Project Impact: 'Disease intelligence' and how the CIA traced epidemics out of Cold War Asia

As the CIA would later say, it all started "innocently enough" with unexplained school closings in southeast China in the winter of 1966. But then travelers entering Hong Kong began reporting that things were getting bad on the mainland, with a disease "raging" in one province.

By mid-January 1967, "the epidemic in Canton was out of control," according to a declassified article in the CIA's internal journal, referring to the city now known as Guangzhou. China's military took over hospitals in the region, but eventually the "entire public health infrastructure began to collapse."

"It is becoming increasingly evident that Communist China is being confronted with a serious disease control problem," an article in a 1972 edition of Studies in Intelligence reported.

"Factors suggest a breakdown of public health measures under the impact of mass movement of people, and perhaps the beginning of a series of new disease problems."

That epidemic was an outbreak of meningitis, scientists later determined, but it was also the beginning of a CIA program, one of the first in "disease intelligence," a boutique field of espionage and analysis that aims to uncover the signs before and consequences after a pandemic.

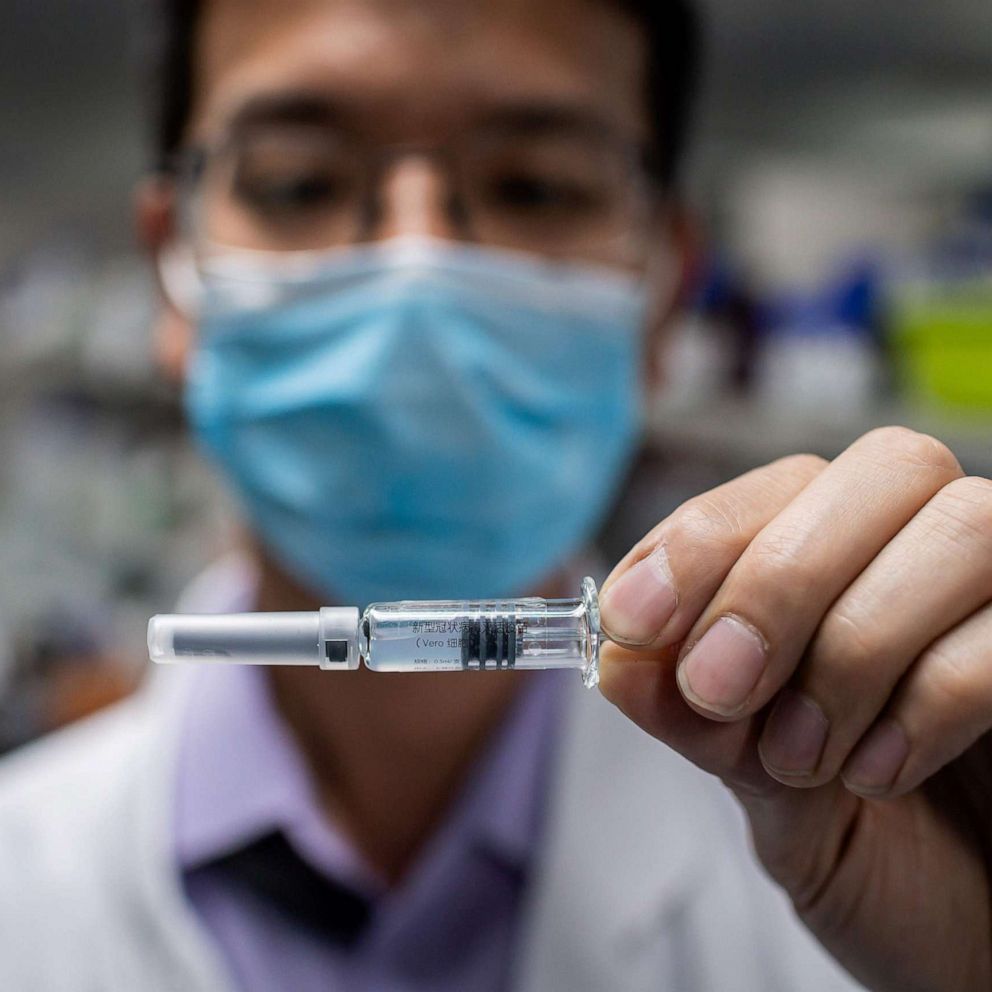

Disease intelligence is a field that's come to renewed attention in recent months as sharp questions have been raised about when the U.S. intelligence community understood the significance of a novel coronavirus festering in Wuhan, China, and when warnings first reached the White House.

ABC News previously reported that sources said a U.S. military intelligence department dedicated to "medical intelligence" sounded alarms as early as late November 2019, and information about the outbreak was included in the President's Daily Brief by early January. At the time of the ABC News report, the Pentagon issued a statement denying the Defense Intelligence Agency department had issued a "product/assessment" in November.

Darrell M. Blocker, a former senior CIA officer who was head of the agency's Africa Division during the Ebola crisis in 2014, said the CIA's mission in disease intelligence is similar today as it was more than a half-century ago and is twofold: Uncovering what's really happening on the ground in countries during epidemics that don't like to share that information and attempting to predict what effect it could have on U.S. interests in the region.

"There's a side to the [disease] research they don't want people to know about. That's where the intelligence comes in," said Blocker, now an ABC News contributor. A spokesperson for the CIA declined to comment for this report.

Blocker said now the U.S. intelligence community can call on its vast, 17-organization-strong apparatus to assess what a disease is doing and how local governments are reacting. But in the mid-1960s, a young CIA was only then starting to appreciate the value of disease intelligence. According to the 1972 declassified CIA article titled "Intelligence Implications of Disease," it began with Project IMPACT.

"The concept of this project -- forecasting disease problems and epidemics, and the assessment of their effects on military and civilian activities -- had hardly scratched the surface of implementations in the CIA's Office of Scientific Intelligence (OSI); but the opportunity was present in December 1966," the article said.

Disease intelligence 'going global'

While IMPACT was able to trace emergence of the meningitis outbreak in the closed communist country, in part by simply observing the movements of the Red Guard from one province to the next, it wasn't until the next outbreak, only months away, that the program expanded and "went global."

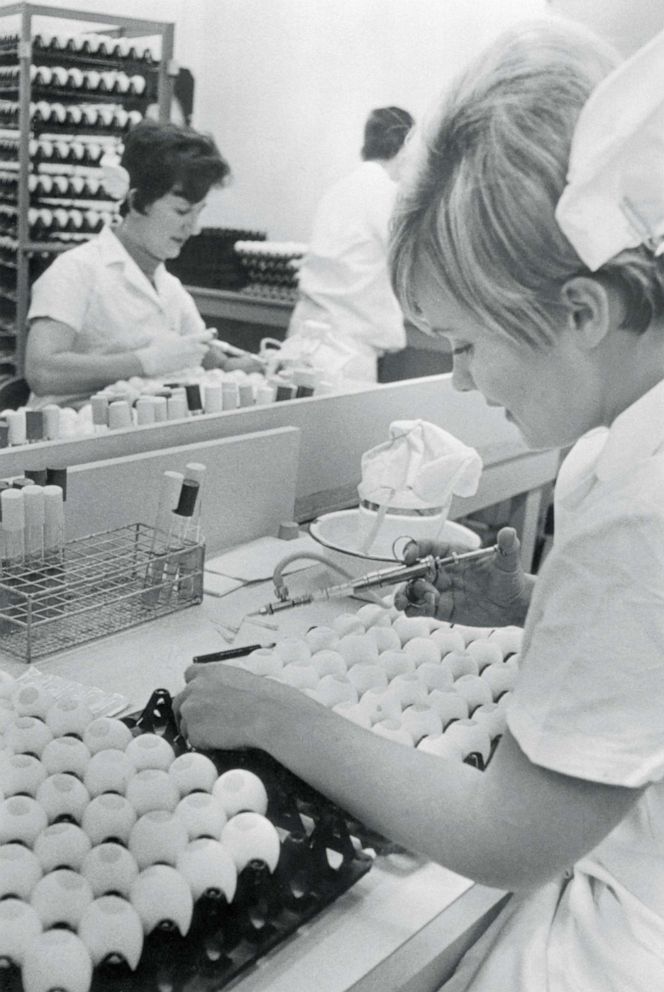

That's when a new strain of influenza appeared in Hong Kong and eventually snaked its way around the world. The virus "affected" one in four people on the planet, according to the CIA report. The 1968 flu pandemic is believed to have killed as many as 1 million people worldwide, including 100,000 in the U.S, as per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To monitor the flu’s progression, Project IMPACT folded in an ongoing CIA effort known as BLACKFLAG, which sought to "computerize disease information and derive trends, cycles and predictions."

Within weeks, scientists were able to determine it was, indeed, a new strain of influenza, which they named Hong Kong/A2/68. (While the CIA study, citing "various [Central Intelligence] Agency sources," states flatly that the virus "moved from China via travelers to Hong Kong," a World Health Organization report from 1969 on the virus' origins says it is "not certain" it came from mainland China.)

As experts gathered information on the new virus, the World Health Influenza Center in London made a dire prediction.

"The emergence of a new strain [of influenza] occurs every 10-15 years and together with rapid transportation, and in the absence of specific vaccines, leads us to believe that the disease may cause extensive outbreaks throughout the world in the coming months," the center said, according to the CIA study.

Stumbles in the Soviet Union, warnings in Vietnam

Though the center's warning discussed the "rapid transportation" of people, at the time it was still predicted that it would take some seven months for the new flu to hit the then-Soviet Union, America's arch-nemesis in the Cold War and the focus of so much CIA attention already.

Still, the Soviets weren't able to prepare, the CIA article said.

"[T]he Soviets continued to vaccinate the urban population (about 75 percent) with the standard A2 vaccine which was shown even in August, to have very little protective value against [the] Hong Kong flu (this decision later was reported to be based on their inability to make the new vaccine in less than a year and their gamble that A2 vaccine would help)," the report said. "By late January, the flu was present in many Soviet cities and incidence rates began to increase sharply."

The Soviets hid information about the disease and purportedly interfered with the efforts of health care workers on the ground, according to the study.

In an early echo of the Trump administration's attempts to brand the current novel coronavirus the "Wuhan virus," the Soviets reportedly referred to the disease as "Mao's flu," in a reference to the then-leader of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong.

As the disease spread south from China, and as the U.S. was in the middle of the Vietnam War, the CIA also used Project IMPACT to study the effects on the North Vietnamese army and the Viet Cong.

"Staff personnel of the Special Assistant/Vietnam Affairs (SA/VA) were consulted, and together with their data on traffic routes, troop concentration, and locations of waystations (Binh Trams), made it possible to construct a model of the direction of the influenza epidemic," the CIA article said.

With that data and by monitoring reports of sickness and military requests for medicine, the CIA determined that "incapacitation rates ranged from about 40 to 70 percent and there was very good evidence that except for the isolation and quarantine of patients, no capability existed to specifically protect their military personnel by mass vaccinations."

Using the data, the CIA also sent "a warning" to "indigenous intelligence teams operating in Laos and Cambodia to take special precautions during these peak influenza periods."

In the end, the CIA report suggested that Project IMPACT was most successful in simply showing the value of the aggregation of data to help predict the impact of outbreaks.

"Disease intelligence can provide an initiating and vital role in the more familiar political, military and economic categories of intelligence," it says.

It also offered a prescient warning, all the more pointed as the COVID-19 pandemic rages.

"The strain was not an unusually lethal one but it was only by chance that it was not," it says. "Such disease events undoubtedly will occur in the future, and they will be much nastier to all facets of human activity."