Are record corporate profits driving inflation? Here's what experts think.

While sky-high inflation has crunched budgets for essentials like gas and groceries, many large corporations have reported record profits, eliciting anger from some everyday people and public officials over price-gouging.

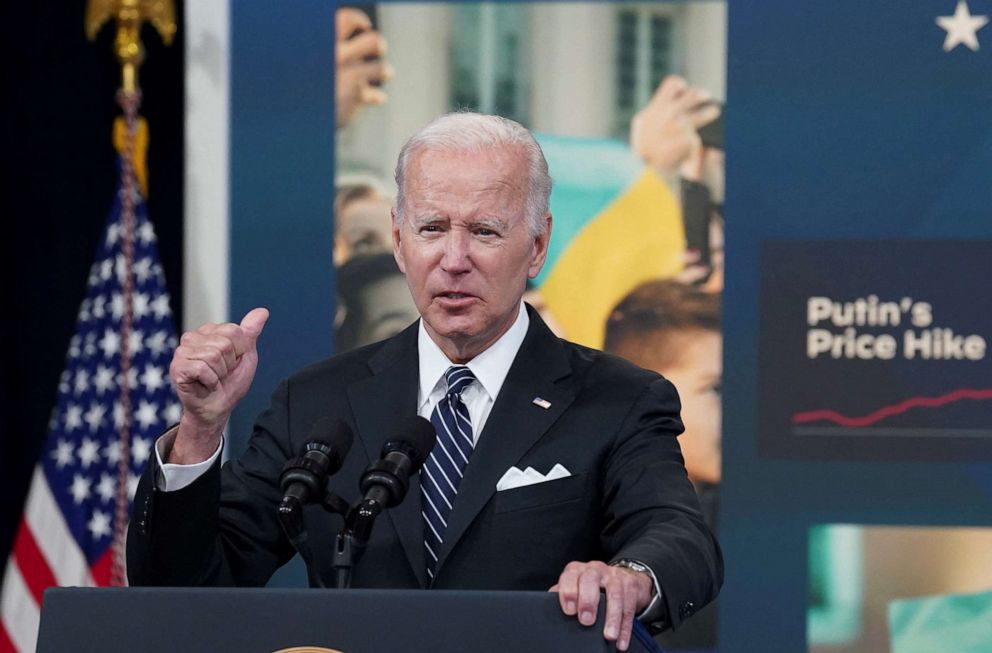

Such frustration recently rose to the fore over eye-popping gas prices. Earlier this month, President Joe Biden sent a letter to major oil refinery companies accusing them of taking advantage of the market environment to reap profits while Americans struggle to afford gas.

The problem extends well beyond gas, according to progressives like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., who backed a bill last month that would empower a federal agency and state attorneys general to enforce a ban on excessive price hikes.

But economists disagree over the role that elevated corporate profits have played in driving inflation, as some say they account for more than half of the increase in prices while others say they have caused little or none of the hikes.

Some who do blame corporate price-gouging for a portion of the price increases said it arises from market concentration that allows a handful of dominant companies in a given sector to raise prices without fear of competitors undercutting them with lower-priced alternatives. But others doubt that explanation, noting the unlikelihood that a major shift in corporate concentration took place over just a couple years amid the pandemic.

The divide among economists also owes in part to mixed assessments over whether corporate profits have driven inflation or merely responded to it, since a global market rocked by pandemic-induced supply-demand shocks has created a favorable environment for many companies to hike prices.

“It’s a very intense time for people and their pocketbooks — I understand why these debates are very heated,” Michael Konczal, the director of macroeconomic analysis at the Roosevelt Institute, told ABC News. “A lot of people are on team demand, team supply, team transitory, team corporate gouging.”

“I think there's reflection that there are a lot of causes,” he added. “Even as those causes are evolving.”

Economists agree that inflation owes at least in part to a supply-demand crunch amid the pandemic in which federal stimulus helped consumers purchase goods at the exact time that they got stuck in a production and distribution bottleneck, experts told ABC News.

But economists disagree over how much that supply disruption has contributed to inflation, as opposed to the market environment that it has created, in which companies could raise prices knowing that their competitors faced similar supply shortages that prevented any of them from flooding the market with cheaper alternatives.

“In the case of sector-wide supply chain issues, as during the pandemic, firms know that their competitors face the same bottlenecks as themselves,” Isabella Weber, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, told ABC News. “The public, too, is aware of the supply issues. Taken together, this presents a pretext to increase prices.”

Josh Bivens, the director of research at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, published a study in April that found corporate profits accounted for more than half of the price growth between 2020 and 2021 in the non-finance corporate sector, which makes up about 75% of the private sector.

But the surge in profits stems from a confluence of factors that is likely unique to the pandemic-era economy, Bivens said.

“I view the big fattening of profit margins that boosted prices as another shock, like the pandemic, like the oil price shock,” he said.

A separate report from the Roosevelt Institute, a liberal think tank, found that companies that imposed higher-than-typical markups before the pandemic were likely to be the same companies that hiked prices during the pandemic, suggesting that certain firms exploited their market position to raise prices during the pandemic. In other words, if a company could mark up prices before the pandemic without fear of competitors, it could do so during it.

“This makes us think there’s a small but real role for corporate power to be involved with the increase in inflation,” said Konczal, the economist at the Roosevelt Institute, who co-authored the study.

But other experts contested the explanation that market power or greed has driven companies to exploit market conditions during the pandemic, arguing that high prices reflect forces of supply and demand rather than any misdeed on the part of a company.

Michael Faulkender, a professor of finance at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business, compared companies charging high prices to an individual who puts his or her home on the market at a favorable time.

“Let’s say I bought a house five years ago, and I’m looking to sell it for whatever reason. Do I price it at what the market will bear or what I bought it for plus a politically correct predetermined markup?” he said. “I’m going to price it at what the market can bear.”

The high prices at the grocery store or the pump are the expected outcome of a market in which individuals have ample money to spend but few products to buy, Faulkender said.

“The limited supply available goes to those with the highest value,” he said. “The profits then generated are a consequence but not the cause.”

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen appears to share a view that minimizes the role of corporate profits as a cause of inflation. Earlier this month, at a Senate Finance Committee hearing, Yellen refused an opportunity to blame price hikes on company greed, citing supply and demand as the primary explanation.

Bivens, the economist at the Economic Policy Institute, criticized the value of recent price hikes as market signals, which typically tell market actors where to invest resources. The pandemic-induced shift to goods like Pelotons and lumber and away from face-to-face services is unlikely to persist for a prolonged period, he said.

“The line between price gouging versus useful market signals is always a pretty tough one,” he said. “I don’t think these are useful signals.”

Where economists come down on corporate profits informs what, if anything, they think should be done about it. Bivens said he supports a tax on windfall corporate profits, a version of which was proposed by Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt.., in March. Meanwhile, Faulkender said the government should promote greater supply, especially in the energy sector, as a key way to address high prices.

Personal finances nationwide will depend on the outcome for corporate profits, Konczal said.

“Whether they’re naturally competed away on their own, whether policy intervention is going to help nudge the process along, it does have important consequences for inflation and everyday people’s pocket books,” he said.