Dr. Ala Stanford isn't a pastor, though she's often at church and many in Philadelphia will tell you she is doing God’s work.

‘Hallelujah that God made a way,” said Gwen Carter as she waited to be tested for COVID-19 at Mt. Airy Church of God in Christ in Philadelphia on Friday.

Stanford has tested more than 1,500 deeply appreciative residents in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. She does not charge a dime.

In her hometown of Philadelphia, blacks make up the majority of the population, and nearly half of the coronavirus cases.

Amid concerns in the health care community about the disproportionate impact COVID-19 is having on black and brown communities, Stanford decided to take action.

“ I just couldn't be part of another town hall meeting or watch another webinar or talk about how pervasive the social determinants of health are and not do anything,” she told ABC News Live Anchor Linsey Davis.

As a pediatric surgeon in a private practice, she had access to some tests and PPE. She rented a van and loaded it up. Her husband got in the driver's seat and they hit the streets, making ‘house calls’ to residents who badly needed tests.

“We got our team together... it took literally 48 hours to get it together,” she said.

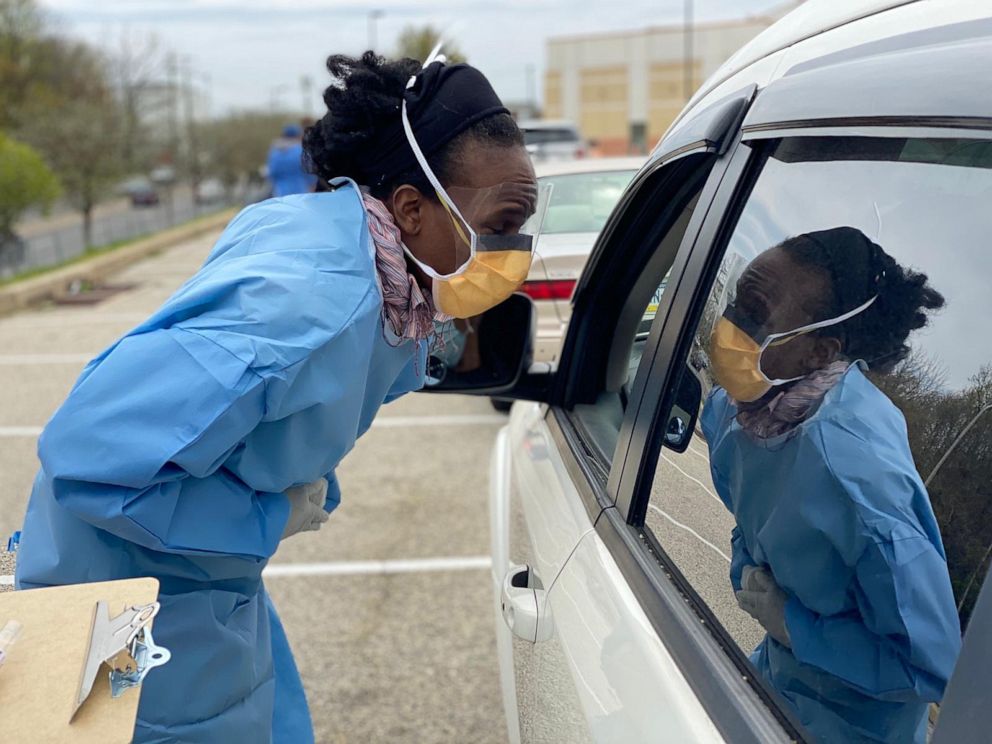

Just like that the “Black Doctors COVID19 Consortium” was born-- a group of medical professionals who assemble in church parking lots with protective gear, and highly-coveted coronavirus tests.

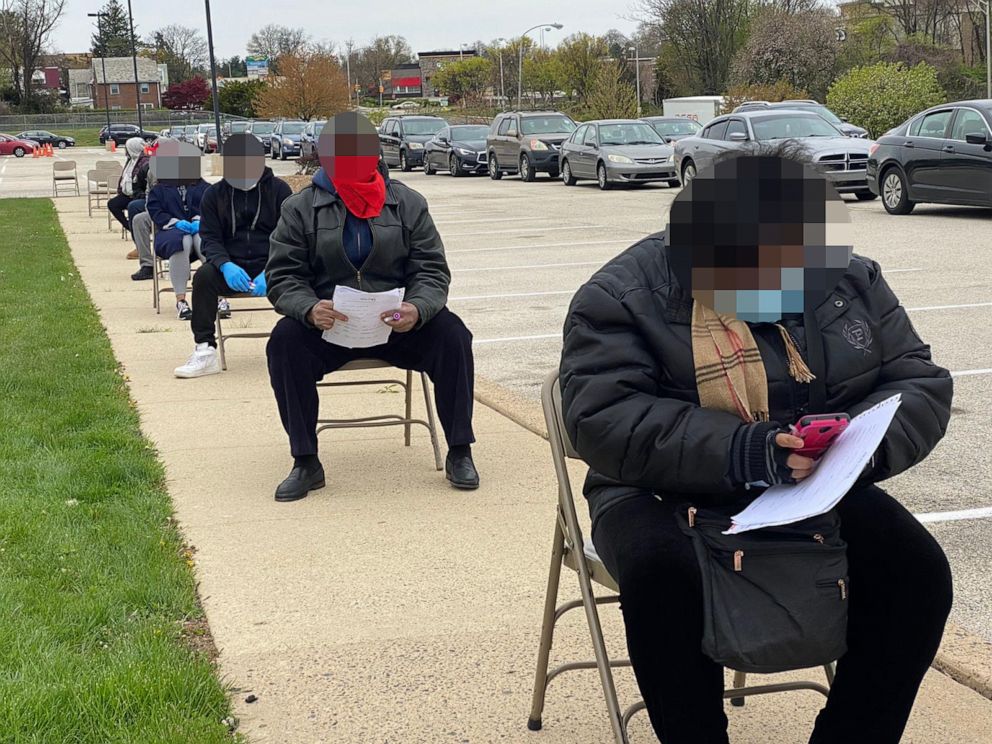

“We basically set up like a triage unit... every time we go we pack up everything it comes out of the van, we put everything up, we have a registration,” Stanford said.

By car, by foot, any way they can. Hundreds and hundreds show up.

They wait while socially distanced-- hoping they will be the lucky ones to get a test.

“The need is great... It just confirms to us that we’re exactly where we need to be testing these communities,” Stanford added.

They’ve hit more than half a dozen Philadelphia area churches, and Stanford and her team of volunteers don’t plan to stop any time soon.

Philadelphia is the birthplace of America, and home to the Liberty Bell-- but the city is also the poorest big city in the country-- according to the latest U.S. Census numbers, 24.9% of the city’s nearly 1.6 million residents live in poverty.

And those in poverty-- are having a significantly harder time getting access to tests.

Epidemiologist Dr. Usama Bilal is tracking who is getting tested by zip code.

He’s finding residents in Philadelphia’s wealthiest zip code--are five times more likely to get tested than those in North Philadelphia--home to some of the city’s poorest zip codes.

In North Philadelphia’s 19120 zip code-- just 2.7 per 1000 people are getting tested. The median household income there is around $37,000.

By contrast-- the 19102 zip code in Philadelphia’s center city has a median household income of more than $90,000. Testing rates there were 16 per 1,000 people.

“What we're finding in the Philadelphia area were the number of tests that were being conducted for professional people was about five or four times higher than in the poorer areas,”Bilal told ABC News.

Bilal says the trend is not unique to Philadelphia but exists in data found from New York to Barcelona, the number of positive tests tend to be higher in poorer areas.

“I call it the epidemic that never ends like wait one day we'll, we'll get out of coronavirus and sure we'll get out of it it was mitigated with something we could say with the vaccine etc. The epidemic that we really need to control long term is social inequality and that you know has centuries of history. It has many different intersecting axes so there is racism that is places that is classism, that is that is that is gender discrimination, there are many, many things going on there,” Dr. Bilal added.

Shortage of black blood donors

And now, the Red Cross flagging a new concern for blacks, a lack of blood donors.

The Red Cross tells ABC News prior to this pandemic blood donations from African Americans accounted for four percent of overall donations. But now-- the Red Cross is facing a dire shortage of donations from black donors.

Donations have dropped by 50 percent since the pandemic began, now accounting for just two percent of donations.

“People may be more concerned about going in to donate blood. And this is particularly problematic where in urban areas you're worried that you might be exposed to COVID-19 going in to donate blood,” Dr. Kimberly Whitley, chairwoman of the Sickle Cell Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia told ABC News.

Those donations are especially critical for those with sickle cell disease.

“African-American donors really need to come out and donate for children and adults living with sickle cell disease because their red cell units are going to be more likely to match those individuals who need the transfusions,” Dr. Whitley added.

Some 98% of those diagnosed with sickle cell disease are black. Many patients require blood transfusions once a month for their entire life-- that can’t be put on hold during the pandemic.

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia is one of the country’s largest comprehensive sickle cell centers, and they are donating thousands of masks and hand sanitizers to the families of young people with the disease.

Sickle cell disease patients have weaker immune systems-- making the importance of testing everyone who interacts with them for COVID-19 critical.

As it is well documented, not every COVID-19 patient has symptoms.

Pastor Alyn Waller, who leads Philadelphia’s largest church, Enon Tabernacle, was one of those.

Waller invited Stanford to test at his church, hoping to spread awareness of the importance of being tested.

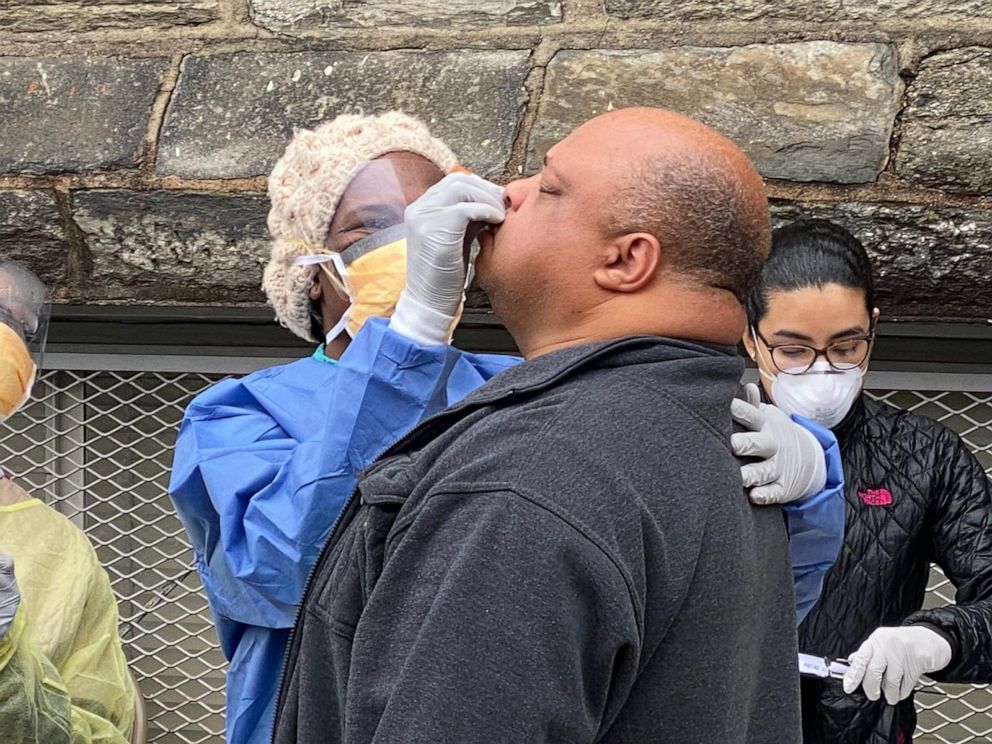

“I was just doing it not expecting to be positive. But, expecting to just show people that it really doesn’t hurt when it goes up your nose and so the last thing I expected.. Was to get a positive result,” Pastor Waller told ABC News.That day at Enon-- Dr. Stanford and her team tested 350 people. Their positive rate has been hovering between 18-20%.

“Now I think I’m on assignment, because I don’t feel bad and I can speak up for people that may not feel good enough to speak up,” Pastor Waller added.He believes the region, and the country needs more testing.

“Had I not taken that test, I would have been walking around shedding, and potentially infecting someone who would have worse experience with the same virus,” Waller added.

He is now preaching from home to his congregation of more than 12,000 people.

His message-- the black community must take responsibility for their own health.

“We know that when America catches a cold the black community has pneumonia. And so we have to take extra steps to make sure that the message gets out... it's a challenge to the system to recognize that disparities exist already. It's a challenge to our community to recognize that this is real, and we have to take responsibility for our own health,” Pastor Waller said.

Stanford says she’ll continue to test until she feels like Philadelphia officials are doing enough testing. She hopes doctors in other cities see what she’s doing, and get out there to help.

“For my doctors and friends in other cities, you can do this, you know you can do this, and hopefully you have the support of your local and state government. But if you don't, you can do it. It takes one doctor to decide that their practice is going to be about COVID-19, and you just do it,” Stanford said.

Stanford believes the government could set up a better testing infrastructure to help black communities in as little as a week, “I don’t see the resources, I don’t even see the cash, or the move into getting people tested,” she said.

Philadelphia Congressman Dwight Evans has noticed what Dr. Stanford is doing, he tells ABC News he is ‘very impressed that she took it upon herself to get this done. I needed to help push this to the city's officials. This needs to happen. She deserves the help,” he said.

Until the help comes, it’s Dr. Stanford to the rescue, with a quick tilt of their head, and a five second swab of the nose.

Further proof that in these challenging times, superheroes really don’t need capes, just a mask and a dream.