South Korea, North Korea prepare for historic summit

GOYANG, South Korea -- South and North Korea are bracing for a historic summit between its leaders Friday, with high hopes of setting the stage for a peaceful coexistence.

But both nations are wary of how the results may affect the proposed subsequent meeting planned between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, an encounter the United States has said is tentatively planned for late May or early June.

Seoul is confident that this third-ever summit between the two Koreas will lead to a complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization on the Korean peninsula. But skeptics doubt that's what the North intends.

To Kim’s credit, he declared a "new strategic line" last week to focus on economic development, claiming that because he's achieved "victory" in becoming a nuclear power, North Korea is ready to take its share of responsibility to denuclearize.

Kim took the first step, even before his scheduled summits with South Korean President Moon Jae-in and Trump, by announcing the North will suspend nuclear and missile tests and shut down its Poongyeri nuclear test site.

The sudden turn of events, after nearly reaching the brink of war last year, has many wondering what North Korea wants in return for its pragmatic approach now.

Those answers may become clear, at least to some extent, on Friday as millions around the world watch the summit broadcast live.

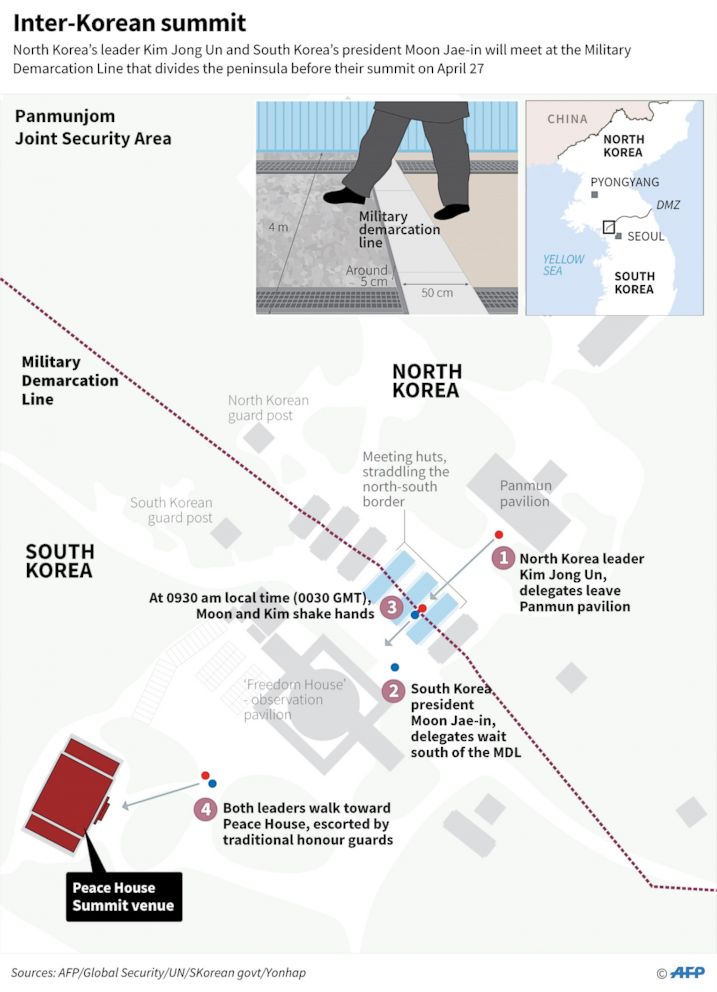

Kim and his entourage are scheduled to walk across the military demarcation line to step foot on South Korean soil and to meet Moon around 9:30 a.m. local time.

Honor guards will escort the two leaders to a welcome ceremony at the truce village of Panmunjom.

The summit will take place in the morning and afternoon inside the Peace House at the southern side of the DMZ with separate luncheons and a short ceremony to plant a "commemorative pine tree as an expression of wishes for peace and prosperity," Im Jong-seok, South Korea's presidential chief of staff, said at a news briefing.

The declaration of mutual agreement will be announced in the afternoon, followed by a dinner banquet carefully prepared to reflect wishes for peace and prosperity.

It is still undecided whether Kim's wife, Ri Sol-ju, will attend the banquet, Im said.

For Kim, it is a risk to step outside his isolated country and away from the state-controlled media that worships him. Journalists from around the globe will report on his every move and analyze his every word.

"This is the big event where Kim Jong Un is truly making a grand debut to the international community," said Yun Keol Lee, chief of the North Korea Strategic Information Service Center, a private research group in the South.

The success, or failure, of the high-stakes talks could determine the fate of the Korean Peninsula. Here's what to watch for:

Denuclearization

Debate lingers over what exactly "denuclearization" means to North Korea compared with how it's viewed in the U.S.

The big question is: How much is Kim willing to give up?

Some analysts have said the North's nuclear program is already too advanced and scrapping it completely isn't realistic.

South Korea has repeatedly hinted that Kim is willing to go for a complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization, or CVID.

Skeptics doubt Kim's intentions given his nation's track record of breaking its promises.

"North Korea will never give up the nukes,” said Lee Young Jong, director of the Unification Research Institute at South Korea's JoongAng Ilbo newspaper, describing how Pyongyang has long believed that only military force, especially nuclear weapons, could protect it from external threats.

To North Koreans, "there is no such thing as a complete denuclearization," Jong added.

What Kim actually declared in a report to the Workers Party of Korea last week is murky, and interpretations may be worlds apart. Kim said his country would halt nuclear and ICBM testing because it's already achieved development goals.

But at the same time, the report noted the North Korean arsenal is a "powerful treasured sword for defending peace" and a "firm guarantee" for future generations to "enjoy the most dignified and happiest life in the world."

In other words, he will keep the arsenal as insurance.

"The language is carefully calculated, just enough to keep the momentum going for talks without pledging to give up the nuclear weapons," Shin Beom Chul, a professor at the Korea Diplomatic Academy -- part of the South's Ministry of Foreign Affairs -- and senior fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, a think tank in Seoul, told ABC News.

Even if the two leaders agree on the basic idea of disarmament, most analysts believe frictions will occur in the process of laying out details on how and by when denuclearization would be carried out.

"North pulled the wool over our eyes to buy time for further nuclear experiment. This time, we should not repeat our past mistakes," said Shin Kak-soo, South Korea’s former ambassador to Japan.

"North Korea is deftly maneuvering the global community to show off Kim’s big influence internationally and domestically and in a way to appear as if the North is recognized as a nuclear-armed nation," Yun added.

The Moon administration admits the difficulties of stipulating Pyongyang's will to denuclearize. Even if there is a clear, mutual agreement, to what extent the two Koreas will go to guarantee "complete" denuclearization is up to the two heads of state to finalize, Im said.

Securing permanent peace

In return for a pledge to relinquish its nuclear program, North Korea wants two things from the outside world: economic assistance and a guarantee others will not seek to topple its leaders.

In what seems like an effort to ease Pyongyang’s insecurity, Moon has outlined a "spirit of mutual respect" to achieve permanent peace.

"We do not wish for North Korea's collapse, and will not work towards any kind of unification through absorption," said Moon, meaning Seoul has no intention to strike the North militarily.

North Korea is paranoid about the outside world. Many there have long believed that the U.S. intended to force a change in leadership, upending three generations of Kim rule.

To that end, Pyongyang long has insisted that U.S. troops in South Korea are a threat to its autonomy. Withdrawing those 28,000 U.S. troops has been mentioned as a longstanding precondition to talks of disarmament, an idea strongly supported by China, North Korea's strongest ally.

However, Moon told reporters last week that North Korea is not explicitly asking the U.S. to remove all of its troops from the peninsula as a precursor to denuclearize.

Many analysts don't expect a definitive announcement Friday on what will happen to the U.S. troops there.

The "troops issues should be handled at the U.S.-North Korea summit. It’s a matter of choice and decision to be made by President Trump's administration," said Joo Seung-hyun, a North Korea specialist and defector who now teaches military science at Kijeon University, in Jeonju, South Korea.

Hammering out those details is expected to take months of negotiations among high-level diplomats and officials.

Peace treaty

Also on the agenda for Friday's meeting is replacing the current armistice between South and North Korea with a formal peace agreement -- a goal long shared by both nations.

Three years of brutal warfare, with the North backed by China and the South supported by American and United Nations forces, ended in 1953 but without a formal peace treaty. Technically, the Koreas are still are war.

Such a peace treaty could involve three parties, just as the armistice did when a U.S.-led U.N. alliance assisted on behalf of South Korea, the Chinese People's Volunteer Army and the North Korean People's Army.

"North Korea did not recognize the South as a partner that could sign a ceasefire since the armistice was signed among the other three parties," Joo explained.

Then Pyongyang stepped back in 2007 to welcome the South's participation when former North Korean leader Kim Jong Il and former South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun met for the second-ever summit. The elder Kim, now deceased, had also suggested Beijing and Washington be part of the peace treaty, but those discussions never formally materialized.

Keeping that in mind, the South Korean president now is hoping to, at least, declare an end to the war with North Korea by pursuing a separate agreement and resetting bilateral relations during the summit.

"But a peace deal in the form of a treaty," former South Korean Unification Minister Jeong Se-hyun told ABC News, "will be left aside for Trump to claim credit as a prize."

ABC News’ Hakyung Kate Lee, Jaesang Lee and Jiweon Park contributed to this report.