The science behind Major League Baseball's latest sticky situation

This is an Inside Science story.

On June 15, Major League Baseball announced its plan to more aggressively enforce often-ignored rules prohibiting the use of foreign substances by pitchers. The league is now encouraging umpires to check pitchers frequently during games, especially for the presence of anything sticky on the players' hands or uniforms that might be used to help grip the ball. The league will eject and suspend players who violate those rules.

Across Major League Baseball this season, hitting performance has been plummeting, and the new emphasis on enforcing the rules, which went into effect June 21, likely will reduce the rate at which pitchers are able to spin the ball. This in turn should make the ball less likely to dart and dive as violently, making it easier to hit.

The spin rate of pitches has indeed dropped considerably since the first announcements about enforcing the rules. But changing this one aspect of the game may have far reaching consequences that could include a possible increase in injury risk.

More grip, more problems

Some pitchers mix sunscreen with the rosin that's found on every Major League mound to increase the friction between their fingers and the ball. This helps them control the ball, which can actually be quite slippery. Mike Sonne, the chief scientist at the company 3MotionAI and a baseball biomechanics researcher, referred to using those substances as the equivalent of driving 60 mph in a 55-mph zone. "It is technically breaking the rules, but it's not an egregious breaking of the law," he said.

Other substances, including glues, custom mixes and an adhesive called Spider Tack, are so sticky they enable pitchers to spin the ball at astonishingly fast rates. It can make hitting a baseball, often dubbed the most difficult thing to do in sports, almost impossible. That's why Sports Illustrated recently called the use of sticky stuff one of the biggest scandals in sports.

"Spider Tack is the equivalent of going 90 mph," said Sonne.

However, a sudden change to remove all substances -- everything from the simple sunscreen mixture to Spider Tack -- in the midst of a season can be disruptive. Adapting to a new grip while trying to deliver the same quality of pitches could force pitchers to change the way they use their muscles as they throw the ball.

"To throw a baseball 95 miles an hour -- it's the height of modern athletic achievement," said Peter Chalmers, a researcher and orthopedic surgeon at the University of Utah. He also works with the Salt Lake City Bees minor league baseball team. "To make a huge, immediate, let's-change-this-right-now thing that affects the pitcher's motion, I think is somewhat problematic."

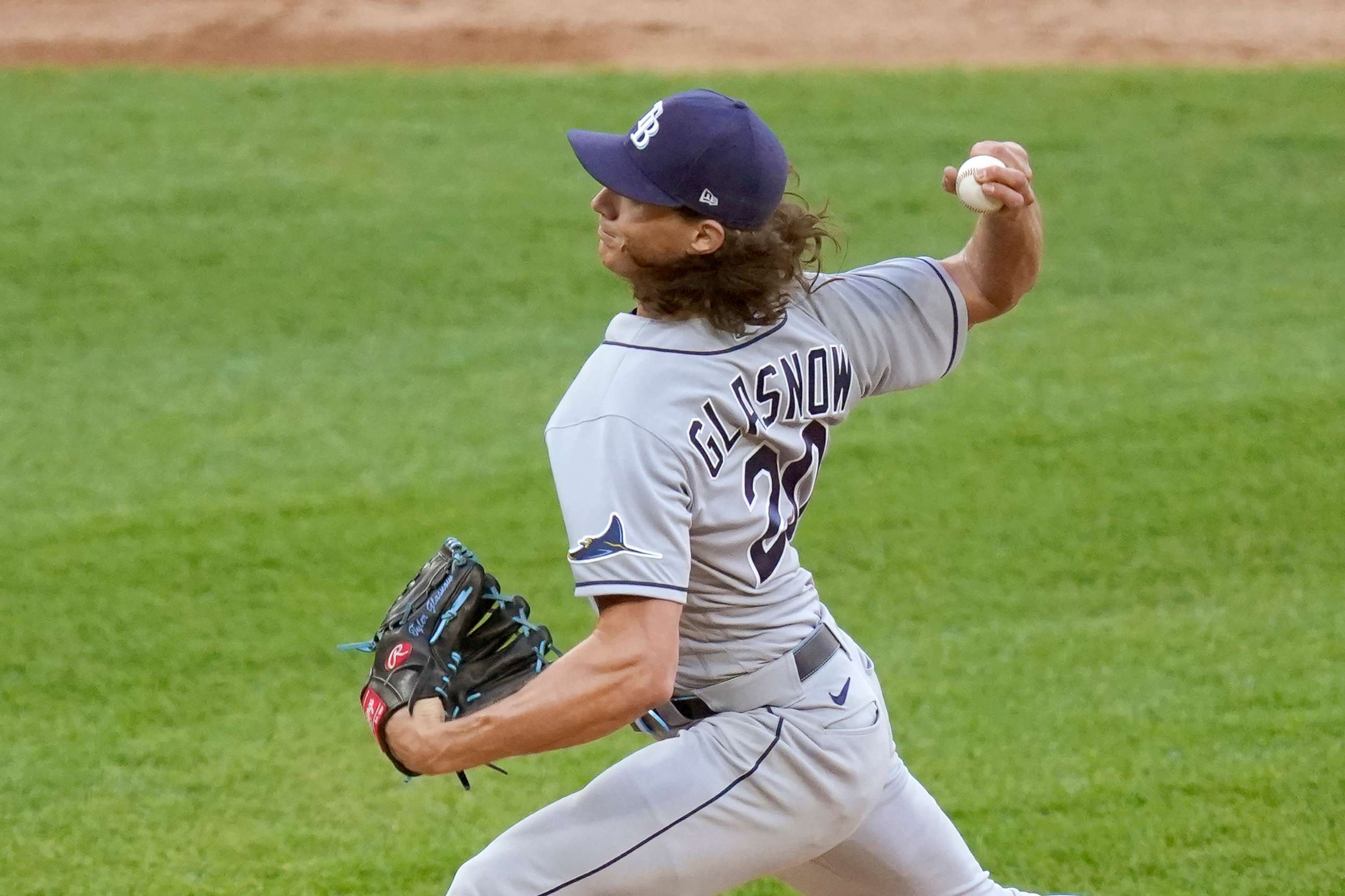

At least one player is arguing that the change is indeed problematic. Last week, Tampa Bay Rays pitcher Tyler Glasnow said in a press conference that he stopped using sunscreen to enhance his grip for two starts this June. After the first one, his arm muscles were unusually sore. During his second outing, he suffered an injury to the ulnar collateral ligament in the elbow. He said he believed the change led to his injury.

Though Chalmers doesn't think previous research has shown convincing evidence that eliminating sticky stuff will cause injuries, other researchers think the change could increase the risk of arm and elbow injuries. The reason why is a reduction in friction.

Intuition and injury risk

A pitcher's fingers are adapted to producing a certain amount of force, said James Buffi, co-founder of the biomechanics company Reboot Motion, who has also worked as an analyst with the Los Angeles Dodgers. "When you take away the sticky stuff, now you all of a sudden you need more finger force to get the same resulting friction."

If a pitcher ramps up that finger force it can cause him to use the muscles in the arm differently and tire them out faster.

"Pitchers who report pitching while fatigued are six to 30 times more likely to have an elbow injury," said Sonne. "We might end up seeing another spike in elbow injuries."

There's a relatively high risk of injury in pitchers in any season, since pitchers throw the ball so hard, over and over, at the limits of what human anatomy can accomplish. If the muscles in the forearm get tired, the worry is, they may be less able to protect the elbow.

While this relationship seems intuitive, it's not clearly established by evidence, said Chalmers. Past research, he said, has not shown a clear tie between pitching with higher spin and injury risk. "I think like many ideas that make intuitive sense, it doesn't necessarily mean that it translates directly into what we see clinically," he said.

But, he said, the true risk will only become clear in the coming weeks and months. That will require data about how much pitchers pitch and their injuries. The analysis could be complicated by last year's pandemic-shortened season.

Pitching without sticky fingers

Buffi said that in the near future, teams should put extra emphasis on monitoring the fatigue and soreness of their pitchers because it usually takes muscle a couple of weeks to adapt to new levels of stress.

It's possible that the change may even lead pitchers to lose their finely tuned control over where the ball goes, resulting in more walks and more batters getting hit by the ball, which could make games move more slowly and be less enjoyable -- the opposite of MLB’s intentions with its rule change.

But the flip side is that having unenforced rules about how pitchers operate is how the game arrived at this issue.

"I mean, if it's the rule," Chalmers said, "then I do think it makes sense for everyone to play by the rules."

Inside Science is an editorially independent nonprofit print, electronic and video journalism news service owned and operated by the American Institute of Physics.