Parents of special needs kids in ‘panic mode’ as virtual learning falls short

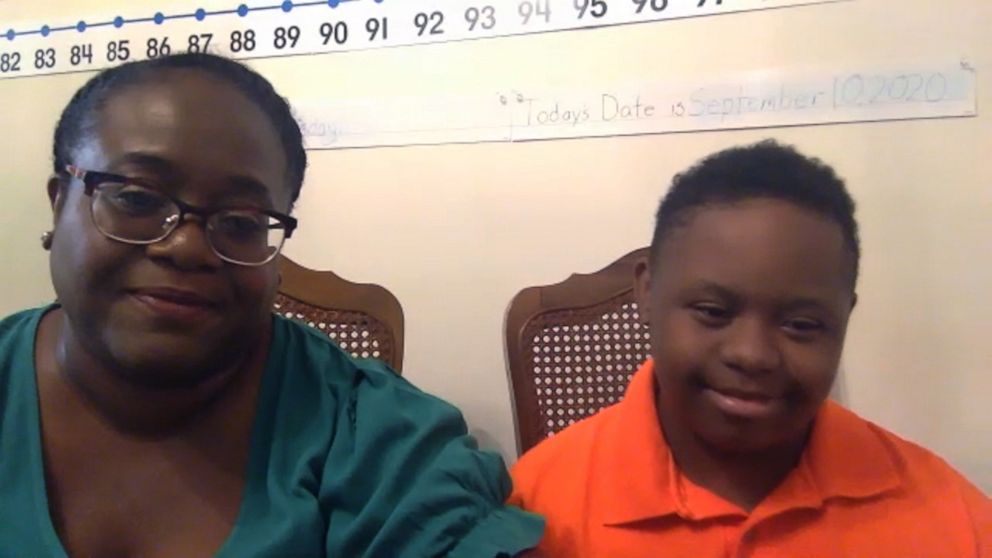

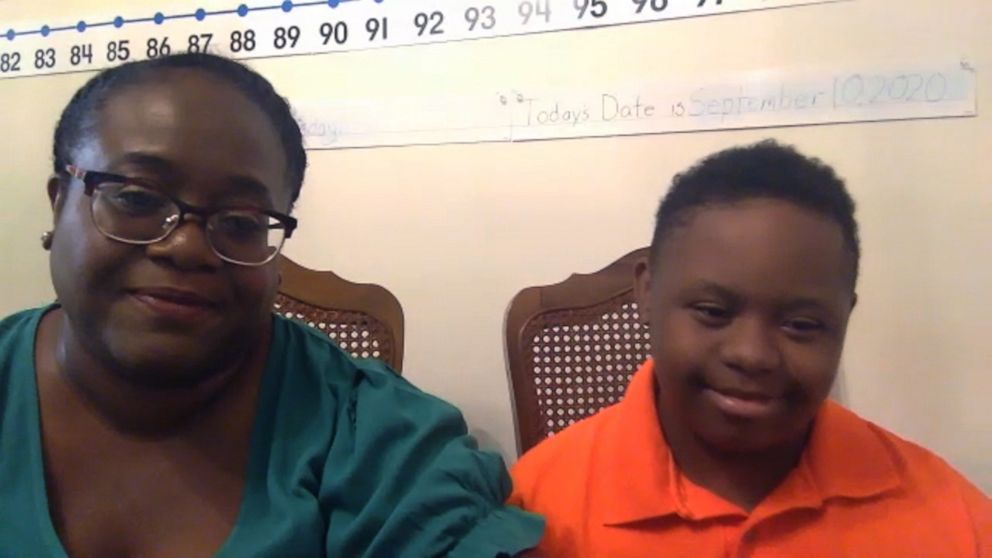

When Opal Foster lost her job during the pandemic, she unexpectedly found herself consumed by another full-time gig that didn't pay: at-home virtual learning supervisor for her son with special needs.

"We're all kind of living in panic mode right now," said Foster, a single mother in Silver Spring, Maryland, who is still unemployed.

Foster spends all day at the family dining room table working with her son, Jeremiah, who has Down syndrome, as he navigates a labyrinth of Zoom classes, counseling sessions and art projects for eighth grade.

"There isn't anybody really available to give you breaks," Foster said. "Financially, I'm not really sure how the end of the year is going to look."

Parenting during a pandemic has meant financial, educational and emotional challenges for millions of Americans, but for those with special needs children it's become a Herculean responsibility.

More than 7 million U.S. public school students receive special education services, according to the Department of Education. With the coronavirus keeping many of those students home, their parents say they have been left to fill the gap.

Stretched thin, many worry their children are at risk of falling behind in their development.

"It has been scary, hectic, making an already challenging existence for someone living with a disability and a family living with a disability even more challenging and limiting," said LeAnn Quinn of Warwick, Rhode Island.

Mother Haley Keisler of Lexington, South Carolina, said the burdens of caring for her two boys could cost her income.

"Because of a nursing shortage, because both boys are virtual school, right now we have to take off work a few days a week occasionally when there's not someone available," she said.

School districts are required by law to develop an individualized education plan, or IEP, for any child with a disability, but many have been falling short of meeting that standard in the pandemic, advocates say.

Virtual learning is simply not an effective option for many children with special needs.

"A lot of parents rely on the additional support they receive in school during the day to help in the development and growth of their children, especially children with special needs," said Misty Heggeness, a U.S. Census Bureau economist who studies families. "There's a likelihood that they will fall behind much more than the average child."

Melissa and Jason Winchell of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, have spent hundreds of dollars of their savings to transform their home into an interactive school for daughter, Moriah, who has Down syndrome.

"It's too overwhelming for her," Melissa Winchell said of Zoom classes. "This is a kid who gets special ed services every minute of her day when she's in school. This remote learning thing is just not working."

The Winchells, who are both teachers, take turns working with Moriah on fifth-grade lessons during the day, then tend to their other students, giving online lectures, virtual counseling sessions and grading papers late into the night.

The couple said they spend one day a week in the kitchen with Moriah, teaching her how to follow instructions and do basic math by baking bread, bagels, pretzels, cookies or cake-pops.

"We're really tired," Winchell said.

Because many kids with disabilities are in high risk groups for COVID-19 infection, social distance and limits on visitors inside the home are essential for many families. Six months into the pandemic, several parents said the social isolation weighed heavily.

"I have been isolated from other adults for a really long time and, you know, my mental health has paid a price for that," said Rob Gorski, a single father of three autistic sons in Akron, Ohio.

Opal Foster said the isolation has led to a "regression" in Jeremiah. "Definitely the social piece has fallen back," she said. "Jeremi used to be much more talkative."

Megan Scully and Chris DeBatt, whose 4-year-old son Danny has a rare brain disorder and is learning to speak using his eyes, said they are trying to celebrate each bit of developmental progress -- even if it's not what it should be.

"I think (Danny's speech) has progressed in a different way than if he were using it sort of organically in a classroom," said Scully, "but his amazing speech therapist Corrine has continued through the pandemic."

Gorski says counterbalancing constant change in routines for his boys is critical to keeping their learning on track.

"It's hard to replicate the structure and the routine and the support that you have in the classroom or in the school building at home," Gorski said. "To find some kind of balance is the hardest part of this."

Masked family hikes in the woods are the new "gym class" for the Gorskis. Science, math and English classes are all online. "It's been a little weird to be honest," said 11-year-old Emmett Gorski. "There are some glitches that need to be worked out."

As for their grade-level progress, Rob Gorski thinks it's inevitable that his kids -- like millions of others -- will fall behind this year.

"We can play catch up on the other side of this," he said, "because the priority is health and wellness."

"Everybody is in the same boat, whether or not you're in the classroom right now wearing a mask and spread apart not being able to interact like normal," Gorski said. "There's nothing we can do at this point but ride it out."