‘We’re being scapegoated’: Asians and Asian Americans speak out against spate of violence

Monthanus Ratanapakdee will always remember her father as a gentle soul.

Vicha Ratanapakdee had moved to San Francisco from Thailand four years ago to help his daughter and son-in-law, Eric Lawson, take care of their two sons. During that time, he came to be known as “grandpa” throughout his neighborhood, where he’d made it a ritual to go on morning walks each day.

On Jan. 28, the 84-year-old was on one of those walks when a man rushed him and forcefully knocked him to the ground, surveillance video shows. Vicha Ratanapakdee went to the hospital, where he died two days later.

“He never wake up again. He [was] bleeding on his brain,” Monthanus Ratanapakdee told “Nightline.” “I called him, ‘Dad, wake up.’ I want him to stay alive and wake up and come and see me again, but he never wake up.”

The incident that led to Vicha Ratanapakdee’s death is only one of several assaults in Northern California over the past two months -- some against elderly Asian Americans -- and comes on the heels of nearly a year of growing anti-Asian hate amid the pandemic.

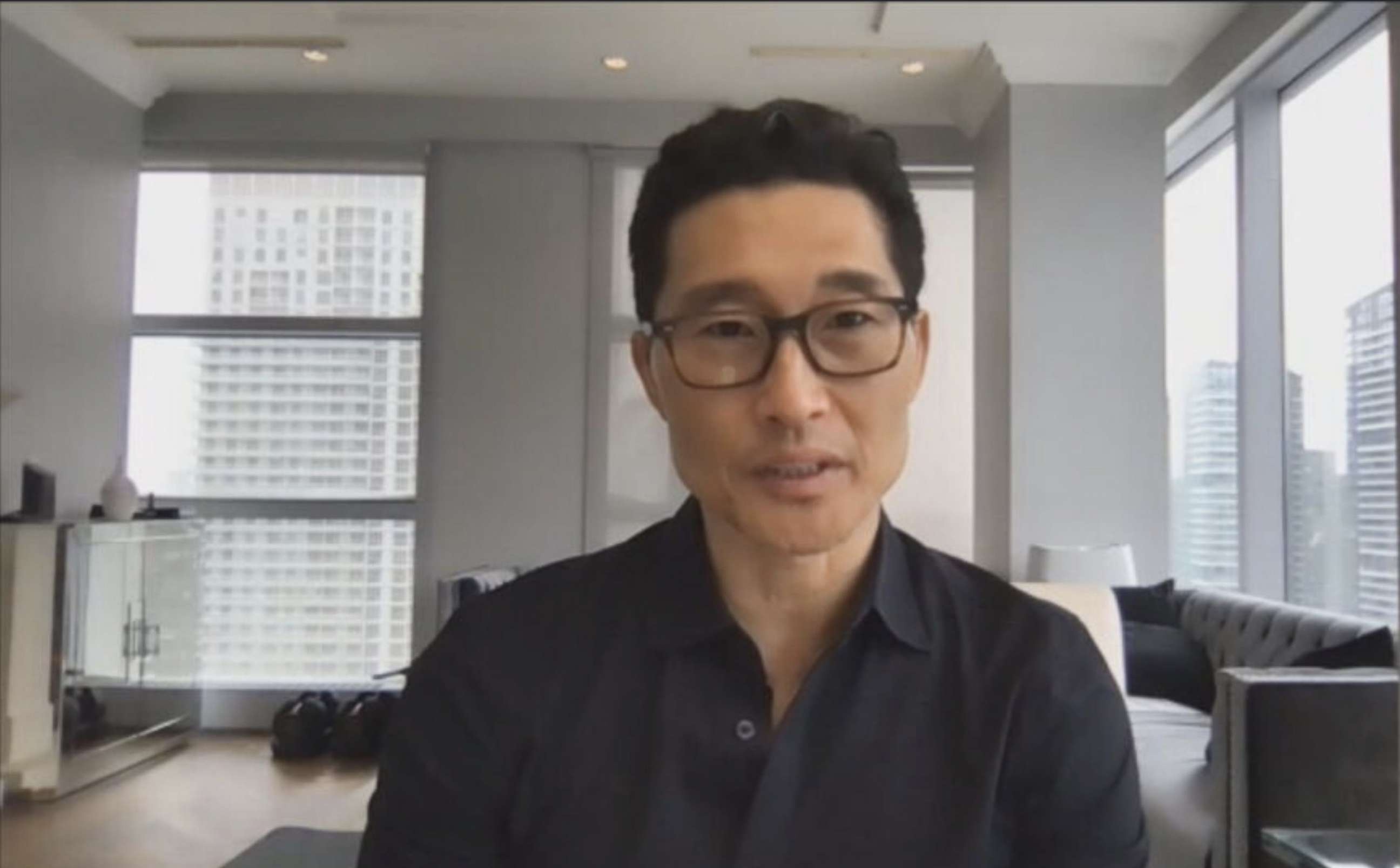

The recent attacks have drawn the attention of actors Daniel Dae Kim and Daniel Wu, who’ve spoken out against the violence and offered a reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of those involved in the attack of a 91-year-old man in Oakland’s Chinatown.

“It was a very visceral response. I got very angry because I thought, ‘This is now a year of these kinds of things going on,” Kim told “Nightline.” They’re attacking our most vulnerable population, and no one in the mainstream media outside of the Asian American echo chamber is picking up this story.”

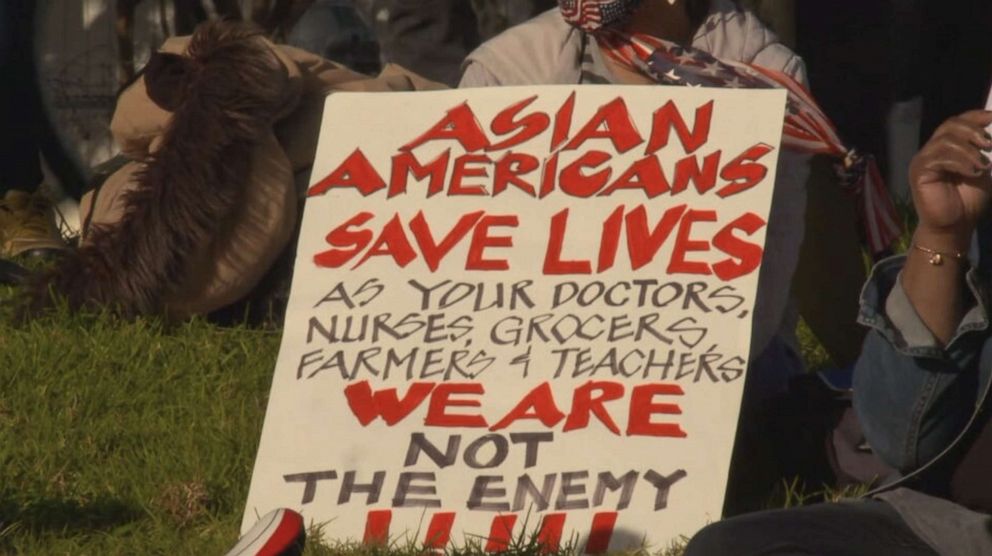

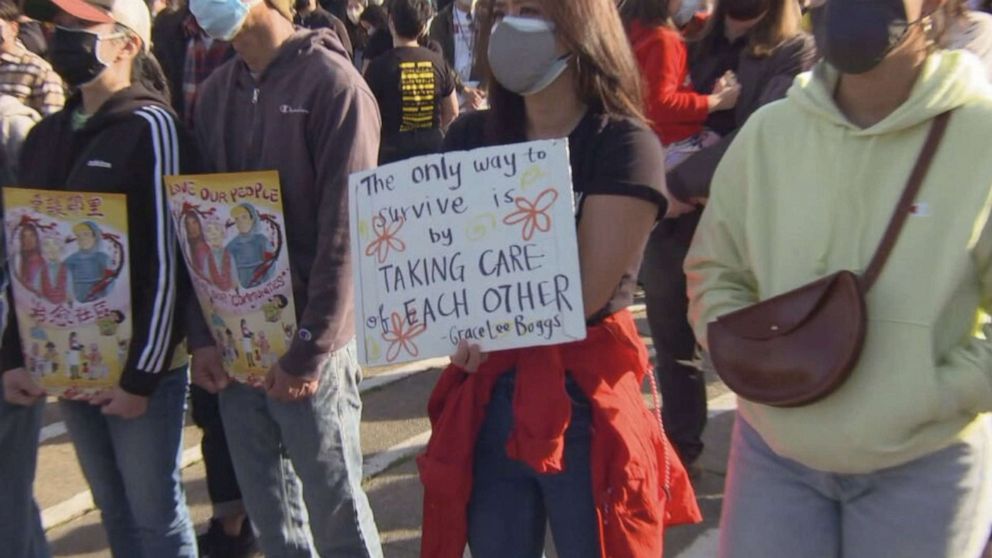

Public outrage over the incident grew as videos showing the violence were shared on social media. More than 1,000 people took to the streets to speak out against the anti-Asian violence and call for racial justice.

A 19-year-old suspect who was arrested in connection to Vicha Ratanapakdee’s death is now charged with murder and elder abuse. He has pleaded not guilty.

The suspect's lawyer has said his client had “no knowledge of Mr. Ratanapakdee’s race … since his face was fully covered” with a mask and hat. The lawyer also insisted the attack wasn’t racially motivated, but rather, it was due to “a break in the mental health of a teenager.”

While some of the suspects in the latest attacks have been Black, Kim says it’s “not just a Black and Asian issue. It is something in the psyche of this country where somehow it’s OK to abuse physically or verbally abuse Asian Americans.”

“We’re being scapegoated,” the actor added.

Community leader and Oakland native Connie Wun, Ph.D., agrees. She says that the number of anti-Asian incidents grew dramatically with the pandemic, citing former President Donald Trump’s rhetoric in part as a catalyst.

“When the previous administration said things publicly, like ‘the Wuhan virus’ or ‘this is the China flu,’ unapologetically, he helped to stoke the fires of anti-Asian violence against our communities,” she told “Nightline.”

Between March and December last year, the organization Stop Asian American and Pacific Islander Hate, which launched in response to the growing sentiment, recorded nearly 3,000 reports of anti-Asian hate incidents nationwide. The New York City Police Department also reported a 1,900% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes last year.

Wun says these reports barely scratch the surface of the real numbers.

“We tend to not want to talk about the violence that’s happening in our communities,” Wun said. “We don’t want to cause more trouble sometimes. We also know that some of our community members are undocumented. That leaves us also susceptible to deportations. We don’t want to cause kind of more attention to our communities.”

She went on, “I think a lot of our elders have tried to acclimate and acculturate into this country and have faced some backlash if they dare to kind of speak.”

Historically, Wun noted, there have been conflicts between Blacks and Asians in larger cities. The Los Angeles riots, perhaps, being the most dramatic of them all.

“White America tends to privilege Asians and Asian Americans in ways that they do not our Black and Latinx community members,” Wun said, referring to the “model minority myth.”

She said the myth suggests Asian Americans are “excelling,” and pointed to portrayals of their lives in films and TV shows like “Crazy Rich Asians” and “Bling Empire.”

“Those are not the real stories. Those are not the real-life depictions of what our communities really look like,” she said, adding that many are living in poverty and that their stories aren’t being highlighted.

Following the death of George Floyd in May last year and the subsequent outcry for Black lives, Kim believes both communities’ fight for racial justice is more unified than ever before.

“Historically, there have been tensions between the African American and Asian American communities, but I really do think George Floyd galvanized the two communities in a way that I’d never seen before,” Kim said. “I’ve never seen more Asian Americans standing in support of Black Lives Matter and marching all over the country, myself included. Everyone was able to recognize the injustice in the system, and so, I’m hoping that momentum carries over into these cases because it really ultimately is about a collective unified response to injustice.”

Wun said that while elderly Asian Americans might be hesitant to speak out on the injustices they’re facing, the younger generation has been more forthcoming to defend their elders.

Will Lex Ham is one member of that younger generation. The actor's turn toward activism began with demands for more Asian American representation in the mainstream and soon grew to be much more.

At the height of the pandemic, Ham organized several protests demanding an end to the xenophobia and rise of anti-Asian sentiment. He eventually joined forces with Black activists in solidarity marches across the city, chanting, “Asians for Black Lives Matter.”

On Feb. 10, Ham flew from New York City to the Bay Area to join locals who walking around the streets offering assistance to elders and business owners in an effort to ensure their safety.

“We’re sick and tired of being invisible and ignored in our country,” Ham told “Nightline.” “The pain of the Asian community has been muted for decades.”

Ham spent his first weekend in the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown, handing out self-defense whistles and pamphlets in Chinese with information on how to report hate crimes in their communities. Since arriving in the Bay Area, he’s also met with local leaders. Though he was experienced in Ham said the solidarity work happening in the Bay Area inspired him.

“Asian American history is American history that needs to be taught,” Ham said. “And so, when I came to the Bay Area, I first learned about all these incredible Asian Americans who’ve been doing the work for decades. … They’re doing incredible work that needs to be seen and shown throughout the rest of the country. They’re working, building, utilizing their relationships with Black community leaders and a lot of solidarity work that has been happening here to condemn the violence.”

For Ham, following the lead of long-time local community leaders was important for several reasons.

“These local organizations that don't get a lot of light, they don't get a lot of shine because a lot of volunteer work is not sexy, you know. It's not attractive. But they're doing incredible work that needs to be seen and shown throughout the rest of the country,” he said.

The goal, he says, is not just to highlight their work but to also educate and raise awareness among his followers nationwide, including himself.

“I found it incredibly refreshing that the Bay Area activists who've done this work for so long, instead of calling us out, they called us in. And they wanted to share their wisdom and their methods of action and maybe they don't agree with everything that we do, but they see the power that we have in mobilizing the people.”

However, the efforts to condemn anti-Asian hate -- and resistance to that -- reach even to the level of the government.

Last March, New York Rep. Grace Meng introduced a resolution to condemn anti-Asian rhetoric. While the resolution passed in the House, 164 Republicans had voted against it.

For Meng, the response to her resolution was even more upsetting. She said she received voicemails in which people mentioned the “karate kid virus” and “Chinese virus,” and called her names.

“There was just so much hate,” she said. “And even though I and so many Asian Americans were born and raised in the United States of America, there are always instances where we are made to feel that we are foreigners, that we are just not good enough in some people’s eyes to be American.”

“Our people are getting attacked. Our people are getting harassed, spat on, beat up, slashed,” she added as she began to tear up. “Please, somebody pay attention. Please, notice us. Give me confirmation that I am American, too. I just haven’t been able to feel that in a long time.”

Like countless Black families around the country are fearful for her childrens’ lives, Meng said the recent spate of attacks prompted her to sit down and have a serious conversation with her kids about race and their safety. Until now, she said, these conversations had only been superficial by comparison.

“My kids are in elementary school and middle school. I never had substantive, in-depth conversations about racial slurs,” she said. “But when this started happening, I did have one of our first real sit-down conversations. I said … ‘There are people in this country who will take a look at you and without knowing anything about you, may call you something that is derogatory, may even try to cause harm to you. And I just told them that this is what some people think -- do not be hurt by it -- and to let an adult know in case I’m not around.”

Even before losing her father, Monthanus Ratanapakdee said these issues were something she and her kids faced firsthand. She mentioned an incident where she was outside with her kids when someone yelled derogatory terms at her.

“My kids [says], ‘Mom, they are yelling at us,’” she said. “And then we just stay away… We know there is violence so we just walk away.”

Still, the pain of that reality cannot be matched by that of losing her father. As the media continues to report on these incidents, Ratanapakdee has to relive the incident each time she sees the video of her father being pushed to the ground being played on TV.

“It’s painful,” she said, crying. “I don’t want to see it. It’s a broken heart.”

However, Lawson, her husband, said they know that they’ve got to “fight back.”

“We know that we’ve got to speak up and we can’t be quiet about this,” he said, “because that’s why this keeps happening.”