Screen time and kids: New findings parents need to know

The digital age has made screens more accessible and portable than ever. Although the full implications of screen time exposure on young kids whose brains are still developing is not yet known, there is concern that screen use can affect cognitive and language development, lead to problems in school and make some mental health disorders worse.

Because of these concerns, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) created guidelines in 2016 for parents to limit children's screen time.

Some of those guidelines include:

- Avoid screen time for children younger than 18 months, with the exception of video chatting.

- From 18 to 24 months, introduce digital media by watching quality programming like PBS Kids or Sesame Workshop with children.

- For ages 2 to 5, limit screen time to 1 hour per day and watch quality programming with kids.

- For ages 6 and up, limit media use and device type, and ensure media use does not interfere with sleep and physical activity

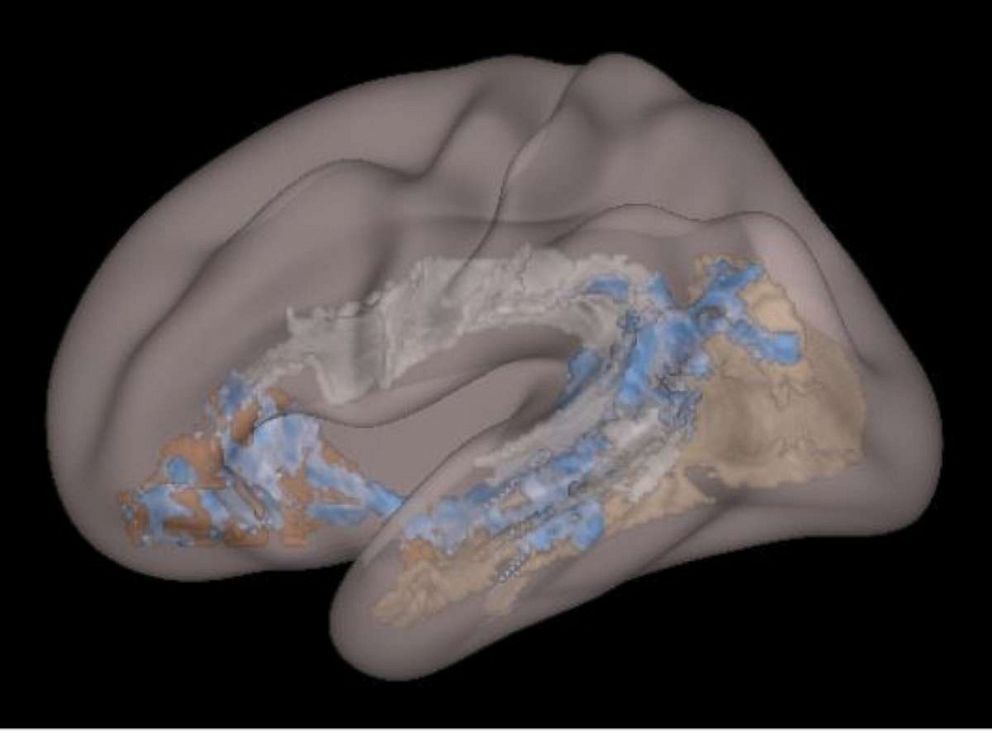

A new study from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center published in JAMA Pediatrics showed concerning evidence that brain structure may be altered in kids with more screen use. Researchers looked at brain MRIs in 47 preschoolers and found that screen time over the AAP's recommendations was associated with differences in brain structure in areas related to language and literacy development.

Importantly, cognitive testing was not different among children with more or less screen time when correcting for household income. But the findings provide some evidence that support caution with screen time during this crucial developmental stage.

According to David Anderson, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist and senior director of National Programs and Outreach at the Child Mind Institute, it’s especially important “to be very cautious when using screens with young kids, as this study highlights, as young kids are in a critical developmental period."

At this stage, children "require face-to-face interaction," said Anderson to reach developmental milestones including building language and social skills. During this time they also develop empathy, the ability to understand emotion, and "build stamina to navigate personal situations," he said.

This study brings up the important question: What is screen time replacing? It is unclear if the findings are related to the screen time itself, or from the lack of other activities that screen time replaces, such as reading with parents, socializing and outdoor play.

Is all screen time bad? Some forms may be worse than others. According to another recent study in JAMA Pediatrics that analyzed prior research on screen time in kids from ages 4 to 18, TV and video games in particular, were associated with worse academic performance, especially in teens.

On the other hand, Anderson pointed out that "there can be positive effects" of screen time including "increasing social connection, particularly in kids in marginalized groups, where finding online communities where they can be accepted and supported can be immensely positive."

And in teenagers and adults, "small doses of screen time can be a mental health-positive way of relaxing, reducing stress, and connecting socially to friends and family members."

What can parents do? In addition to the recommendations by the AAP to restrict screen time in young children, as children get older it is important to place limits not just on how much screen time, but when to allow screen time. Screen time later at night can interfere with sleep, so the AAP recommends parents pay special attention to limiting nighttime device usage.

It’s important to make an effort to spend time and socialize together, and promote activities like playing outdoors or participating in athletics.

"If your teenager is generally actively participating, getting homework done, having face-to-face interaction with family members and friends, and has extracurricular and physical activity … parents can relax a little [about screen time] … and reduce the guilt," Anderson advised.

Angela J. Ryan, M.D., is a cardiology fellow at the George Washington University Hospital working with the ABC News Medical Unit.