Former Patriots football player Aaron Hernandez's fiancee, lawyer on his final notes before his suicide, CTE diagnosis

A new book is revealing chilling new details about the final hours of disgraced NFL star Aaron Hernandez.

Hernandez, once an unstoppable tight end for the New England Patriots, took his own life in 2017 while serving a life sentence for the murder of his friend Odin Lloyd.

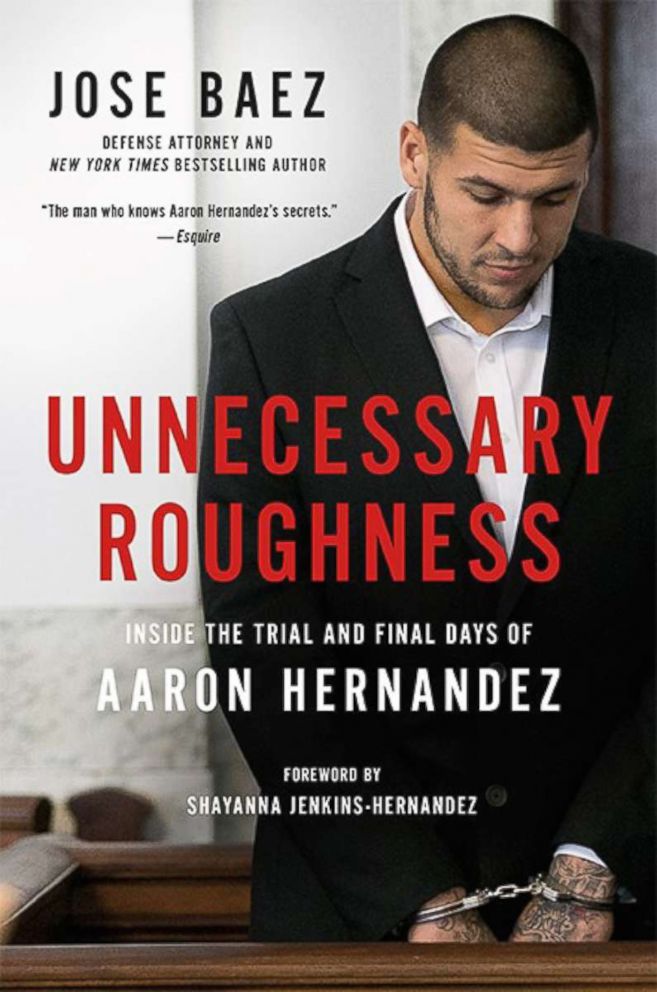

“Unnecessary Roughness,” written by Hernandez’s attorney Jose Baez, includes new information about the night Baez’s client was found hanging in his Massachusetts prison cell from a noose made from a bedsheet.

Hernandez was 27 years old when he killed himself in April 2017.

Before he became a convicted murderer, Hernandez was an All-American at the University of Florida, and was drafted onto the New England Patriots in 2010. Just two years later, he helped Tom Brady and the Patriots make it to the Super Bowl.

After only two years in the NFL, Hernandez signed a five-year, $40 million contract extension with the New England team, including a $12 million signing bonus, the highest ever for a tight end.

But in June 2013, Hernandez was arrested at his 7,000-square-foot North Attleboro, Massachusetts, home for the execution-style killing of his friend Odin Lloyd, who was found shot to death in an industrial lot nearby. He was released from his big contract with the Patriots almost immediately.

After a two-month trial in April 2015, Hernandez was convicted and given a mandatory life sentence. Baez says if Hernandez was alive today, he believes he could have successfully appealed the case.

“Prosecutors have no idea who pulled the trigger and killed Odin Lloyd. So they prosecuted him under what's called a joint-venture theory, which basically means he was with a group of individuals or did, made some decisions to advance that cause,” Baez said.

However, Hernandez’s time in court was not over. After he was arrested for murdering Lloyd, investigators linked Hernandez to another murder: the 2012 drive-by shooting of two men -- Daniel de Abreu and Safiro Furtado -- who had been partying at the same nightclub as Hernandez and his friends.

Hernandez was found not guilty.

“I know beyond any doubt based on what I've seen that Aaron did not commit the two Boston murders. I didn’t represent him in the Odin Lloyd case, but after reviewing the evidence and seeing what I've seen I have a reasonable doubt that he committed that crime,” said Baez.

Baez continued, “I think when you hang around the kind of characters that he was hanging around you ... expose yourself to that type of activity. When your close friend is a drug kingpin who is involved in multiple shootings, you're going to have problems.”

Just five days after his acquittal for the 2012 murders, Hernandez was found dead.

According to Baez, Hernandez wrote three suicide letters -- one to Baez, one to his fiancée, Shayanna Jenkins-Hernandez, and an emotional, yet cryptic, note to his then-4-year-old daughter, Avielle.

“I think anyone who knew Aaron would tell you that the final letters to Shayanna and Avielle ... that’s a different person,” Baez told ABC News’ “Nightline.”

“I think that he didn't know the extent of his sickness,” Jenkins-Hernandez told “Nightline.”

In the letter to Avielle, Hernandez wrote: “I’m entering into the timeless realm in which I can enter into any form at any time because everything that could happen or not happened. I see all at once.”

Jenkins-Hernandez explained what she thought the sentence meant, saying, “What I get from that is that he's telling Avielle that she will have daddy at any time, no matter how she feels at that moment.”

She continued, “It strikes me as not normal. So, something was affecting him at that time where it's kind of more or less like he made his decision, but it just I don't know if he knew what was going on.”

In the letter Hernandez wrote to Jenkins, he refers to her as his “soul mate” and “an angel” and tells her, “I want you to love life and know I’m always with you. I told you what was coming indirectly!”

The letter goes on to say, in part, “This was the supreme almighty's plan, not mine (sic)!” and ending with “NOT MUCH TIME! I’M BEING CALLED! JOHN 3:16”

“The letter he wrote to me was weird. I mean it didn't refer to me as Babe or something more intimate. It was, you know, "Shay," it's very direct, not detailed,” Jenkins-Hernandez said. “There was nothing, I don't know, it kind of leaves me. Not having closure.”

And while the letters to his fiancée and daughter may have seemed somewhat delusional, the note Hernandez allegedly wrote to Baez seemed more like it was written by a man who had plans to live.

“As I read his letter to me, it’s typical Aaron. He starts out with, ‘What’s up brotha (sic)?’ He talks about asking me for a favor to help him reach out to certain artists who helped him through very tough times,” Baez said. “Hip-hop artists and rappers that he wanted to thank for their lyrics, which to me indicates he wants he's looking forward to the future.”

When asked about why Hernandez appeared to write suicide notes to his daughter and fiancée, while writing a letter to Baez that appeared to look toward the future, Baez said, “I think that was the disease taking over. I think that when you have a severe brain disease, logic goes out the window."

Baez believes that years of brain trauma from playing football played a role in Hernandez’s suicide.

“What it tells me is that this is someone with a severe brain injury who is manifesting the symptoms that result from repeated injuries to the head,” said Baez.

After Hernandez’s death, Jenkins-Hernandez donated his brain to Boston University to be studied for signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease that can be caused by repeated head trauma and leads to symptoms such as violent mood swings, depression and other cognitive difficulties.

CTE can be diagnosed only in an autopsy. A 2017 study from researchers at Boston University found evidence of the disease in 110 of 111 former NFL players whose brains were examined.

The NFL responded to an ABC News request for comment with a copy of its fact sheet on player health and safety for the 2018-19 season.

"After a 16 percent increase in concussions during the 2017-18 season, NFL Chief Medical Officer Dr. Allen Sills issued a call-to-action to reduce concussions," the fact sheet said. "The result was the Injury Reduction Plan, a three-pronged approach to drive behavioral changes" that includes more education about concussion prevention during preseason practice, better helmets and rule changes in the league to prevent potentially risky behavior, the fact sheet says.

CTE has been linked with repeated concussions and involves brain damage particularly in the frontal region that controls many functions including judgment, emotion, impulse control, social behavior and memory.

“We've learned that Aaron had the absolute worst CTE, the advanced stages of someone so incredibly young. They had never seen someone with that advanced stage at his at his age,” Baez said.

Jenkins-Hernandez said she saw behavior in Hernandez that would make her think he had injuries to his brain, such as, “the headaches that he encountered, and the memory loss, which I think go hand in hand.”

“I would say there were was a lot of writing down, so a lot of post it notes around that, you know, we had to then so he could remember some things,” Jenkins-Hernandez said of Hernandez’s apparent issues with memory loss.

Dr. Ann McKee, director of the Boston University CTE Center, led the team that studied Hernandez’s brain.

“These are very unusual findings for an individual of this age,” McKee told “Nightline.” “Individuals with CTE and CTE of this severity have difficulty with impulse control, decision-making, a inhibition of impulses or aggression, often emotional volatility, enraged behavior.”

Baez is now suing the NFL on behalf of Aaron Hernandez’s now-five year old daughter, Avielle, asking for compensation because of his extreme CTE that, they say, resulted in his suicide.

The NFL recently filed a motion to dismiss the case.

“What we've learned about CTE is it's not about the concussions,” Baez said. “It’s about the repeated blows to the head. We’re not built to play football.”

For Jenkins, she can’t help but think of the life for her and her daughter that could have been.

“I think that there is a lot of things that he was afraid to personally tell me, things that I could of not necessarily cured, but I could have helped. I could have told [Baez]. I could have, you know, extended my ear out and I just -- it hurts,” she said.