Who will pay to take care of sick coal miners? The Black Lung Trust Fund is in trouble.

Gary Hairston worked in West Virginia coal mines for more than 27 years.

Like thousands of other coal miners, Hairston was diagnosed with complicated black lung disease, an incurable condition caused by exposure to high levels of coal dust.

He now relies on federal black lung benefits to help pay for his medical care and living expenses. The money comes from a fund that's overextended and running out of money amid concerns that there will be a new increase in cases of black lung disease.

"I was 48 years old when I had to quit work. I couldn't even pay with my grandkids. Then I had to watch my wife go out of the house and start to work to help us make the ends meet at our house. You don't know how that feels," he told a congressional committee on Thursday, adding, "I never did think at a young age that I wouldn't be able to take care of my family."

Hairston now advocates for coal miners through the Black Lung Association.

Recent studies have raised concerns that the number of cases is increasing to the highest levels recorded in 25 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control, especially in miners who worked in West Virginia, Kentucky, Pennsylvania or Virginia.

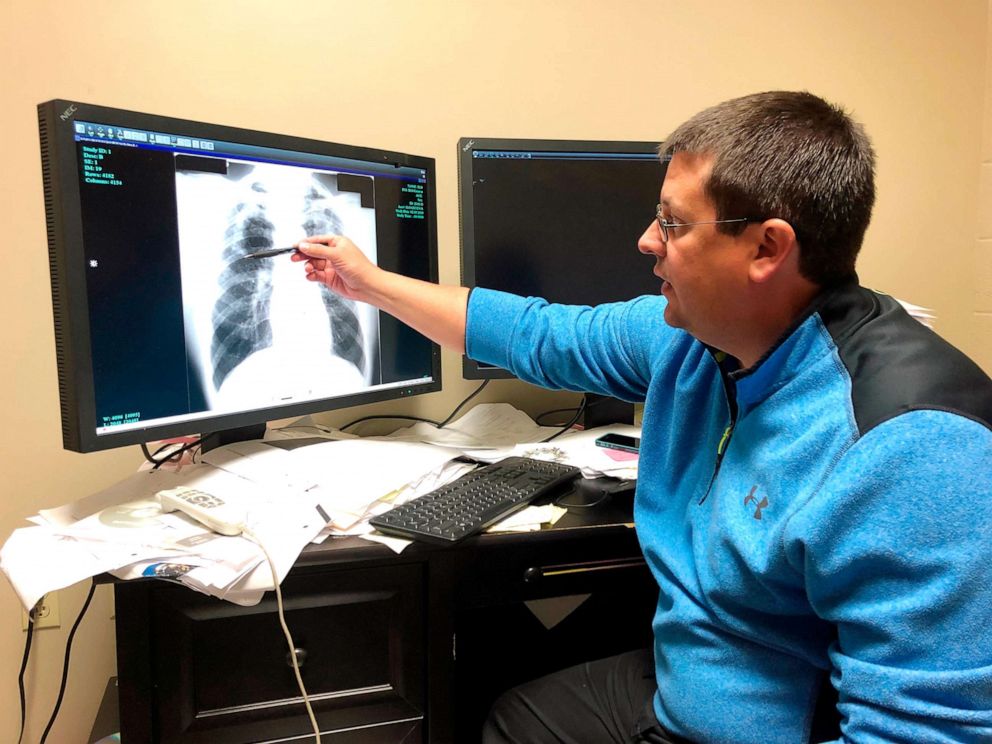

Coal miners are at high risk for developing lung diseases, which can complicate breathing and lead to premature death. The most common form is called black lung disease because the inhaled coal dust and related scarring often appears dark on x-rays.

Coal miners diagnosed with black lung are eligible for federal benefits from the Black Lung Trust Fund, which helps with medical care and expenses if they're no longer able to work.

But the tax on coal companies decreased earlier this year, and Congress didn't renew it. That decline in revenue combined with declining coal production means the trust fund won't be able to cover the costs for 25,600 miners currently enrolled -- or any newly diagnosed with the condition, according to testimony from the Government Accountability Office.

GAO reported the trust fund borrowed $1.3 billion in taxpayer funds in fiscal year 2017, when funding from coal companies ran short, and that if nothing changed it could need more than $15 billion in federal funds by 2050. The office is still conducting work to issue recommendations on how to support the fund.

An additional concern is that miners are exposed to high levels of silica, which can make up a big portion of rocks like quartz that are dug through to reach coal deposits, and which aren't regulated as much as coal dust.

President Donald Trump's administration has taken multiple steps to help the coal industry and bring back jobs they say were under attack under President Barack Obama. But when it comes to coal miners dealing with occupational illness, there's increasing concern that the fund that pays for their medical treatment mines is in trouble, in part because the administration and Congress allowed a tax on coal companies to expire.

A joint investigation from NPR and PBS' Frontline last year reported that regulators weren't preventing cases where miners were exposed to excessive levels of silica.

Rep. Mark Takano, D-Calif., said he could hardly contain his anger at the issue in the hearing.

"Miners would not be dying at these drastic levels if there was effective regulation and strong federal enforcement," he said.

The head of the Mining Safety and Health Administration, which oversees working conditions in mines, told members of Congress the agency has stepped up enforcement and monitoring in mines and is taking steps to set a limit on how much silica miners can be exposed to. Some lawmakers and witnesses at the hearing suggested the evidence about the connection between silica and lung disease was enough for the agency to set an emergency limit, but Assistant Secretary David Zatezalo said he's required to follow a more lengthy administrative procedure.

Zatezalo said the majority of mines are still within the silica limits recommended by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, even though MSHA's limit is technically twice as high, and that new rules have helped decrease exposure to dust even more.

The NPR/Frontline investigation found that about 15% of samples from mines over a 30 year period contained excessive levels of silica.

"Given that the average exposure is already half what OSHA's limit is, it would seem to me that an emergency standard would be uncalled for," he said Thursday.

Cecil Roberts, international president of the largest mine workers union, said Thursday he has testified on this issue multiple times over the years. He called on Congress to set stricter limits for how much silica miners can be exposed to and to take a bigger role in oversight of mine operators.

"We can all come here today and act like we need some more time, but coal miners don't have any time. They're dying in West Virginia, they're dying in Kentucky and they're dying in Virginia, and they don't have any more time to wait here," he told the House Education and Labor Committee in a hearing on Thursday.