Refugee mothers seek safety on Greek islands with 'traumatized' young children

LESBOS, GREECE -- When airstrikes intensified on their village in Deir Ezzor, Syria, Fatima al-Abdallah and her children left home without a moment to pack a suitcase. They fled along the Euphrates river, sleeping in the grass as they went. While war continued to ravage their country, they journeyed to Turkey before heading to the Greek island of Lesbos.

“There was no longer a shelter for us to hide,” al-Abdallah told ABC News during an interview last month. “So I had to come here for the sake of the children.”

Al-Abdallah now lives with nine of her children in a small tent inside a larger communal tent in the Moria refugee camp, the largest on the Greek island of Lesbos. Her family is part of a growing wave of women and children who have flooded the Greek islands recently. In the last four months of 2017, nearly 15,000 migrants and refugees arrived on the Greek islands from Turkey compared to nearly 10,000 in the last four months of 2016, according to the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR). While a little more than half of arrivals in the first half of 2017 were women and children, the number increased in the second half when women and children made up nearly two-thirds of arrivals, according to UNHCR. Many of the women are single mothers who fled areas with recent fighting in Syria such as Raqqa and Deir Ezzor.

“Some of them told us that this was the first opportunity for them to leave,” Boris Cheshirkov, a UNHCR spokesperson, told ABC News. “Some are trying to reunite with their spouses in Europe.”

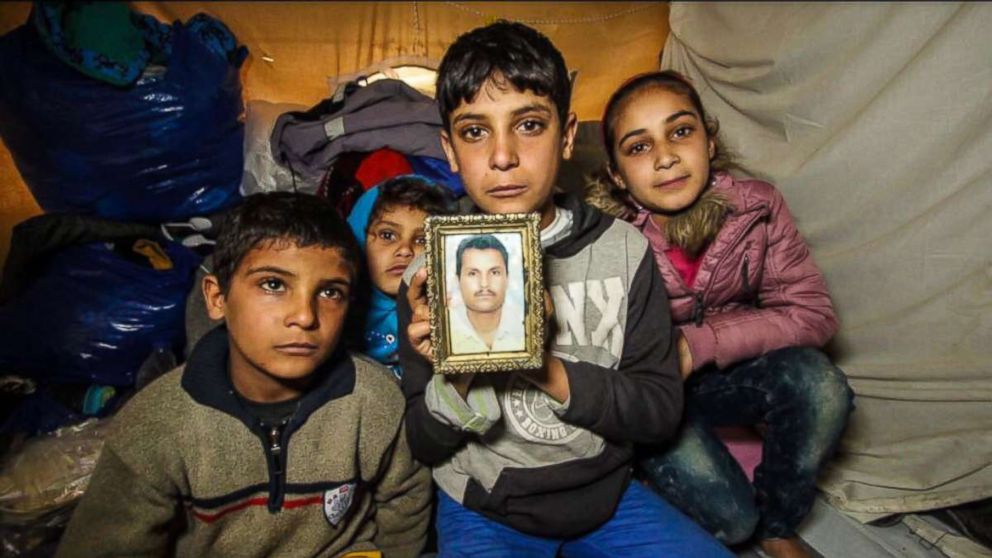

ABC News spoke with dozens of recent arrivals, most of whom fled from Deir Ezzor in Syria. Some of the women said they escaped alone with their children because their spouses were killed in the war or detained.

That is the case for al-Abdallah, who said her husband was detained by the Syrian government about four years ago. Al-Abdallah said she was not able to see him after his detention or even find out exactly where he was being held. Then one day she received some of his belongings from the Syrian authorities: an ID card, a wallet -- and a death certificate.

“We didn’t even get to see his body,” said al-Abdallah’s 14-year-old son, Mahmoud Emhemd.

Al-Abdallah said she doesn't know what to think; she has no idea if her husband is dead or alive.

“I don’t know if they just gave us the death certificate so that we would stop asking what happened to him,” she said. “I still have hope and I’m asking about him, but we haven’t been able to find out what happened.”

She pointed at her 4-year-old son, Majed, adding, “He was 7 months old when they detained his father.” Majed is too young to remember what his father looks like, yet sometimes he dreams about him, his mother said.

At the end of a muddy passageway in the camp, not far from where al-Abdallah lives, is a small tent, which is home to Aziza Hommada, also a single mother. She escaped from the same village in Deir Ezzor as al-Abdallah. Hommada is five months pregnant and lives with her six children in the tent.

In Syria, the family lived under ISIS rule. During that time, life was expensive and access to basic health care was limited, said Hommada. And when ISIS fighters carried out executions, the family was forced to watch, she said.

“They would kill people and drag them in the street in front of us,” she said. “They would cut heads off and hang them up in the streets. When they were going to cut someone’s hand or head off, they’d collect everyone and say, ‘You have to watch.’”

The journey to Europe involved several stops inside Syria and many dangers. After the family escaped airstrikes on their neighborhood, they made a stop in a village where ISIS had been defeated. They rented a house for a month, but couldn’t afford to stay there. Instead, they moved into an abandoned house that ISIS had used as a prison and headquarters, Hommada said. The house was messy, filled with pieces of metal, nails and screws. The walls were black from soot. ISIS used to produce explosives there, she said. One day, the family lit a fire in the garden so that they could bake bread. Suddenly, Hommada said, they heard a loud bang. She looked up and saw that the face of her youngest son, 4-year-old Yousef, was filled with blood.

“He was injured by a landmine. We started screaming thinking his eye was destroyed, but luckily the shrapnel only hit his eyelid. He was also wounded in the foot,” said Hommada, pulling her son’s sock away to show ABC News the scar.

During the escape from Syria, the family was separated. Her husband left to pick up his sister from another Syrian village, said Hommada. Government forces then launched an offensive on the sister’s village and her husband never came back.

Hommada said she waited in Syria for about a month, trying to learn any news about her husband. Eventually, relatives helped her and the children escape the country. Months later, she still doesn’t know if her husband is alive, she said.

“I hope that I will find out what happened to him before the baby is born,” said Hommada. “During the day I’m busy. At night, I start thinking and crying.”

Hommada's 14-year-old son, Anas, said he worries about his dad all the time.

“My mental state will suffer until I find him,” he said. “The first thing I think about in the morning is to find my dad with us and before I go to sleep I wish our dad was with us.”

His younger sister Bushra, 12, said she feels the same way.

“How are you supposed to live without your father?” she asked.

After ABC News left Lesbos, Hommada and her children were moved to the Kara Tepe camp, which is home to some 1,000 people and is not overcrowded. In comparison, the Moria camp houses about 2,000 people over its capacity. It’s difficult to keep up with the number of arrivals, said the director of the camp.

“Everyone talks countless hours on the phone, to get everything in order, to strive, but honestly I say to you the problems that we have here are huge,” Giannis Balpakakis, the director of the Moria camp, told ABC News. “Why? Because constantly we have new people. There is this stress, to welcome today 100 people, then 200 tomorrow, then another 100.”

In response to the recent increase in women and children arriving on Lesbos, Doctors Without Borders opened a pediatric medical clinic right outside the Moria camp in late November. There, they treat pregnant women and children, mainly with diseases and conditions related to the cold weather and lack of hygiene in the camp: Diarrhea, common colds and burns from fires that people light to keep warm in the winter months.

The clinic sees approximately 50 children and around eight to 10 pregnant women a day on average. Some of the women have just found out that they are pregnant, while others are eight months pregnant when they cross the border, said Mardjan Abidian, who is a cultural mediator at the clinic.

“Many of them also have a bunch of other small children to take care of. They are holding on with the last of their power,” she said, adding that the women and children who arrived recently are very distressed. “These are children whose schedule has been changed, whose system has been changed. They don't have the predictability of their daily life anymore. Pregnant women sleep in tents without a heater or in a container that they have to share with a lot of other people with a lot of stimuli around them. They have to walk to the toilet. There's cold water there. So it's very hard under these conditions.”

In a grove of trees outside of the Moria camp, some estimated 300 families live in tents. The area serves as an informal refugee camp, where some have chosen to stay because they feel safer and have more privacy than in the official Moria camp. Ratibah Subhi, her husband and their six children are some of the people who have chosen to stay here among the olive trees. When ABC News visited the family in mid-January, they said they had been in Lesbos for about 24 days. They escaped from airstrikes in their hometown of Deir Ezzor in Syria in November, said Subhi.

“There were planes above our heads attacking us,” Subhi told ABC News. “Sometimes when a plane flies by now, the children get scared and start to cry. They’ll sit next to me and scream and I’ll tell them, ‘This plane won’t attack us.’ They are traumatized. They saw bombs and rockets and they saw people getting killed in front of them.”

Her two youngest children, twins who are nearly 2 years old, are ill. One of them often gets a fever and stomach aches, and the other has a heart condition, Subhi said.

“When it gets cold they get sick,” she said. “Their lips even turn blue.”

Her own health has suffered as well. She was four months pregnant, but had a miscarriage recently -- because of the cold and the exhaustion, she said. Before her latest pregnancy, she had several Caesarean sections. The wounds get infected and still cause her pain, she said. The cold weather makes it worse, and the family has no heating in the tent, she added.

Subhi said she has no idea for how long she has to live in the tent and wait on the island. In some ways, living with that uncertainty under these conditions is worse than life in Syria, she said. Still, she said she can’t imagine ever returning to her country.

“Even if Syria goes back to the way it was before the war, we wouldn’t feel like going back,” she said. “Because of what we saw.”

ABC News' Bruno Roeber contributed to this report.