNA material.

“Parabon NanoLabs was able to develop a person of interest who they named as John Getreu,” said Cortez.

Authorities say the match Parabon Labs identified had a 1 in 65 septillion odds of being inaccurate.

Cortez learned that Getreu was a former Stanford University technician with a dark history of rape and murder, who still lived in the Bay Area.

A sting operation was conducted to collect Getreu’s DNA from a discarded cup. Cortez and his partner followed Getreu and his current wife, who is also a Stanford graduate, to a coffee shop. Authorities say the DNA from that cup was an identical match for the Perlov case and for DNA collected from Taylor's green corduroy pants by San Mateo criminologist Alice Hilker.

Getreu’s history of violence

Evan Williams, a retired pastor now living in Tennessee, said he contacted the FBI about Getreu years before his 2018 arrest.

Getreu had been convicted of murdering Williams’ sister in Germany, but moved back to the United States afterwards, and Williams thought he would kill again.

“I'm calling to let you know about a man in California who has committed murder that you probably have no idea about. And the reason I know about this man is he killed my sister in 1963,” Williams remembered telling them.

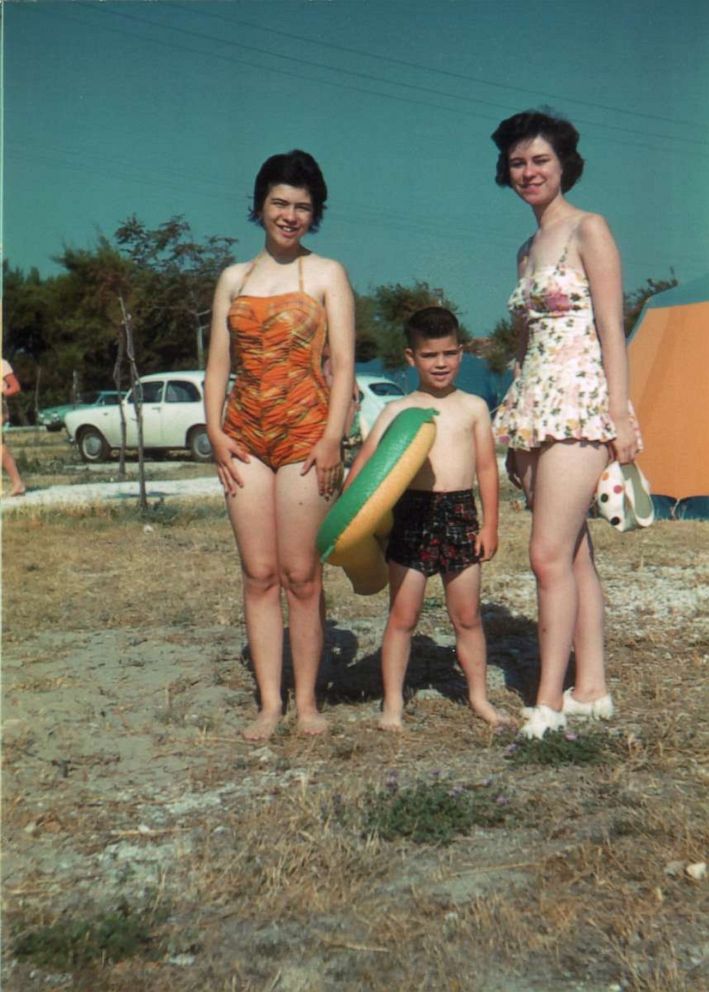

Getreu was 18 when he was convicted of raping and murdering 15-year-old Margaret Williams after offering to walk her home from a dance on a military base in Bad Kreuznach, Germany. Margaret was the youngest daughter of the U.S. Army Chaplain and Evan Williams’ older sister and best friend.

“My sister Margaret, as a young child, brought a lot of joy to our family. She was a very caring kind of person. And when my sister died, some of the joy of the family was stolen,” Williams said.

One night, following an afterschool gathering that ended at 10:30 p.m., Williams’ parents were expecting their daughter home by 11 p.m.

“In something my father wrote, he was talking about how it started raining. So he drove to the youth activities building and he found out she had left five minutes before he got there,” Williams said. “When she didn't arrive home, he hoped that she had just stopped because of the rain and then would be coming along soon. But then when she did not arrive by midnight, they called authorities and said, our daughter always shows up for curfew and she's not home. Her body was found, I think at 1:11 a.m.”

Evan Williams’ other sister Marianne Stowers said the whole family was incredibly shaken by the violent loss.

“My mother never wanted to see my sister’s dead body at all. So we had a closed casket,” Stowers said. “For a real long time after that, I still couldn’t believe my sister was dead. I was looking for her everywhere I went. I expected to see her.”

Getreu was convicted in German courts as a juvenile in 1964.

“That meant that he would end up with a shorter sentence and he would also be in juvenile detention,” Evan Williams said.

The maximum sentence at the time for a juvenile was 10 years for homicide. Getreu only served six years and was released on March 7, 1969. The country ordered him to leave Germany within 24 hours of his release.

“They released him one day and he was on a plane the next day to the United States,” Evan Williams said. “It's kind of like Germany going, ‘Okay. It's out of our hands.’”

The thought of Getreu living freely began to really “nag him,” Williams said. He started to do some research online.

“I was able to look up his name, I knew his age, and I found that he was a resident in California. That got my attention and made me think he could potentially be the Golden State Killer,” Williams said.

The so-called “Golden State Killer” was Joseph DeAngelo, who was a police officer from 1973 to 1979. He terrorized several areas of California around the same time Perlov and Taylor were killed, committing multiple murders and rapes in the 1970s and ‘80s.

That case also remained unsolved until DNA evidence linked DeAngelo to several of those crimes and he was arrested in 2018.

In June 2020, DeAngelo pleaded guilty to 13 counts of first-degree murder as part of a plea deal, which also required him to admit to multiple uncharged acts, including rapes.

Even still, Williams wondered if Getreu had gone on to commit other violent crimes over the years.

“I thought because of the particulars of what had happened with my sister, that he would commit more violent crimes,” he said.

The stepfather

In 1970, less than a year after his release from prison in Germany, Getreu had a job at a California hospital.

He married one of his coworkers, Susan, a single mother with a daughter named Cathi.

Susan and John Getreu were married for eight years and lived on and off in Palo Alto near the Stanford campus.

John Getreu was a Boy Scout leader who appeared to everyone else to be a loving husband and stepfather, but Cathi, now 58, says she knew her stepfather to be a monster.

She claims Getreu molested her from when she was 6 years old until she was 14.

“Basically, [he] makes me touch him and tells me that if I tell anyone he will hurt my mother,” she said. “And I believed every word he said because he made it very clear to me he had that power.”

Cathi said she never told anyone because she was afraid of what Getreu might do.

“The only thing that was going to save me from him was his death,” she said. “And that was the only way I ever thought that it would stop.”

The marriage came to an abrupt end in 1977 after Susan said she caught him molesting her daughter.

“The day my mom walked in on John Getreu performing oral on me, probably the most uncomfortable, horrible experience of my entire life but at the same time was the best day of my life because finally my mom knew what was happening and she would stop it,” Cathi said.

“I didn't know what to do,” Susan added. “I was beside myself, and to just think that somebody would do this to a child, just appalled me.”

Susan never filed charges against her ex-husband and John Getreu has not been charged in relation to Cathi though both Susan and Cathi testified against him at trial last week.

When asked if John Getreu denied these physical and sexual abuse claims, his defense attorney had no comment.

John Getreu’s new family

In October 1978, just months after Susan divorced him, John Getreu married his second wife, Lynda Caputo, who died in 2002. They had two children including a son, Aaron Getreu, who remembers him as a “loving father.”

“[There was] never any indication he could have done anything like what he's being accused of,” Aaron Getreu said.

In the first public remarks since his father’s arrest in 2018, John Getreu’s only son said the man described by prosecutors at Getreu’s murder trial as a serial rapist and killer is not the man he knows.

He said he knew his father as the baseball and soccer coach, someone who taught him to treat women with respect.

“I grew up in a loving household,” Aaron Getreu said. “He was a big part of our lives.”

Aaron Getreu said he and his wife were shocked when they received the call in November 2018 that his father had been arrested for murder.

“At first I thought this must be some kind of joke,” he said. “It was very shocking because that’s not my dad. It was like your whole world stopped.”

What's next for John Getreu?

With Getreu’s trial for Taylor’s murder behind them, Leslie Perlov’s younger sister Diane Perlov is undeterred in her quest for justice. She is looking ahead to when Getreu goes on trial for her sister’s murder next year.

Leslie Perlov, an academic standout, was headed to University of Pennsylvania Law School when she was found dead in 1973. She was killed just months after the family lost their father to cancer.

“[This week] was justice for Janet, Leslie, Diane and Margaret," Perlov said. "While these promising lives are gone forever, thanks to the dogged work of detectives and the advances in forensic science, I have hope that future lives will be saved and other predators held accountable”

Aaron Getreu said he is now on a crusade to find out if his father could be connected to other crimes, trying to make something good happen out of all this “evil.”

He reached out to Evan Williams and over the course of the two years they have developed a close bond.

After Williams testified at John Getreu’s trial, Aaron Getreu hugged him.

“Welcome to the club, Aaron,” Williams told him. “It’s a small club and no one ever wants to be a part of it but we are all victims of John Getreu.”

Aaron Getreu said he has refused to speak to his father since his 2018 arrest, but urged him to come forward and reveal if he has committed more crimes.

“[My dad] needs to come out and tell the truth,” Aaron Getreu said. “DNA does not lie.”

Grace Kahng is an investigative journalist, Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker and director of "The Stanford Murders." Learn more at stanfordmurders.com.