As recently discovered unmarked Indigenous graves in Canada nears 1,000, activists demand justice

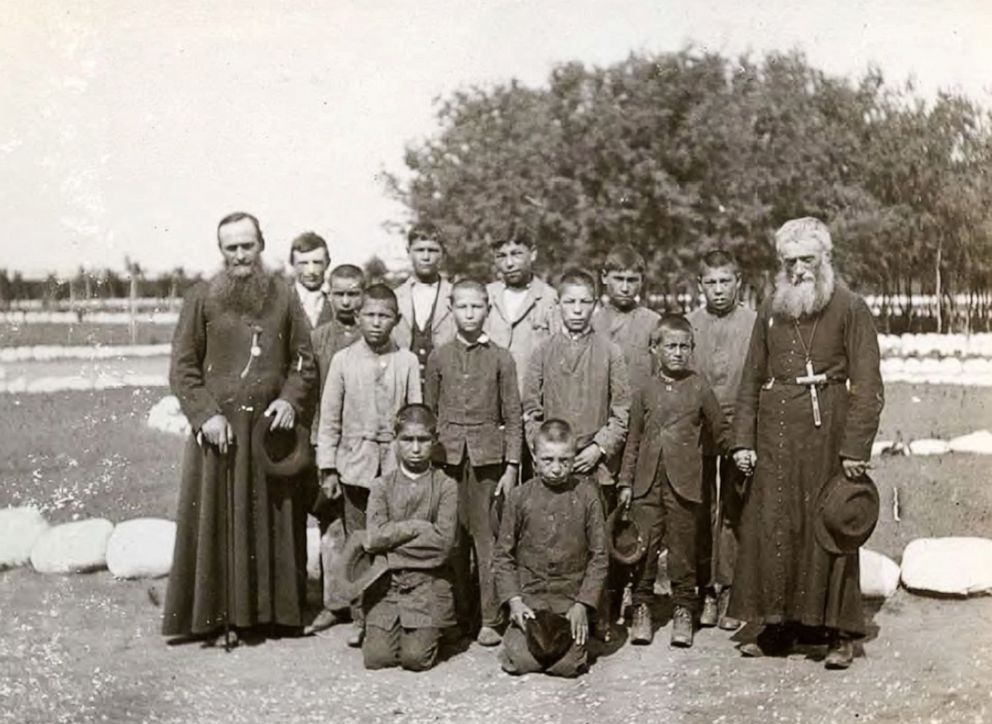

For decades, beginning in the 1800s, thousands of Indigenous peoples from Canada were taken from their homes and families by the Canadian government, shipped thousands of miles away in some cases and placed into so-called residential schools.

The stated purpose of the schools, some of which date to the 19th century and the last of which closed in the 1990s, was assimilation -- ridding the students of ties to their communities and instilling European culture, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC).

There were reports from the TRC -- a commission funded by the Canadian government as part of a legal settlement to address the wrongs of the system -- of thousands of instances of abuse and mistreatment against students and many of the students did not make it back to their homes in what advocates for the Indigenous population and officials alternately term "injustice," "systemic racism" or even "genocide."

There have recently been a number of reminders of that grim past -- one which advocates say continues to haunt Indigenous communities.

Another 182 sets of human remains were found on June 30 near the former St. Eugene's Mission School for Indigenous children in the community of Aqam,, bringing the total found in the country in recent days to nearly 1,000.

A week earlier, 751 unmarked graves were found at the cemetery of the former Marieval Indian Residential School. It is unclear how many of the students died or what the causes of death were.

“It’s opened fresh wounds for a number of people,” said David Pratt, the second vice-chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations. FSIN is an advocacy organization that represents 74 First Nations in the implementation of treaties that protect Indigenous people and land.

The site at Marieval has the largest number of graves connected to a residential school discovered in Canada so far, according to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), which archives and compiles the complete history of Canada's residential school system.

In a June 24 statement, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sent his condolences to Indigenous groups across the country following the Marieval discovery.

“They are a shameful reminder of the systemic racism, discrimination, and injustice that Indigenous peoples have faced – and continue to face – in this country,” the statement read. “Together, we must acknowledge this truth, learn from our past, and walk the shared path of reconciliation, so we can build a better future.”

However, Stephanie Scott, executive director of the NCTR, said that these problems continue to harm Indigenous communities to this day.

“The residential school system has impacted generations,” Scott said. “Take action, take responsibility to learn the true history, seek out survivors and indigenous people and start that dialogue.”

What are residential schools?

What are residential schools? In a 2015 report, the NCTR said there had been 150,000 First Nation, Métis and Inuit students in the residential school system. The first schools of this kind were formed in the 1860s and lasted all the way until the final school, Gordon Indian Residential School, closed in the late 1990s.

About 139 Indian residential schools were identified in the 2006 Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement.

For decades, Indigenous children in both Canada and the United States were taken from their families and sent to boarding schools, sometimes thousands of miles away, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Scott, whose mother was a student in one of these schools, said that many students were beaten and abused for speaking their language or practicing Indigenous traditions. She said there have been reports of physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and illness.

“We've even heard stories about young girls getting pregnant and the children being born and putting into incinerators,” Scott said. “We've heard stories of children being hidden in walls. We went to the community one time where there was a caretaker’s house where we found this strap that was covered in blood.”

The official report from TRC reiterates stories of children being strapped, beaten, and forced into crawl spaces.

Scott said her mother got pregnant while attending the residential schools, and child welfare authorities took her away.

“I was adopted out into a community with that forced assimilation and those policies where I didn't have access to my culture and community,” Scott said. “I grew up without my language.”

Why are there so many unmarked graves?

Many students never returned home from the schools, according to the NCTR. The NCTR reports that the deaths of more than 4,000 children have been connected to residential schools, as graves of young children continue to be uncovered -- but Scott said that there are likely more left to be found.

Researchers have been used ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to discover unmarked burials, like the St. Eugene's Mission School and the Marieval Indian Residential School.

In May, researchers also found the remains of 215 students at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. Some children buried onsite had been as young as 3 years old.

The NCTR has found that many of the children died from illness and malnourishment, among other causes. Scott said she’s heard stories from old school attendees who claimed illnesses and injuries went untreated.

It is unclear how all of the children have died, and who they were.

For many, the discovery of graves is a time of grief, as many can remember the days when residential schools were still around. Pratt said the discoveries of unmarked graves bring up a lot of emotion, trauma and heartbreak for those who’ve been lost and called on the Canadian government and the Roman Catholic Church to help.

“They need to apologize and they need to take responsibility and ownership on the trauma and the chaos they've caused amongst indigenous peoples of this land,” Pratt said.

Who has taken responsibility for these?

The residential schools were run by the Canadian government, the department of Indian Affairs and churches, including the Roman Catholic Church at various points in their histories, which has been connected with the recent unmarked grave discoveries.

The St. Eugene's Mission School, for instance, was operated by the Roman Catholic Church from 1912 to 1970. The Marieval Indian Residential School was also run by the Church from 1899 to 1997.

The Kamloops Indian Residential School was run by the Church until the late 60s when it was taken over by the federal government.

Pope Francis plans to meet in December with Indigenous survivors of the residential school system from the First Nations, Metis and Inuit groups.

But the Roman Catholic Church has yet to issue a statement on the discoveries. The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops did not respond to ABC News’ requests for comments.

According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, the United States also had more than 350 government-funded boarding schools across the US.

In 2000, U.S. Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Kevin Gover apologized for the trauma and violence against children at the American residential schools.

Trudeau, in his recent statement following the discovery of the Marieval graves, said he promised to help Indigenous people in Canada heal.

“The government will continue to provide Indigenous communities across the country with the funding and resources they need to bring these terrible wrongs to light,” the statement read. “While we cannot bring back those who were lost, we can – and we will – tell the truth of these injustices, and we will forever honour their memory.”

In the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history, reached in 2006, Canada promised funding, support, and the formation of federal commissions to help the community heal. The settlement of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement was a step, activists say, but many are demanding stronger action.

High incarceration rates, poverty, addiction, trauma, and climate change have plagued Indigenous communities, and Pratt links them to the lasting effects of residential schools.

Scott agreed, saying the unmarked graves have opened up an opportunity to discuss what Indigenous communities are owed and what they continue to experience as a community. Scott said education and dialogue about these atrocities are just the first steps.

“Canada must claim responsibility for the genocide and it has to show a commitment to sharing these truths with all people in Canada,” Scott said.