Shark attacks: What are the most dangerous places in America? Here's your guide.

New York may have been the site of two suspected shark attacks on Wednesday, but attacks by the creatures in these waters are so rare that there have been only 10 documented cases confirmed in nearly 150 years.

The worst place in America for shark attacks? Florida. Statistics from The International Shark Attack File, a database of shark attacks from around the world, show that Florida's coast has witnessed a total of 812 confirmed and unprovoked shark attacks since 1837, at least those that have been recorded.

That's because most sharks prefer warmer waters, said George Burgess, director emeritus of the International Shark Attack File maintained by the Florida Museum of Natural History. "The waters near the East Coast, in the northern states like New York are cool for most months of the year, and so it's only in the summertime when a few sharks arrive."

Which states are more vulnerable to attacks varies widely along the American coastline. Maine has one attack on record since 1837. California has 122. But the pattern is not random, says Burgess. The more coast, the more people and the warmer the waters, the more the attacks.

Still, despite how few attacks New York's coast has seen, there are enough species of sharks in these waters to prompt a few sightings, Burgess of The International Shark Attack File said.

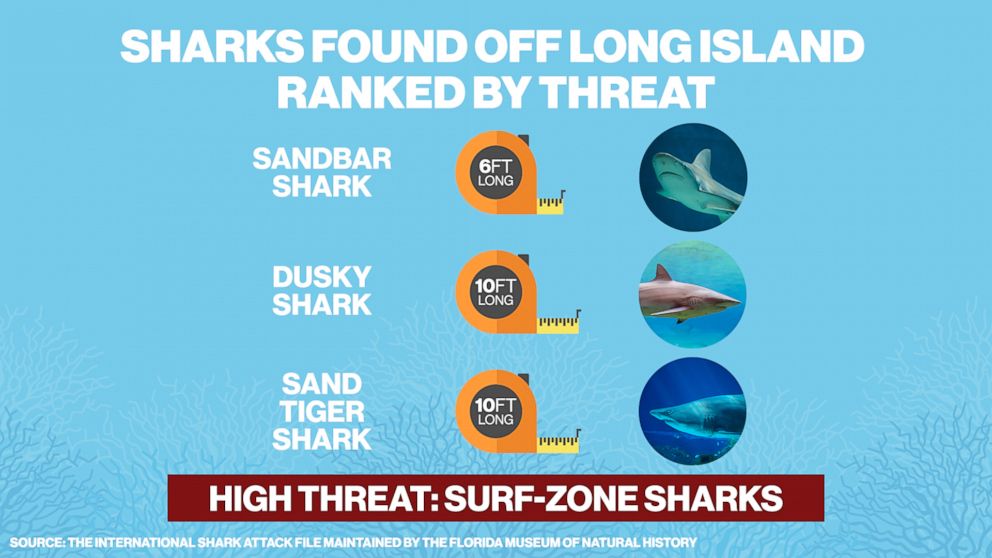

Not all of them bite humans, not all are even big enough, but here's a list of the species shark-watchers in the state are more likely to encounter, ranked by how much of a threat they are to humans.

The list is not based on the actual number of attacks these species have already carried out, because that number is too small to analyze. Instead, it's based on the potential each species has to be a threat to humans along the coats of New York.

"Almost any shark that can grow to about six feet or two metres in length is a potential danger to humans," Burgess explains. "That's only because once they get to that size their teeth are sharp and they can cause damage"

1) High Threat: The 'surf zone' sharks

The Sandbar shark (up to about 6 feet long) and the Dusky shark (up to about 10 feet long) are both species that are much more comfortable in cooler water than other species of sharks, and they like to stay in the 'surf zone' - the part of the sea next to the shore within which waves break, and where beachgoers tend to stay. The Sand Tiger shark (up to about 10 feet long) swims a little further off but still in rleatively shallow waters, where divers often come across them in wrecks.

2) Medium Threat: The offshore sharks

"The south shore of Long Island faces an ocean, and so some species that can travel a little further north sometimes wander in from deeper waters to areas where humans are," said Burgess. The first of these species is the infamous White shark, better known as the Great White shark (up to about 23 feet in length). The other is the Blue shark (up to about 12 feet in length).

3) Low threat: The vegetarian shark and the sharks that are too small

Every once in a while, a Basking shark (up to about 30 feet in length) will be seen on the coastline or will wash up on the shore, and a lot of attention will be drawn to it because of its size, said Burgess. But this species couldn't hurt humans if it wanted to. Its teeth are flattened due to a sort of a plate-like surface, as it only feeds on plankton, and it is not at all aggressive, said Burgess. On the other end of the spectrum, the Spiny Dogfish shark (up to about 3 feet long) and the Smooth Dogfish shark (up to about 4 feet long) are both species that love cool waters, but are too small to cause any harm to humans.

But despite the existence of these species of sharks in the waters near New York, Burgess points out that relatively speaking, there's very little to fear. For example, between 1959 and 2010, there were three shark attacks in New York. All three of the victims survived. In comparison, there were 139 people who died due to lightning strikes.

Even if a shark were to attack a human, it's usually because they mistook the human for a fish, and they let go immediately, Burgess said.

"The shark interprets the kicking and walking movements of the human body in the water to be activities of a normal prey item," he said. "And of course in the surf zone, where visibility is poor as a result of the breaking waves, it will bite at things it can't see well. But it's usually just one quick bite and then it's gone, and so we call these hit-and-run attacks."