What is the Senate filibuster? And why the calls to change it?

With the issue of voting rights and election reform heating up in the wake of the Jan. 6 Capitol attack anniversary and ahead of the 2022 midterms, Democrats are looking to change a Senate rule in order to pass legislation they say is vital to preserving American democracy.

Republicans, meanwhile, have warned even a single exception to the Senate 60-vote threshold to advance legislation -- a rule known as the filibuster -- would be dangerous to democracy and the rights of whichever party is in the minority (although both parties have used the so-called "nuclear option" in the last decade -- requiring 51 votes to confirm all executive branch and judicial nominees, for example).

With Senate Republicans using the filibuster to block two key voting bills -- the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act -- a top priority for Democrats and President Joe Biden remains stalled in an evenly split 50-50 Senate.

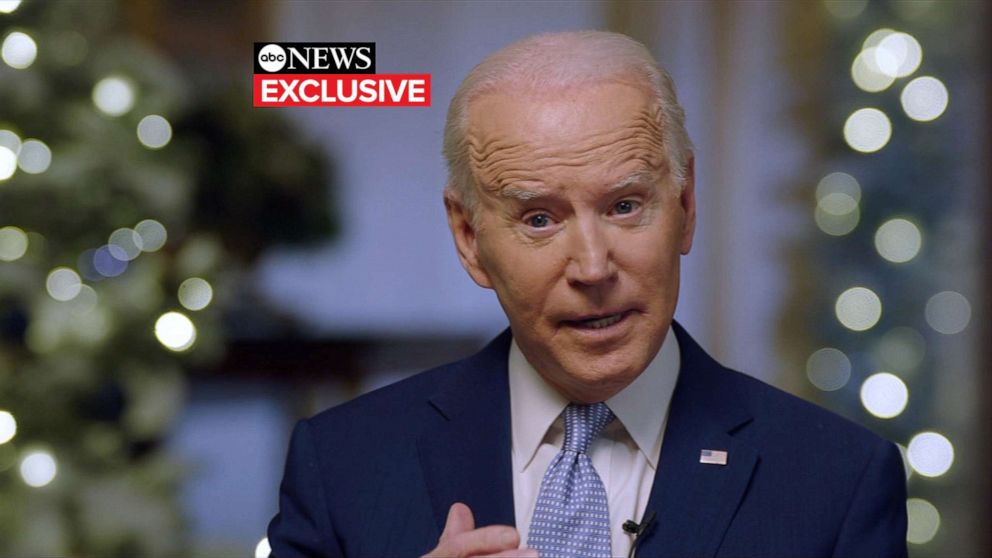

While Biden, having served in Congress for 36 years, has defended the filibuster, he told ABC News "World News Tonight" Anchor David Muir in an interview last month that he supports making an exception for voting rights, an argument he's expected to press in Georgia on Tuesday as Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer looks to a vote on changing the rule within days.

Both parties have toyed with the idea of eliminating the filibuster over the years to make it easier for the majority party to achieve its priorities. Here's what to know about the filibuster:

What is the filibuster?

The filibuster is a 19th-century procedural rule in the Senate that allows any one senator to block or delay action on a bill or other matter by extending debate.

While a final vote in the Senate requires a simple majority of 51 votes, a supermajority, or 60 votes, is needed to start or end debate on legislation so it can proceed to a final vote.

Therefore, even if a party has a slim majority in the Senate, it still needs a supermajority to even move forward with legislation -- a tall task for a hyper-partisan Washington.

The House of Representatives does not use the filibuster. Instead, a simple majority can end debate.

How to end a filibuster?

Senate rules allow for debate to continue without end until three-fifths of the chamber -- or 60 out of 100 senators -- votes to end the filibuster.

Only when at least 60 senators vote to bring debate to a close can the Senate move forward with consideration of a measure and, eventually, final votes.

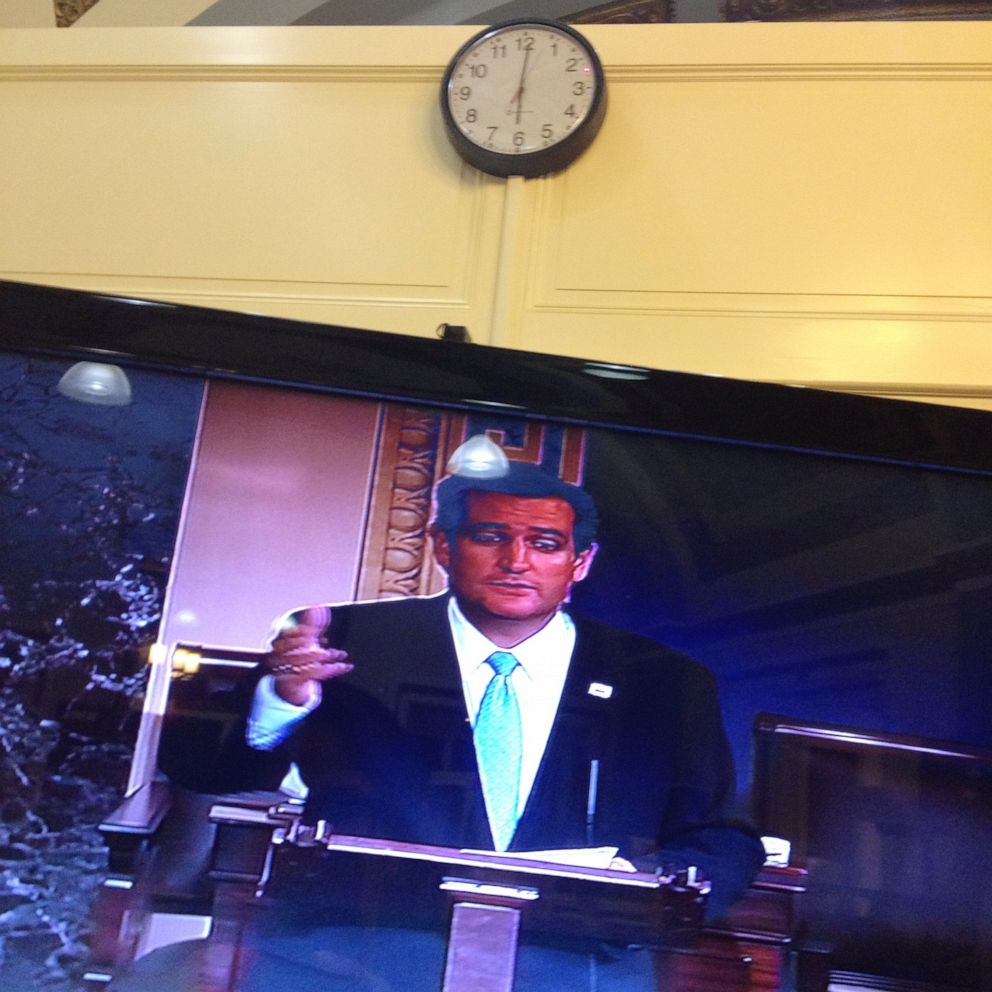

To that end, senators have stood for hours talking on the floor with the intention of blocking something from moving forward.

The record for the longest filibuster is held by Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina who spoke for 24 hours and 18 minutes in opposition to the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

In recent decades, a senator merely signaling his or her intent to filibuster a piece of legislation has been enough to stop action on a bill. Leaders, knowing the legislation lacks the support of 60 senators, might drop the issue from consideration and move on to other matters in the meantime.

How did the filibuster come about?

In 1806, then-Vice President Aaron Burr led the charge to eliminate a Senate rule, similar to one seen in the House, that could be used to cut off debate, inadvertently allowing lawmakers unlimited debate to delay proceedings.

In the 1840s, Democratic Sen. John Calhoun exploited this loophole by talking for hours on end to block bills he feared would diminish the power of Southern slave-holding states.

The Senate rule has changed several times since to make it easier for the minority to overcome a filibuster.

In 1917, at the urging of Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, the Senate adopted Rule XXII that made it possible to break a filibuster with a two-thirds vote -- known as a cloture vote.

In 1972, Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, D-Mont., introduced the "two-track" system in which the Senate can set aside a filibustered bill and move on to other business, subsequently eliminating the incentive for a senator to stay on the floor and argue their point. This prompted lawmakers to filibuster even more, since all a senator had to do then was make his or her intent to block a bill known to leadership.

Then, a rule change in 1975 made it slightly easier for the majority to end a filibuster, requiring the modern-day three-fifths of all senators duly chosen and sworn, or 60 senators, of the 100-member chamber, instead of two-thirds.

Since 1917, there have been more than 2,000 filibusters, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Nearly half have been in just the last 12 years.

How can the filibuster rule be changed?

Senators have carved out exceptions to the filibuster rule before.

One option to do so is called "going nuclear" -- when senators override an existing rule, such as the number of votes needed to end debate. This is usually done by lowering the threshold needed to end a filibuster to 50 votes.

In 2012, then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., carved out an exception to lower the threshold to a simple majority 51 votes to confirm then-President Barack Obama's judicial nominees. (It could be less than 51 if 100 aren’t present to vote.)

A few years later, in 2017, then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., eliminated the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees, clearing the way for then-President Donald Trump's first nominee to be confirmed.

Many warn that, if the filibuster is eliminated, the party in power will be able to govern without regard for the minority, setting a dangerous precedent for a deliberative democracy.

Why a call for change now?

In the last 50 years, the filibuster has been used more and more to kill major legislation. And with Biden's agenda stalled, Democrats are calling for a carveout to pass voting rights legislation. In the last year, at least 19 states passed 34 laws restricting access to voting, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

If the threshold to end debate on a bill is lowered to 50 votes, for instance, Democrats could end debate on their voting reform bill and eventually move to a final vote, with Vice President Kamala Harris serving as a tie-breaking vote in the 50-50 Senate to pass the legislation. Incidentally, Harris, as president of the Senate, would play a key role in any potential rules change. She would be expected to occupy the chair and preside over any rule change action.

Political scientist Norm Ornstein, in a recent op-ed in the Washington Post titled "Five myths about the filibuster," reminded that the Senate wasn't built on supermajority requirements and that the filibuster didn't even exist when the body was founded.

"Democrats have proposed, for example, requiring that senators actually speak on the floor, or flipping the standard such that the Senate would require 41 votes to continue debate rather than 60 to end it," Ormstein writes. "These reforms to the filibuster would not weaken the Senate, but would restore it to its rightful place in our political system."

What did the founders say?

Many defend the filibuster by arguing the founders supported the idea of a supermajority as evident by the checks and balances in American democracy.

However, Congressional Research Service scholar Walter J. Oleszek argues, "Overall, the Framers generally favored decision-making by simple majority vote. This view is buttressed by the grant of a vote to the Vice President (Article I, section 3) in those cases where the Senators are 'equally divided,'" he said.

Additionally, Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers that allowing minorities to overrule the majority would make for "tedious delays; continual negotiation and intrigue; contemptible compromises of the public good."

What do Democrats say?

Biden said last month in an exclusive interview with ABC News "World News Tonight" Anchor David Muir that he would support changing Senate rules to allow voting rights legislation to proceed -- but only if necessary.

Asked by Muir if he supported an exception, or carveout to the filibuster -- the long-standing Senate procedure that requires 60 senators to vote to allow a bill to move forward -- Biden said he did -- as a last resort.

"I don't think we may have to go that far," the president said, "but I would be if that's, if it's -- the only thing standing between getting voting rights legislation passed and not getting passed is the filibuster, I support making the exception of voting rights for the filibuster."

Schumer has vowed that a vote on changing the Senate rules is coming if Republicans continue to block voting rights legislation. In a letter to colleagues on Monday, he wrote that he intends to force a vote on changing the rule on or before Jan. 17, Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

The minority leader reaffirmed on Monday night that if Republicans, again, block Democrats' attempt to hold a vote on an election reform bill, as is expected, Schumer will open debate on the filibuster and possible rules changes.

"If Republicans refused to join us in a bipartisan spirit, if they would continue to hijack the rules of the Senate to turn this chamber into a deep freezer, we're going to consider the appropriate steps necessary to restore the Senate," Schumer said, despite not appearing to have the votes to change the rules.

What are Republicans saying?

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell preemptively warned of a "scorched earth" last year when Democrats won their majority to threaten against ending the filibuster -- a stance he had firmly stood behind, despite using the nuclear option for Supreme Court nominees.

Ahead of Democrats pushing voting reforms this week, McConnell accused Senate Democratic leaders of trying to "bully" their members into changing the Senate rules if their voting rights bills aren't approved.

"The Senate Democratic leaders are trying to use a 'big lie' to bully and berate their own members into breaking their word, breaking the rules and breaking the Senate," McConnell said in a floor speech Monday. "Every hysterical claim that our democracy is in crisis rings hollow."

"Breaking the Senate itself and nuking the filibuster would cause a massive political power outage for many millions of American citizens of entire states," McConnell added.

He warned that any changes to the filibuster would not only change the Senate -- but American lives.

"For decades, both senators and citizens have been able to take for granted that everybody gets a voice even when they don't have a divided government. If this unique feature of the Senate is blown up, millions and millions of Americans voices will cease to be heard in this chamber," McConnell said. "It would destroy a key feature of American government forever. And senators on both sides know it."

Pressure builds on Democrats Manchin, Sinema

While moderate Democrats Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona say they support voting rights reforms, they have echoed McConnell's arguments that the filibuster is designed to protect the minority and that it's dangerous for Democrats to carve out an exception.

"If we eliminate the Senate's 60-vote threshold, we will lose much more than we gain," Sinema wrote in a Washington Post op-ed last year.

"The filibuster is a critical tool to protecting that input and our democratic form of government. That is why I have said it before and will say it again to remove any shred of doubt: There is no circumstance in which I will vote to eliminate or weaken the filibuster," Manchin wrote in an op-ed of his own.

Manchin has maintained that any rules changes must be done with bipartisan support.

But powerful House Democrats like Rep. Jim Clyburn, D-S.C., are turning up the pressure on those senators and breaking down those arguments.

"I am, as you know, a Black person, descended of people who were given the vote by the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution. The 15th Amendment was not a bipartisan vote. It was a single-party vote that gave Black people the right to vote," Clyburn said on "Fox News Sunday."

"Manchin and others need to stop saying that because that gives me great pain for somebody to imply that the 15th Amendment of the United States Constitution is not legitimate because it did not have bipartisan buy-in," he added.

The West Virginia senator on Tuesday told reporters, "We need some good rule changes to make the place work better, but ending the filibuster doesn't make the place work better."

But last week, Manchin appeared to move slightly off his hardline stance, refusing to rule out a Democratic-only solution on voting rights if Republicans refused to negotiate.

He called passing a change to the Senate rules a "heavy lift" during a gaggle with reporters and emphasized that his "preference" would be Republican buy-in, but stopped short of calling Republican support a "red line."

One more thing

According to the U.S. Senate website, the word "filibuster' is derived from a Dutch word for "freebooter" and the Spanish "filibusteros" -- used to describe pirates.

ABC News' Trish Turner and Allison Pecorin contributed to this report.