How gun homicides could be linked to bleak outlook of the future: Study

As gun violence continues to shorten the average life expectancy of Americans, researchers have new insights into the root causes of one distressing type of death: firearm homicides.

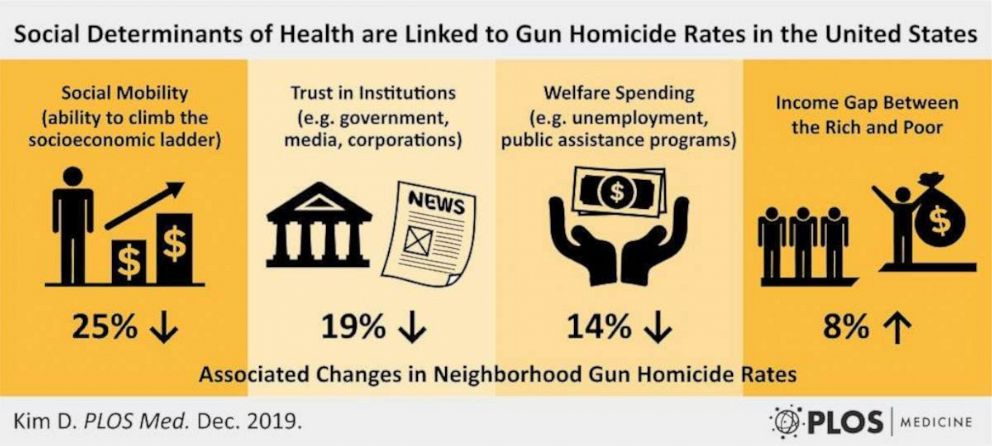

A new study, published Tuesday in the journal Plos Medicine, found that four social factors -- mobility, trust in institutions, welfare spending and income inequality -- were linked to gun homicide rates.

"We know that these root causes can be modified through policies," Dr. Daniel Kim, lead author of the study and associate professor at Northeastern University, told ABC News. "This, and future research, could get policymakers to tackle the gun violence epidemic in America."

As of 2017, gun homicides made up 14,542 of the nearly 40,000 gun deaths that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that year.

The study analyzed neighborhood firearm homicide data from 2015 and compared that to measures of four social determinants of health. Kim stressed that the link between gun homicides and social factors is an association, rather than a cause-and-effect phenomenon, and that some factors had a stronger connection than others.

The strongest association was social mobility, or children's ability to climb higher on the socioeconomic ladder than their parents. High social mobility was linked to 25% lower gun homicide rates on the neighborhood level.

"Previous studies suggest that if there's low social mobility or economic opportunity, people may feel a sense of hopelessness," Kim noted. "It can affect their psychological or emotional state."

His hypothesis: people living in communities without the hope of a more prosperous future -- and without options -- may be more likely to resort to committing crimes.

Income inequality had the smallest effect in the study. Wider gaps between rich people and poor people in a community was associated with an 8% higher gun homicide rate. Higher welfare and education spending, however, was associated with a 14% lower gun homicide rate. To a degree, these factors are intertwined.

"It's not bad people in bad neighborhoods," said Cassandra Crifasi, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research, said of gun homicides.

"These are people with inadequate access to resources," Crifasi, who was not associated with the study, told ABC News.

That unequal distribution of resources isn't an accident, Crifasi explained. Instead, it's fueled by historical policies, such as redlining, a 1930s policy in which local lenders refused loans to residents in minority neighborhoods.

The result was pockets of concentrated poverty across the country, which still exist today. According to a study published last year by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, three out of four neighborhoods that were redlined in the United States decades ago continue to struggle economically.

"Years ago, we created these environments, where we're still seeing the challenges today," Crifasi said.

Unequal policies created some of the social inequalities linked to gun homicides, and Kim hopes policies to level the playing field might be part of the solution.

He pointed to programs that make college more affordable for low-income students, as well as tax policies, such as a wealth tax, that could potentially shrink the gap between rich and poor.

While tax policies can shape income inequality, they can also be a potential driver of social mobility, he explained.

A fourth and final factor the study observed was less closely linked to economics.

Kim found that higher trust in institutions, such as the government, the media and corporations, was associated with 19% lower firearm homicide rates.

"From a political standpoint, people don't trust the government as much as they used to 10 years ago," Kim said. Not trusting higher institutions could potentially indicate a wider pattern of distrust, he hypothesized.

"It may trickle down to just not trusting people," he said. Both Kim and Crifasi pointed to previous research showing that people living in communities that didn't trust the police were more willing to take the law into their own hands.

When you feel like your needs are not being met by the institution, "it's hard to feel like you're bought in," Crifasi said.