Protests in US shine light on Germany's struggle with racism and police violence

BERLIN -- Six years ago, Jeremy Osborne moved to Berlin to pursue a career as a professional opera singer. When he's not using his velvety baritone to perform in concerts and choirs, the black 33-year-old Arkansas native closely follows German and U.S. politics.

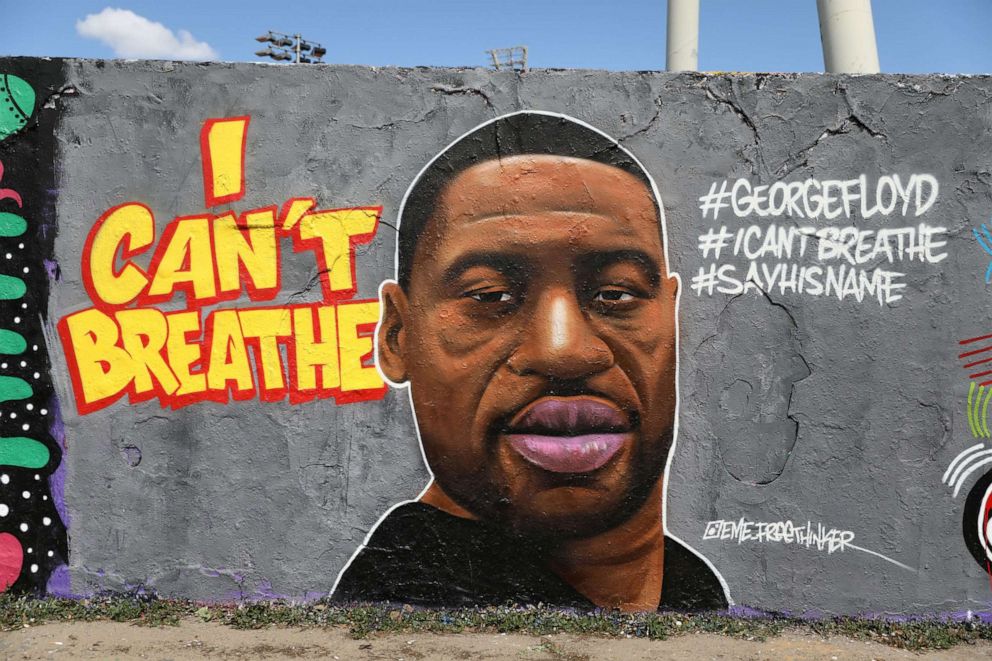

Along with 10,000 fellow protesters, Osborne attended the large demonstration in central Berlin on June 6 to protest racism and police brutality in the U.S. in the wake of the death of George Floyd. With an estimated 150,000 people attending similar protests across Germany, Floyd's death has called attention to anti-black racism and police violence against minorities in Germany.

"The mainstream political discourse is much more comfortable discussing racism in another country than it is discussing racism that actually occurs in Germany," he told ABC News.

For Osborne, the issue of race in Germany is personal.

He's currently involved in a lengthy legal dispute with a Berlin gym that accused him of insulting another patron at a time when he was out of the country. He filed two complaints for discrimination and when he tried to return to the gym, the police were called.

"They thought I faked the legal document that said I had a right to use this gym. One said, 'I could have printed something off my computer too,'" Osborne told ABC News. "I don't think they would have treated me like that if I was white."

And Osborne, who is one of 1 million black people in the country, is not alone.

According to the German Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency, (ADS) the number of racial discrimination cases reported in the country is on the rise. The 2019 data, presented last Tuesday, shows a 10% increase from the previous year, with racial discrimination cases making up 33% of those dealt with by the agency.

Germany has an "ongoing problem with racial discrimination and does not give enough consistent legal support to victims," Bernhard Franke, head of ADS, said while presenting the report.

Taking a closer look at police violence

Police brutality in the U.S. has put a spotlight on the behavior of German police, including several high-profile cases. In 2005, the body of an asylum seeker from Sierra Leone, Oury Jalloh, was found burned in a cell; he was in police custody in Dessau with his hands and ankles chained to a mattress. Authorities said Jalloh had taken his own life, but circumstances remained murky and some activist groups suspect a police-violence cover-up and called for independent investigations on illegal police work, including Amnesty International.

A new medical report released in 2019 revealed that Jalloh had broken bones that he could not have inflicted on himself. The European Network Against Racism said the new report indicates that "police killed Oury Jalloh," reported Deutsche Welle.

In 2001, a Cameroonian asylum seeker, Achidi John, died after being given emetics, a drug that causes vomiting, while in police custody in Hamburg. In 2016, Iraqi refugee Hussam Hussein, was shot and killed by police outside a Berlin refugee shelter.

Discussion of racism in Germany's police force has made its way into the political realm in recent days. The head of Germany's center-left Social Democrats, Saskia Esken, said in an interview with newspapers from the Funke media group that there was "latent racism in the ranks of the security forces" in Germany and called for an overhaul of excessive violence and racism by officials.

Police unions fired back.

"We think your statement is wrong and unnecessary. In our view, there is no reason to link the events in the United States with local conditions," Dietmar Schilff, deputy chairman of the Federal Police Union (GdP), retorted in the German paper Spiegel. Similarly, a politician from Angela Merkel's Christian Democratic Union, Thomas Blenke, said, "Germany is not the USA. We don't have a racism problem in the police."

Yet recent high-profile cases present a different story.

The most famous case of alleged police misconduct is that of the National Socialist Underground murders that took place between 2000 and 2007, in which a neo-Nazi cell of three people in the eastern German city of Jena killed 10 people, nine of whom were from immigrant backgrounds. During the duration of the cell's criminal activity, however, investigators targeted the Turkish gambling mafia and did not look into a possible right-wing extremism motive. Victims' relatives faced allegations that their family members had been involved in criminal activity and the deaths of their loved ones.

Since then, Germany has been rocked by a series of violent crimes by right-wing extremists, as the political party supporting an anti-Islam stance, Alternative for Deutschland, gains traction. In February, a gunman in the town of Hanau, who had a website on which he published xenophobic views, opened fire in and around two hookah bars, killing nine people of Middle-Eastern descent. Last June, pro-refugee politician Walter Luebke was shot outside his home. In 2018, right-wing extremists held xenophobic riots in the city of Chemnitz.

The effects of a society increasingly tolerant of right-wing extremism trickles into government authorities such as the police force, says Biplab Basu, founder of Campaign for Victims of Police Violence (COP) and a counselor at Reach Out, an organization that provides legal assistance and counseling to victims of racist, right-wing and anti-Semitic violence in Berlin.

"This can be seen within the police department," Basu told ABC News. "I have a feeling that the increase in incidents is because the white supremacists are very much at work."

Difficult to prosecute

Most of Basu's clients at Reach Out are what he calls "visible minorities," those from minority backgrounds who have a skin color that contrasts with that of Caucasian Germans. This population, he said, most frequently experiences racial profiling by the police, despite a constitutional ban.

Yet prosecuting police officers on the basis of racial discrimination is next to impossible, he said.

"We tell our clients, if you want to do something, you can go against it in the form of an official complaint and we will try to provide you with legal help, and then we'll see, because in Germany one could say that 98 percent of the cases are dropped by the prosecutor's department," Basu said.

Sebastian Bickerich, spokesman for the German government's Anti-Discrimination Agency, told German news outlet Deutsche Welle that the country lacked both "systematic gathering of racial profiling cases and clearly defined jurisdictions and complaint structures."

Yet some headway is perhaps being made. The Federal Ministry of the Interior and Justice are "currently in the conceptual development for a study on racial profiling in the police," an interior ministry spokesperson told the German paper Die Welt on Thursday. Further details have not yet been announced.

Speaking out

However, some changes are perhaps afoot. For Basu, the high turnout at the Floyd protests was a milestone for minorities in Germany who face discrimination.

"One could say for the first time that black people and people of the minority communities came out in the open, spoke out and showed the authorities that they are not going to accept brutality," he said.

In this case, the connection between the events in the U.S. and those in Germany was shockingly apparent.

"These young people were able to assess the situation and realize that it's very important to show their solidarity with the people in the United States who are demonstrating against injustice and also voice their own anger against the injustice happening here," Basu said.

New hope also comes in the new anti-discrimination law passed in Berlin on June 6. It bans public authorities, including police and public schools, from discriminating against people based on skin color and gender, among other factors – and those who have been victims are entitled to compensation.

The new law replaces the less-comprehensive nationwide legislature, the federal General Equal Treatment Act (AGG) from 2006. Berlin is the first German state to pass the law.