In return to Justice Department, Garland brings background in domestic terror to a nation in crisis

On the morning of the deadliest domestic-based terror attack in U.S. history, Merrick Garland was seated in his office on the fourth floor of the Justice Department in Washington. As he read through emails and bulletins from U.S. attorney's offices around the country, an alert popped up on his computer terminal.

It said, "Urgent report."

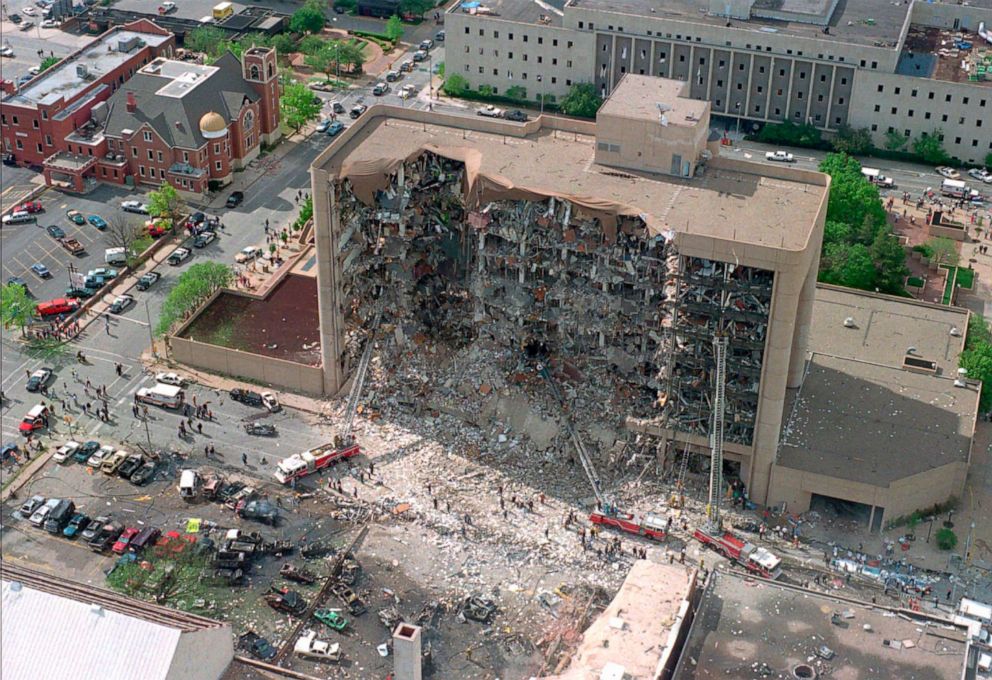

Garland, whose confirmation hearing for U.S. attorney general gets underway on Monday, clicked on the prompt. The alert was an unspecific bulletin from the acting U.S. attorney in Oklahoma advising that there had been an explosion at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City, and that the office would be sending officials to investigate.

Garland turned on his TV to CNN as updated bulletins began to come in, each with increasingly dire language describing the bombing.

It was only after the third "urgent report" arrived that TV cameras started to show the shocking effects of the 1995 attack, which a horrified nation would soon learn took the lives of 168 people and injured scores more.

"We didn't have internet access in the Justice Department in those days, so the method of finding out what was happening elsewhere in the country was CNN," Garland said in a 2013 oral history interview recorded by the Oklahoma City National Memorial and obtained recently by ABC News.

For Garland and other DOJ prosecutors who had started to file into his office, the images were reminiscent of the 1983 terrorist attack on the Marine barracks in Lebanon.

Over the next several hours, Garland, who at the time was serving as principal associate deputy attorney general, dispatched officials from the department's Criminal Division as investigators began to comb through the massive crime scene for clues. Meanwhile, the bombing had left the nation on edge and fearful of further attacks, as bomb threats were phoned in against courthouses and other federal buildings.

Garland asked then-Attorney General Janet Reno to send him to Oklahoma City, where he would go on to take a leading role in overseeing the investigation into the attack and the government's effort to bring domestic terrorists Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols to justice.

Garland's longtime friend Jamie Gorelick, who as deputy attorney general was Garland's immediate superior at the Justice Department, said it was a massive undertaking.

"He made sure that every single decision that was made by the FBI and by the prosecutors was in accordance with the law and absolutely bulletproof in the prosecution itself," Gorelick said in a recent interview with ABC News. "He was masterful in working with both jurisdictions and people who had different interests, and bringing them to the table really by the force of what was right. You know, many other people you could imagine in that situation would have provoked fights, and he did the opposite."

Garland, who later played a key role in prosecuting domestic terror cases involving Unabomber Ted Kaczynski and the bombing at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, would go on to say in 2013 that the Oklahoma City investigation was the most significant and important case he had ever worked on.

"Obviously this is the central thing, most significant thing I worked on," Garland said. "It was the thing that I feel like I made the biggest -- I was able to make the biggest personal contribution to something."

But with his return to the DOJ as attorney general pending Senate approval, former officials and terrorism experts say Garland faces a far more daunting and urgent domestic terror crisis than at any point in modern American history.

A domestic terror flashpoint

The Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol, coming one day before President Joe Biden's formal announcement of Garland's nomination, served as a flashpoint in the crisis -- and has prompted an investigation of unprecedented scale as the Justice Department works to prosecute potentially hundreds of supporters of former President Donald Trump, some of whom could face years in prison on charges of sedition and attacking law enforcement.

And while Garland will bring substantial experience and familiarity with domestic terror cases, experts say the landscape that he and department leadership will have to confront is not only vast in scope but rapidly evolving after four years of Trump repeatedly seeking to downplay the threat posed by far-right and racially motivated extremists.

"We've had domestic terrorism cases and problems in this country for a long time," former deputy attorney general James Cole said. "But it's never had the kind of permission that it has right now to operate out in the open and to operate without any sort of restraints. And I think that's going to be one of the big challenges. You've taken the lid off and brought it out into the light of day a lot more."

Javed Ali, a former senior director for counterterrorism in the National Security Council who served during the first year of the Trump administration, said signs of a rising threat from far-right extremists began to appear early in Trump's tenure, and culminated with the August 2017 "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville where a neo-Nazi plowed his car into a crowd of protesters, killing protester Heather Heyer.

"Charlottesville was an indication we knew even on the NSC side, for the policy shop, that we needed to think more aggressively about this rising domestic terrorism threat," Ali said. "When I left in the summer of 2018, that to me is when the far-right threat really started to rise in prominence and almost, you can make the argument, sort of eclipse the international terrorism threat as the number-one priority to the homeland."

While the FBI and Justice Department have declined to identify how many ongoing domestic terror investigations are being pursued by agents and prosecutors around the country, in testimony on Capitol Hill last September, FBI Director Christopher Wray said the bureau was already experiencing a higher number than the 1,000 domestic terror cases it typically tracks each year.

Wray added that what the bureau categorizes as "racially motivated violent extremism" amounted to the "biggest bucket" of cases the bureau had opened at that time.

Combating the threat

In recent years an increasingly contentious debate has emerged between lawmakers and law enforcement officials over the best approach to combating the growing domestic extremist threat -- an issue that's been made all the more urgent following the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Some lawmakers have proposed passing a new domestic terrorism statute intended to empower law enforcement to more aggressively investigate and prosecute members of extremist groups in the U.S., an approach backed by the leader of the FBI's top union for agents following the violent Charlottesville rally in 2017.

"Congress should amend the U.S. Code to make domestic terrorism a crime subject to specific penalties that apply irrespective of the weapon or target involved in the crime," former FBI Agents Association President Tom O'Connor wrote in an op-ed at the time. "Specifically, this legislation should make it a crime for a person to commit, attempt, or conspire to commit an act of violence intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population or to influence government policy or conduct."

While domestic terrorism was previously defined under the Patriot Act as criminal acts "dangerous to life" that appear "intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population or to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion," supporters of a new domestic terror law argue that such a definition is too narrow and note that there is no chargeable criminal offense specifically governing acts of domestic terror. Instead, federal prosecutors can open so-called "domestic terrorism investigations" -- but when bringing charges against defendants they typically rely on hate crime, firearm violation or assault statutes.

However, proposals to amend existing domestic terrorism statutes have set off alarm bells among civil liberties advocates, who argue the FBI and other agencies already have more than enough authority under the law to pursue violent extremists in the homeland.

"Which groups are you going to designate as terrorist organizations?" said Faiza Patel, co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. "Today you might say, well, a President Biden could designate the Proud Boys as a terrorist group and then anybody who provides them with support could be prosecuted. But the next president, or the current president for that matter, could under a similar law designate antifa as a terrorist group, or he or she could designate Greenpeace as a terrorist group."

Former federal prosecutor Richard Zabel, in a recent Washington Post op-ed, argued that rather than designating specific groups, Congress could tailor a law that specifically defines acts of domestic terror to go beyond those "dangerous to life" and encompass acts such as "threats, non-life-threatening physical assaults, damage to property and other acts intended to intimidate or coerce." Such a definition, Zabel said, would allow prosecutors to bring domestic terror charges against those involved in acts like the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol.

Patel said a key challenge for Garland and other Justice Department leaders will be exercising discretion in how they distinguish between violent actors and the broader ecosystem and movements under which they're operating.

"It's obviously not tenable for the Justice Department to treat everybody who believes the election was stolen as a domestic terrorist," Patel said. "He has to and I'm sure he will, you know, draw lines between those who are plotting violence or engaged in violence and those who are actively supporting acts of violence -- but he has to be able to distinguish between those people and the broader, like it or not, political movement."

It's not clear, after decades of service both as a prosecutor and then on the federal bench, where Garland might stand on the issue.

President Joe Biden has made it clear that confronting domestic terrorism is a top priority for his administration, even using his inauguration speech to decry "a rise in political extremism, white supremacy [and] domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat." In the first days of his presidency, he ordered Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines to conduct a domestic terror threat assessment in coordination with the FBI and Department of Homeland Security that the administration could use to shape its policies on the issue.

But due to a delay in their confirmation hearings, that review has gone on a month now with neither Garland nor Biden's deputy attorney general nominee, Lisa Monaco, in place. Meanwhile, the department's prosecutors have proceeded with their pursuit of those responsible for the Capitol attack.

Neil Eggleston, who worked alongside Monaco while serving as White House counsel under President Barack Obama, told ABC News that Garland's experience in Oklahoma City will immediately bring him credibility as he steps in to supervise the department's Jan. 6 probe.

"Obviously it's not completely parallel, but [it's] the kind of painstaking accumulation of evidence that they had to do in order to identify the perpetrators," Eggleston said of the process of preparing a case for trial. "I think there are going to be some techniques that were not around back when he did Oklahoma City, but the basic concept ... is pretty much the same. And I think he's the right guy to lead this."

Beyond the investigation into the Capitol rioters, experts say that Garland's approach to tackling the country's broader domestic terror problem will likely define his tenure and legacy.

"At a strategic level, this is going to be one of the biggest challenges for the administration," Ali said. "And it's not going to happen overnight; it's going to take probably a year or two to get all this stuff lined up and pointed in the right direction."