How COVID will make Derek Chauvin's trial in George Floyd's death look like no other

With the arduous task of seating a jury in the middle of a pandemic complete, the first major in-person U.S. criminal trial of the COVID-19 era is set to begin, and medical and legal experts said they expect the prosecution of Derek Chauvin for the death of George Floyd to unfold like no other.

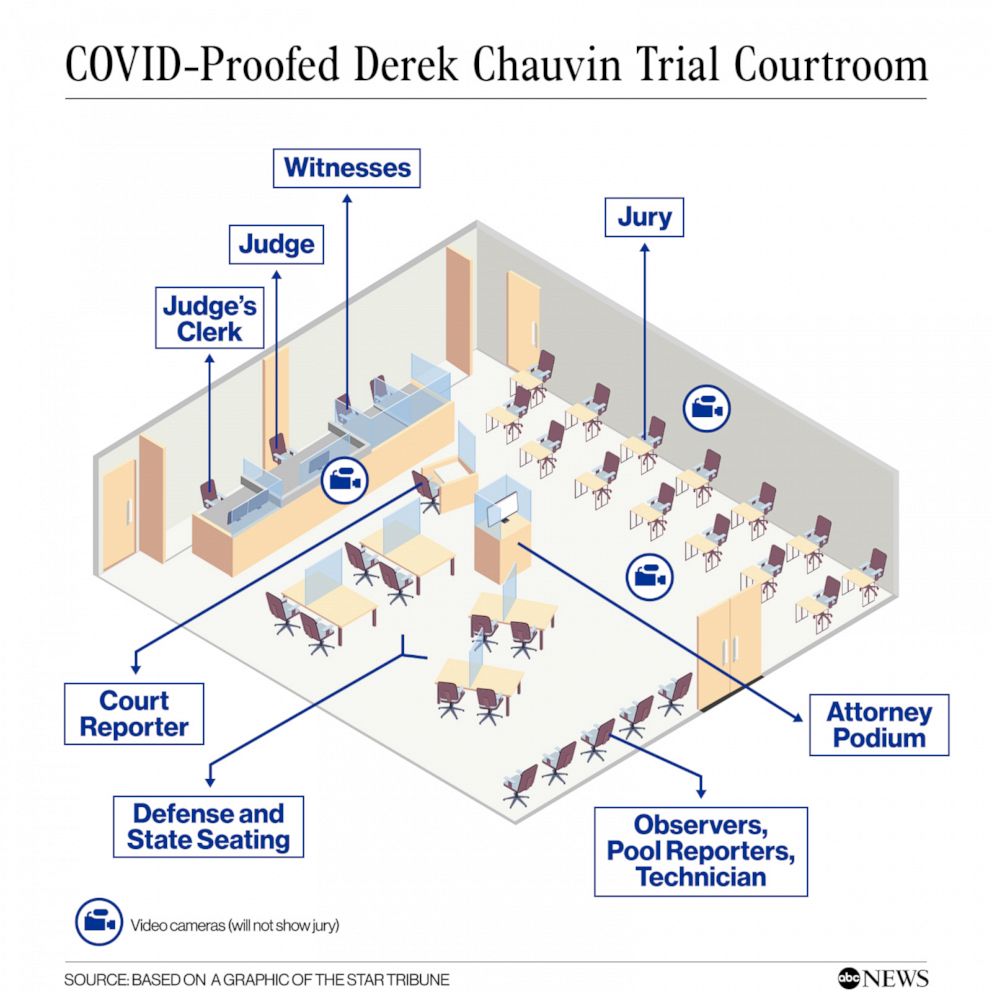

Fraught with both medical risks and judicial pitfalls for the participants, Minnesota court officials have taken extreme measures to keep the contagion from interfering with the pursuit of justice. Attempting to COVID-proof the courtroom, officials have installed plexiglass partitions, ripped out the gallery to accommodate social distancing and are requiring the limited number of people allowed in to mask up.

Everything from the airflow in the courtroom to the placement of hand sanitizer has been painstakingly detailed in a preparedness plan the Minnesota Judicial Branch has developed. Even the judge presiding over the case, 61-year-old Peter Cahill, has felt compelled to tell jurors he has received his first COVID-19 vaccine shot.

The opening statement's in the case are scheduled for Monday.

"It's going to be a case the likes of which none of us have seen before," David Weinstein, a former federal and state prosecutor in Florida, told ABC News. "It's a case that's so important on so many levels to so many people from different segments of society."

Despite the COVID precautions being taken in the windowless 18th-floor courtroom of the Hennepin County Government Center in Minneapolis, Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist and chief innovation officer at Boston Children's Hospital, said the virus can still creep in and wreak havoc.

"It's all about balancing risk and there's no such thing as zero risks, but the steps they have taken with social distancing, barriers and masking clearly would drive risks way down," said Brownstein, a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit. "It's definitely a test case for how one can lead trials in a moment of pandemic."

Pilot program raises concerns

In June, following a three-month COVID-prompted statewide shutdown of the courts, in-person criminal trials began to slowly resume in Hennepin County District Court and others throughout the state under a pilot program. Administered by the Minnesota Judicial Branch, the program requires courtrooms to be certified for trials by adhering to an extensive COVID-19 Preparedness Plan -- a 13-page document providing guidelines on a plethora of precautions from seating jurors 6 feet apart to placing large-screen monitors in front of the panel to view exhibits, rather than handling them.

Safeguards will also alter how private sidebar conferences are usually conducted, having them occur distantly via electronic headsets instead of at the judge's bench, according to the plan.

"We are committed to ensuring courts are doing everything we can to make the criminal jury trial experience safe. As pilots have progressed we have been impressed with the commitment to duty shown by Minnesotans during these turbulent times," Minnesota Supreme Court Chief Justice Lorie S. Gildea said in a statement.

Minnesota State Public Defender Bill Ward told ABC News that for the most part, the pilot program has shown "the sky has not fallen like, frankly, we all thought it was going to be, about a year ago."

"The biggest concern I had, and I would say most lawyers would have, was working with citizens who were afraid of being seated as jurors," Ward added. "If they felt that their safety was at risk due to a lack of spacing, or due to a lack of protection or cleaning of the areas, then they would not feel safe being on a jury."

During the 11-day jury selection phase in the Chauvin case, potential jurors were interviewed individually about their worries over the virus. After seeing measures taken in the courtroom, most said their concerns were eased by the reconfiguration of the courtroom to protect them.

"You can't be too careful," a prospective juror said.

Ward said early results of the pilot program justified potential jurors' fears.

"We've had cases where people had symptoms after the trials had begun, where the cases were declared mistrials and had to start over again," Ward said.

The first case tried in Hennepin Country under the pilot program had to be put on pause when the judge was forced to go in quarantine after being exposed to a staff member who tested positive for the virus, the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported.

Ward, among the stakeholders who consulted on the courts' COVID-19 Preparedness Plan, said the fear factor still exists despite all the precautions.

"What we try to do as lawyers is have the jurors only focus on the case," Ward said, "but the minute somebody coughs or sneezes, are they worried that they're going to contract the disease? That became very concerning."

Because of COVID restrictions on access to the courtroom, Cahill has allowed the Chauvin trial to be televised gavel to gavel, which would be the first such time in state history.

"The cameras are set up in a way that people can see and have the transparency of what's happening," Ward said. "But I think the real test cases are the ones where people aren't watching. Those are the ones we have to be most concerned about to make sure my clients are being treated fairly and their families are being treated fairly as well."

The case will be live-streamed, but it will not show jurors in order to protect their anonymity.

Ward said his office has filed petitions asking the Judicial Branch to prevent counties that don't have courtrooms large enough to accommodate social distancing from using churches as courtrooms.

"We fought against that pretty vociferously because of the idea of the separation of church and state and, of course, the backgrounds of the jurors and of the accused," Ward said.

COVID's impact on Chauvin trial so far

Chauvin is facing charges of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter stemming from Floyd's death on May 25, 2020. He has pleaded not guilty.

Because of concerns over COVID, Cahill ordered that Chauvin be tried separately from his three co-defendants, former Minneapolis police officers J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao. They're charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder and manslaughter and are scheduled to go on trial in August. They all have pleaded not guilty.

The prosecution's key evidence in the case against all four men is a bystander video of the attempted arrest of Floyd. Chauvin, who's white, is seen kneeling on the back of Floyd's neck for a prolonged amount of time as the handcuffed and prone Black man repeatedly cried out, "I can't breathe" before going unconscious. Floyd, 46, initially was accused of trying to use a counterfeit $20 bill to buy cigarettes. He later died at a hospital.

"It is an advantage to the other defendants in this case and a disadvantage to the government," Weinstein explained, "because now there's less likely to be guilt by association because they're not sitting at the same table. And the other co-defendants are now given a preview of what the government's case is going to look like."

And if the jury doesn't convict Chauvin, Weinstein added, "well then how in the world is the government going to proceed? How do you proceed against people you're charging with aiding and abetting?"

Because of COVID restrictions, only one member at a time from Floyd's and Chauvin's families will be allowed to sit in the courtroom, and two media representatives will be permitted in to compile pool reports for reporters outside.

Fifteen jurors have been picked for the panel, including three alternates. Initially, the judge and lawyers had agreed to have just two alternates, but on Friday Cahill decided to add an additional alternate juror to ensure there are enough jurors to begin the trial.

Cahill said one of the alternates will likely be dismissed on Monday as long as the others show up.

Given the continuing COVID-19 crisis, Weinstein questioned whether moving forward with just two alternates will be enough to get through a long trial.

"What if during the trial a juror comes down with coronavirus? With only two alternates that might or might not allow you to keep going," Weinstein said. "So now you're going to have to stop the trial for two weeks. You're going to have to put the brakes on, put everybody into quarantine. If that happens again, how many times is the judge going to be willing to let this case stop and start, stop and start, stop and start?"

Impact of masked witnesses and jurors

As the trial commences, Weinstein said other COVID-related issues are sure to arise, including whether witnesses be allowed to keep their face masks on while testifying.

During jury selection, Cahill allowed potential jurors to remove their masks while seated next to him in the witness box with a plexiglass partition between them. Cahill has not said whether witnesses will be allowed to keep their masks on.

"A lot of what happens in a trial is not just the answer, but rather what's telegraphed when you're giving the answer or when you're asking the question," Weinstein said. "So if the judge is going to have these proceedings take place where a witness is going to wear a mask, then you're going to lose out on a lot of the way a person's face changes when he or she answers a question."

Weinstein said that such a scenario could create an appellate issue on a confrontation clause by the defense, or at least objections along the lines of, 'Your honor, we object to the mask because it doesn't allow my client to confront, through me, the witness.'"

He said Chauvin's attorney, Eric Nelson, might even raise the issue in his closing argument.

"If I'm a defense attorney, I'm going to play that, 'Oh, everybody else took off their mask. This witness didn't. Don't read anything into it ladies and gentlemen, but did you see how they reacted. What did they have to hide?'"

Ward, the Minnesota public defender, said the issue has come up in the pilot trials.

"I actually have a PowerPoint I could show you on different facial expressions that are hidden by masks," Ward said. "It is a concern. The lawyers have made the arguments to allow the witness to lower their masks."

Weinstein said both the prosecution and defense lawyers will be hamstrung when it comes to reading the faces of masked jurors spaced 6 feet apart to glean an indication of how they're reacting to a witness or a specific piece of evidence.

During the trial, attorneys have been ordered to stand at a podium with a plexiglass shield attached, restricting lawyers from moving around as they speak.

One of the most significant effects COVID will likely have on the trial is whether it will put a crimp on the camaraderie of the jury, especially during deliberations, Weinstein said.

"A traditional jury is packed into a jury box, 12 people, two to four alternates, all right on top of each other, all becoming one large family unit as the case progresses. How is that going to occur in a pandemic when you're going to need to keep people socially distant from each other?" Weinstein said. "That's going to play into the deliberations, that's going to play into how they're going to interact with each other, how willing they will be to listen to somebody else's opinion."