How Richmond is addressing the debate over Confederate monuments 1 year after Charlottesville

RICHMOND, Virginia. -- On Richmond’s distinguished Monument Avenue, a statue of Robert E. Lee and his horse stand triumphant, just one of the many Civil War monuments erected in what was once the capital of the Confederacy.

Monument Avenue as a whole was designed to “capture in monumental ways a single narrative of the Civil War -- that narrative based on the ideas embodied in Lost Cause-thinking and the Jim Crow South," said Bill Martin, the director of Richmond’s historic Valentine Museum.

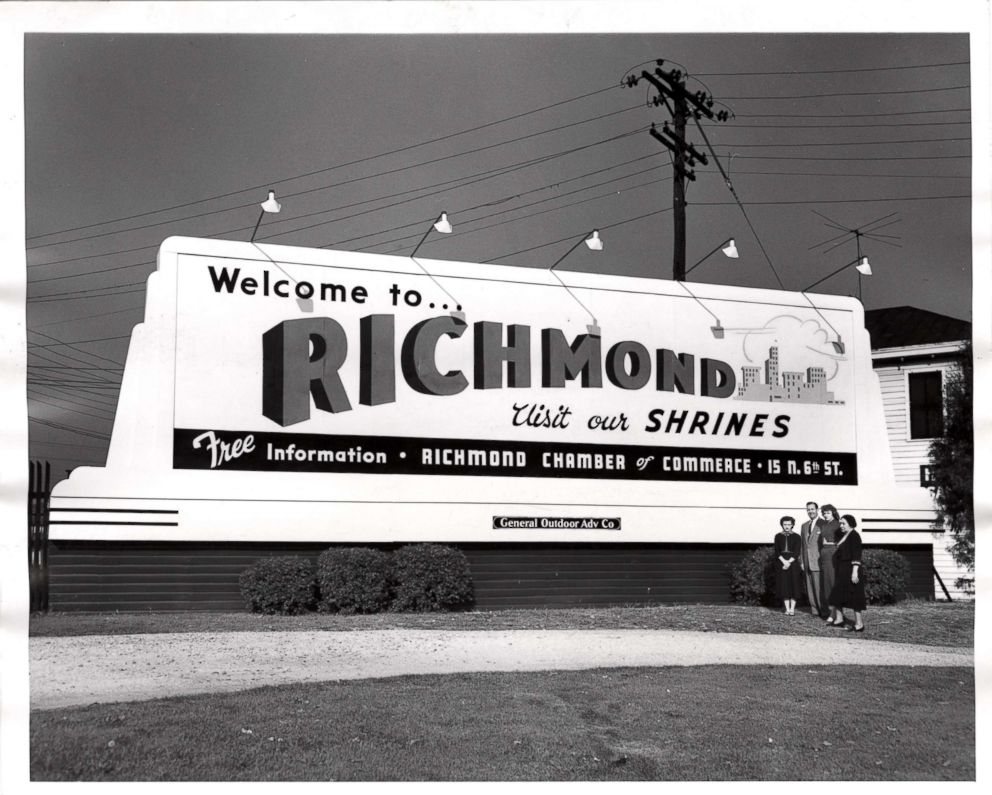

For many years, Martin said, “there was this notion that we could become a tourist destination” because of the statues of Confederate heroes, including Lee, who led the Confederate army, and Jefferson Davis, who was the president of the Confederacy. Decades ago, there were even nearby billboards that promoted Richmond’s “shrines.”

But activists who are pushing to have the Confederate statues removed fear what kind of tourists such statues could attract-- and what kind of message they send today. The “Lost Cause,” for example, is a narrative that downplays or omits the role of slavery in the Civil War, painting it instead as a heroic struggle by an outnumbered army to preserve the Southern way of life.

The fear of what kind of visitors the monuments could draw became more pronounced in the wake of the violence in nearby Charlottesville last year, where a rally of white supremacists turned deadly.

“These monuments, they'll continue to be these pilgrimage sites and as long as they're up, you’re going to see more Charlottesvilles,” said Austin Gonzalez, a Richmond resident and political activist. “Hopefully not as tragic, but if we allow these rallies to happen and these monuments to stay up, it's inevitable. It's inevitable that events like this will continue to happen.”

Looking back at Charlottesville

On Friday, Aug. 11, 2017, white supremacists descended on Charlottesville for the next day’s “Unite the Right” rally, the stated purpose of which was to protest the city’s planned removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. But the protests quickly became a show of force for white supremacists, many of whom marched with neo-Nazi flags and tiki torches while chanting racial and ethnic slurs.

Gonzalez said felt compelled to make the roughly hour-long drive from Richmond to Charlottesville to protest against the alt-right groups that had gathered there last August. Many of the right-wing protesters came armed, and the tension between the two groups continued to escalate throughout Saturday morning. Two state troopers who were part of the response to the events in Charlottesville died when their helicopter crashed several miles outside the city.

“The entire day felt like a battlefield,” Gonzalez said.

The violence escalated Saturday afternoon when a 20-year-old Ohio man, James Alex Fields, allegedly accelerated his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer and leaving 19 others injured, five critically.

Gonzalez said that he was “not far away” from the site of the crash.

“I thought somebody was shooting into the crowd,” Gonzalez said of the commotion.

Gonzalez’s friend Nick Da Silva also traveled from Richmond to Charlottesville last year and was closer to the car at the time of the crash.

“I remember seeing a lot of people injured, seeing her body fly after the car came through,” Da Silva said.

DaSilva said that for months after the rally, the sound of screeching tires brought him back to that moment, as did the sight of any cars similar to the model driven by Fields. Fields has pleaded not guilty to federal hate crime charges and has also been charged under Virginia law with murder and other crimes. Fields is currently in jail awaiting trial.

For his part, President Donald Trump, when pushed to address the white supremacist violence in the days after Charlottesville last year, said there were “very fine people on both sides” of the protests. And on Aug. 17, 2017, five days after the deadly protest, Trump weighed in on the monument debate as well, posting a string of tweets where he bemoaned the “removal of our beautiful statues and monuments.”

Now, nearly a year later, the confusion and indecision around the statues remain.

How other cities have dealt with Confederate statues

In Charlottesville, the Lee statue still stands, although it was covered for several months by a “mourning shroud” in light of the deaths of Heyer and the two state troopers. The shrouds were removed in February and the statue continues to be entangled in an ongoing legal battle.

In other cities, local officials acted quickly to remove their statues. In Baltimore, the statues were removed overnight in August 2017 after the violence in Charlottesville. New Orleans had already removed several of its Confederate monuments -- including one of Lee -- earlier in 2017.

But across the South, the statues remain. One city that has been notably public and purposeful in their decision-making around their removal is Richmond.

In June 2017, two months before the Charlottesville protests, Richmond officials were grappling with what to do. They established a Monument Avenue Commission and held a public forum in August 2017 that more than 500 people attended and in which “organizers struggled to keep the dialogue civil,” the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported.

After Charlottesville, the forums were still held but in smaller settings, eventually leading to the publication of a report in July of this year. The commission’s report suggested adding signage near the statues of specific Confederate leaders -- including the large one of Lee on Monument Avenue -- “that reflect the historic, biographical, artistic, and changing meaning over time for each.” The Lee statue has been the site of several protests in the past year.

The commission also said that it would support or initiate the removal of the statue of Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy, from Monument Avenue, citing the fact that he was not a Virginian himself and noting that “of all the statues, this one is the most unabashedly Lost Cause in its design and sentiment,” referencing the ideology that paints the Confederates as heroic.

Some of the other recommendations from the commission included employing local artists to create new works that will “bring new and expanded meaning to Monument Avenue,” the creation of an exhibit at a local museum that examines the statues and their subjects, and creating an app to explain the new signage.

A wide range of opinions

The commission’s recommendations have yet to be implemented, but Richmond residents have a wide array of opinions about the fate of the statues, which they shared with ABC News in early July. Many of the opinions fell along racial and generational lines.

Harrison Taylor, a leader of a local chapter of the Sons of the Confederacy, believes that the statues “honor the valor and the sacrifice of the men” that served under the Confederate leaders, including his own family members.

“They were put up in period time where people knew first-hand the sacrifice of the soldiers and their cause and so no one really has the authority to do anything different,” Taylor, 67, who is white, said.

Jamele Pope, who is black and was born and raised in Virginia, said that she has experienced “racism and segregation” and has seen members of the Ku Klux Klan marching in the past. In spite of that, she doesn’t feel that the statues need to be removed.

Instead, Pope, who has worked as a teacher, said that the statues should stay in place and city funds should be focused on “fixing what needs fixing” like infrastructure and public education.

“We should grow from the mistakes of the past,” Pope said.

Her friend, Marva Maynard, an aspiring artist who is black, supported the idea of adding more statues to the landscape in Richmond.

“If you’re trying to depict history, show the whole picture,” Maynard said.

Robert Rosch, a 36-year-old white Uber driver, described himself as “indifferent” to the debate, both saying that it would be good to see some more statues added and some of the older ones removed, but overall feeling that “it’s better to use [the money] elsewhere.”

Michael Couchman, who lives near Monument Avenue and is white, said he doesn’t believe the statues should be destroyed but isn’t opposed to seeing them moved. Overall, he said that the issue doesn’t impact him a great deal, but “it does for other people and because of that, it's still important.”

Some, including a white teacher who recently moved to Richmond but asked that her name not be used because of the concerns of her employer, defended the statues and their meaning. She said that Lee “was actually a good man … who fought for what he believed in.” She said that she didn’t view the monument “as a racial totem.”

But others very clearly do, said Aneesha Rao, who recently moved to Richmond from northern Virginia.

“Any relic that upholds a reverence to a period of time that is marked by slavery for so many people is frightening,” said Rao, 28. “Public spaces have to be defined by security.”

Jesse Harris, 59, was born and raised in Richmond and is black. He works at a food cart a block away from the White House of the Confederacy, Davis’ home during his time in power. The house has now been turned into a museum.

“They can move it or don’t move it,” Harris said, noting his indifference to the debate over what to do with the statue of Lee.

“It’s a part of history just like the revolutionary war,” Harris added. “If you take away from history, the young people of today will be ignorant of the history -- good or bad.”