What does it mean to 'pack' the Supreme Court? Has it been done before?

Democratic nominee Joe Biden and running mate Sen. Kamala Harris have faced growing pressure from Republicans to say whether they'd try to 'pack' the Supreme Court if Democrats were to win the White House and control of Congress in November, after both candidates have repeatedly dodged questions on the issue.

"You will know my opinion on court-packing when the election is over," Biden has said. "The moment I answer that question, the headline in every one of your papers will be about that rather than focussing on what's happening now. This election has begun. There's never been a court appointment once the election has begun."

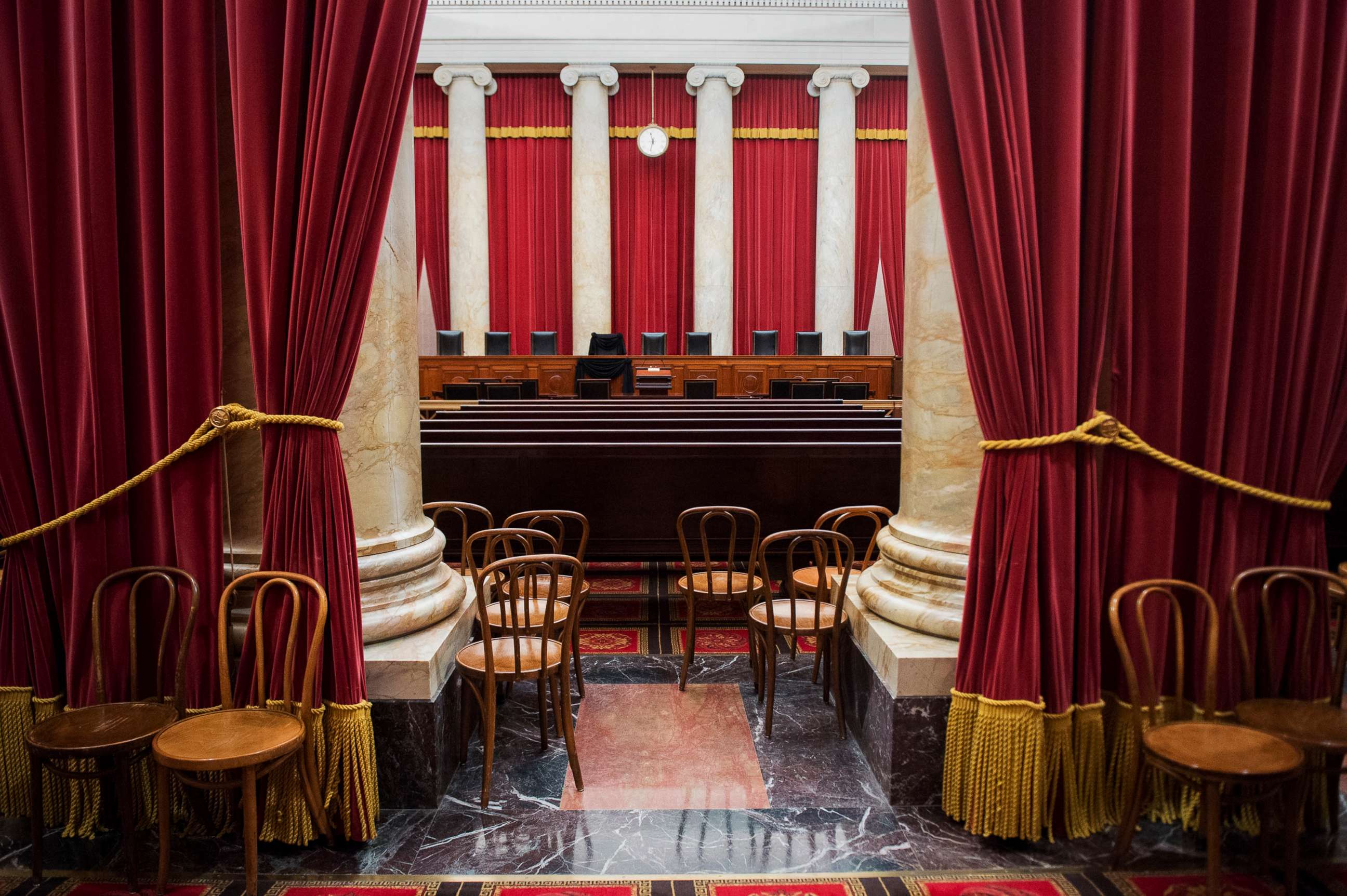

The idea of adding more justices -- or what critics call "packing" the court to secure a desired majority -- is not unprecedented but has taken on new life with the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Senate confirmation hearing for Judge Amy Coney Barrett.

Some Democrats -- including Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer -- and progressive groups have threatened to try to add justices to counter the effort by President Donald Trump and Senate Republicans to get Barrett confirmed before Election Day.

So, can a party in power really "pack" the court?

Yes, in theory. The Constitution does not set the number of justices on the Court. Congress can change the number by passing an act that is then signed by the president -- and the number of justices has changed in American history.

George Washington nominated the original six justices on Sept. 24, 1789, after Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789 establishing a Supreme Court. For the next eighty years, the number of seats shifted in order to give the ruling party more power.

In 1801, President John Adams and a Federalist Congress reduced the Court to five Justices in an attempt to limit any nominations available to incoming President Thomas Jefferson.

Once in power, Jefferson and his Democratic-Republicans soon repealed that act, restoring the Court to six Justices and later adding a seventh.

At one point, the number grew to 10 under President Abraham Lincoln, in an attempt to uphold Union war policies. In 1866, with a Congress at political war with President Andrew Johnson, it cut the size of the court to seven justices and barred Johnson from naming any new justices.

After President Ulysses S. Grant was elected in 1868, Congress set the number at nine, where it has stayed ever since.

If Democrats seize control of the White House and Congress, in 2021 Schumer could present legislation to add justices, the Democratic-controlled Congress could pass it, and a President Biden could sign it into law.

But no past effort to pack the court has ever proven successful.

The most famous example is when Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1937 announced a controversial plan to expand the Supreme Court to as many as 15 justices after the court struck down parts of his New Deal legislation.

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, commonly referred to as the "court-packing plan," faced steep opposition even from within Roosevelt's party. His own vice president and Senate majority leader rejected it, and a vote was never taken in Congress.

It was a massive political defeat for the popular president in what many deemed a power grab.

Experts say public opinion -- not legal process -- remains the hurdle for adding justices.

"If they [Democrats] controlled both houses of Congress, it could pass just like an absolutely normal law, no different from a, really, farm appropriations bill. The main barrier to that would be public opposition," said Judge Glock, senior policy adviser for The Cicero Institute, told NPR last month.

In the past, Biden has said he opposed expanding the court, saying it would politicize the judicial branch.

"I would not get into court packing. We had three justices. Next time around, we lose control, they add three justices. We begin to lose any credibility the court has at all," he said at a debate last year.

He also told "Iowa Starting Line" on the campaign trail last July, "No, I'm not prepared to go on and try to pack the court, because we'll live to rue that day."

But that was before Justice Ginsburg's death so close to a hotly-contested election.

ABC News' Devin Dwyer contributed to this report.