OPINION: History shows us why the fight for LGBTQ equality is far from over

Queer Americans live in schizophrenic times. Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act protects LGBTQ employees from discrimination, finally extending federal workplace protections to the more than half of U.S. states that had resisted them. The week before, on the fourth anniversary of the Pulse nightclub shooting, the Trump administration announced a rule change rolling back healthcare protections for trans and gender-queer Americans by redefining sex as determined by “biology,” or birth gender, effectively allowing religious liberty advocates in medical facilities “of faith” to discriminate against the most vulnerable subgroup of the LGBTQ alliance.

Gay conservative columnist Andrew Sullivan, in the wake of the court decision, asked hypothetically whether now might be a good time for the gay rights movement to declare victory, having assimilated gay and lesbians into a society where they’ve supposedly ceased to be minorities. Religious conservatives would encourage such complacency, as they mean to fracture the LGBTQ alliance and then quash it through religious-based discrimination. United, we stand. Divided, we fall.

They will make trans and gender-queer citizens the test case in private hospitals, locker rooms and bathrooms – opportunistic locations, where exposed bodies can become the objects of ideological interrogation. There, trans and gender-queer students and patients now oddly lack the same protections as the average LGBTQ employee. And it would be naïve for gays and lesbians to think that such interrogations will end with their bodies.

My concerns are rooted not in suspicion, but in history. Forty-seven years ago today, on the night of June 24, 1973, fire struck a working-class gay bar called the Up Stairs Lounge on the ragged edge of New Orleans’ French Quarter. Intentionally set, it was the deadliest fire on record in city history and the worst mass killing of homosexuals in 20th-century America, claiming 32 lives and injuring 15 others. Yet, few Americans were willing to acknowledge such a catastrophe because a gay victim was then considered to be marginal and criminal. Seven out of 10 of Americans, when polled, considered homosexuality to be “always wrong.”

“They viewed homosexuality… as something heterosexuals did that was bad,” remembered Rev. Troy Perry, the legendary gay activist and minister.

The public response to the tragedy reflected those prejudices. As I wrote in my book Tinderbox, a nonfiction account of the Up Stairs Lounge disaster, the police investigation closed without answers or an outcry, and the chief suspect was never questioned. The body of one victim, a gay religious minister named Rev. Bill Larson, was left hanging out a street-facing window as a public spectacle for four hours. City leaders failed to address or even acknowledge the tragedy and the pain it wrought. Local churches refused to bury the dead, and jokes that circulated after the blaze spoke of “flaming queens” who should be discarded in “fruit jars.” Bodies that went unclaimed were dropped into unmarked graves in a potter’s field and lost.

The Up Stairs Lounge once stood on the edge of gender, racial and religious mores. It served as a forerunner to modern queer spaces in that it was racially integrated, permitting Black and white gay courtship, as well as a haven for trans patrons, then self-identifying as “cross-dressers” in an era when gender dysphoria was not well understood. Local members of a radical, gay-affirming Christian congregation called the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) found safe harbor at the Up Stairs Lounge, and their flock held Sunday services in the bar’s theater hall for several months. The Up Stairs Lounge even hosted receptions for MCC “holy union” ceremonies, or spiritual conjugations for same-sex couples. Patrons of the Lounge had an anthemic song they liked to sing together around the bar’s white baby grand piano, which summed up their ethos: “United We Stand,” by the Brotherhood of Man.

“It was just a wide variety of people,” recalled Up Stairs Lounge survivor Ricky Everett in an interview for Tinderbox. “We had politicians who come in there. We had doctors, lawyers, everyday hourly-wage blue-collar people.”

Fire survivors like Everett, in their trauma, could not fathom how their society conspired to squash an awakening and push them back into hiding. So profound was the denial and minimization of this event that it took into the next century for the Up Stairs Lounge to be known and memorialized, with the names of the victims spoken aloud. Yet today, burial places of several fire victims are unknown, and more than several Up Stairs Lounge survivors choose not to share their sexualities with employers and healthcare providers. Now in their 70s and 80s, these men and women braved an inferno, survived AIDS and grew old only to fear Medicaid discrimination and conceal their orientations to those who provide their insurance. As queer elders, they view their economic livelihoods as indelibly tied to the healthcare system, and they don't want to take risks. They, like trans folk and many others in the LGBTQ crusade, face a “closet at the end of the rainbow,” and it shows that the advancement of queer Americans has been uneven.

How can this be? How can cisgender gays and lesbians of the American middle class assimilate while the rest of the LGBTQ alliance sits in a waiting room for equality? How can 34% of LGBTQ elders fear that they will have to hide their identity to access suitable housing and 40% of homeless youth happen to be queer in the same nation that Pete Buttigieg, a gay mayor, runs for president? Because the opposition targets those they perceive as vulnerable to attack. Currently, they see a prime path through bigotry by pitting gender identity against birth gender.

Gender minorities have been the target of opportunity for religious conservatives since same-sex marriage became federally mandated in 2015. As “sexual orientation” evolved into a protected class, religious conservatives doubled down on the precept that God determines sex at conception, and they’ve fought it into elementary schools and doctor’s offices. This goes way beyond who bakes a cake for whom. Trans youth are at higher suicide risk; nearly 25% of trans people do not seek healthcare they need for fear of mistreatment; more than 80% of the victims of fatal anti-trans violence since 2013 have been trans women of color.

“We are the most afraid we’ve ever been, but we’re also stronger than we’ve ever been,” Mariah Moore, program associate for the Transgender Law Center, told The New York Times last year.

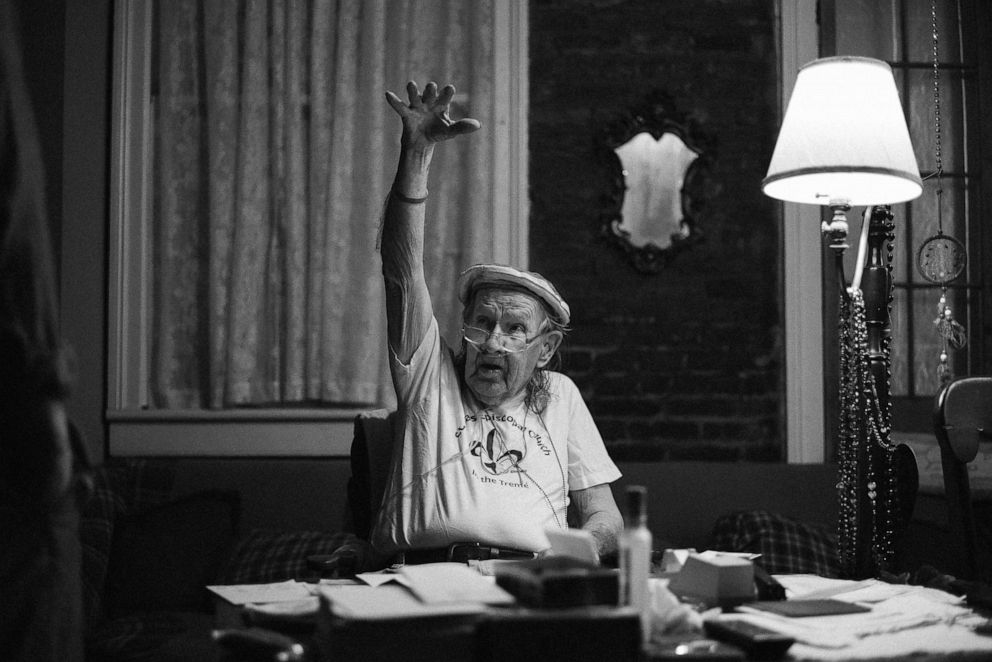

Up Stairs Lounge survivor Stewart Butler, who descended the front staircase to the bar with seconds to spare, witnessed disparities such as these in the aftermath of the fire, wherein straights and closeted elites worked to smother a working-class gay consciousness – even if such repression meant denying the dead their dignity. He channeled his grief into becoming a self-described “political animal,” a queer activist who worked more than a decade to secure anti-discrimination protections for homosexuals in New Orleans, which finally passed in 1991.

But Butler did not declare victory for himself. Instead, he recruited a local protégé in trans activist Courtney Sharp, who had been pushed out of her job at an engineering firm because of her trans status. Working together, Sharp and Butler campaigned to extend anti-discrimination protections in New Orleans to transgender residents, and they succeeded in 1998. That same year, in a decade when many in the LGB alliance resisted adding “T” to the acronym, Sharp and Butler pushed PFLAG, a national advocacy group encompassing more than 400 regional chapters, to incorporate transgender issues. Through their efforts, PFLAG became the first national queer rights organization in America to add transgender people to its mission statement.

“It amazed me that Stewart, a cisgender gay man who had no skin in the game, would take up our cause,” recalled Sharp.

Butler passed away this March at the age of 89. The “political animal” never got to witness a U.S. Supreme Court decision that affirmed employment protections for all LGBTQ Americans.

“I thought of him all day long,” said Sharp. “It’s amazing, after all the resistance to us having common cause in the 1990s, to see trans and gay issues affirmed side by side.”

Sharp is currently counseling the family of a transgender youth who attempted suicide and cannot get access to New Orleans schools. Her work continues. As does the work of others who fight against a return to the place where we queer citizens began: denial and erasure.

Robert W. Fieseler is the author of “Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation.”