Officials seek thousands of poll workers ahead of Election Day, fear shortage due to COVID-19

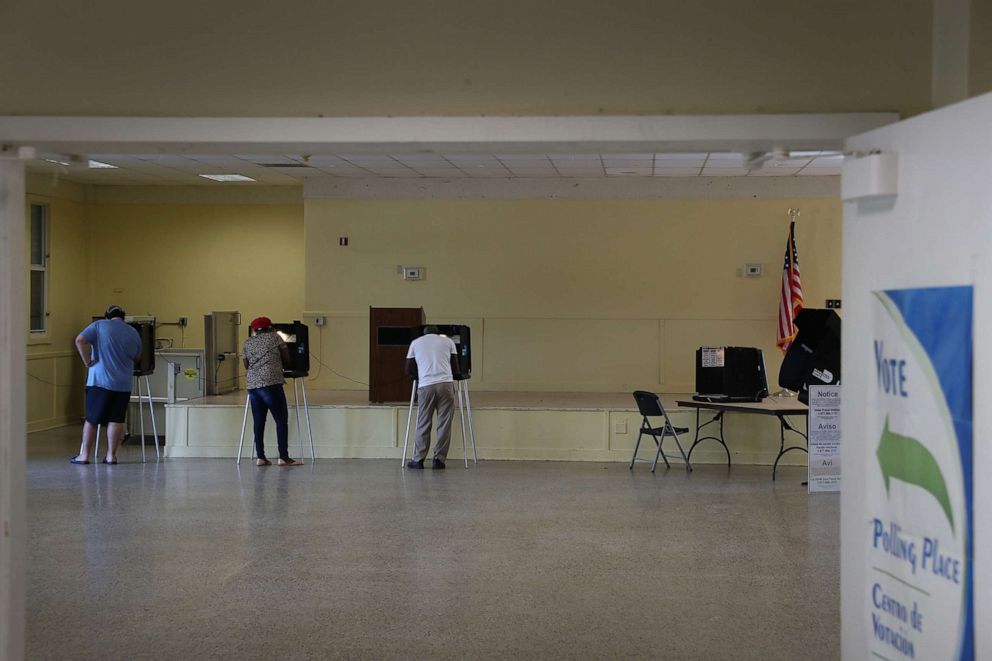

With two months to Election Day, state and local officials are scrambling to sign up poll workers, with experts warning a shortage of volunteers could inject even more uncertainty into a season already plagued with challenges from the coronavirus pandemic.

Officials in several key battleground states told ABC News they are still short thousands of poll workers and could be forced to reduce the number of polling locations -- a move that would likely bring longer lines to in-person voting sites.

"Everyone is working really, really hard to find poll workers right now," said Myrna Perez, the director of the Brennan Center's Voting Rights and Elections Program. "It's a challenge that we are facing as a country, but it is a challenge that folks are trying really hard to meet."

From checking in voters to collecting and tabulating ballots, election workers across the country handle "the nuts and bolts of what we need to do to make our season run," Perez told ABC News. For years, volunteers have skewed older. But this year, many are staying home because of COVID-19. In response, the local and state authorities who organize elections have been looking for younger volunteers.

Some officials are getting creative. In Kentucky, state officials needing to fill 15,000 posts convinced the Guild of Brewers to advertise election worker jobs on beer cans.

In Ohio, the state is offering attorneys continuing education credits if they volunteer. And the secretary of state launched a "Styling For Democracy" initiative with barbershops and hair salons, to register patrons to vote and, hopefully, sign them up to be poll workers.

According to Secretary of State Frank LaRose's office, Ohio currently has 33,500 poll worker commitments -- several thousand short of the 37,057 needed at minimum for the election, and more than 20,000 short of the state's 55,588 goal.

"The thing that we're thinking about more than anything right now is poll worker recruitment," LaRose said on NBC's "Meet the Press" Sunday.

A range of volunteers are also trying to help. Max Weiss, a law student at William and Mary University, whose grandmother served as a poll worker, started an organization to connect law school students with local election officials in every state to help with processing absentee ballots.

"Trying to prepare people ahead of time to get this counting done as quickly as possible is probably a primary goal for us," Weiss said.

A broader effort led by basketball superstar LeBron James is working with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund to recruit young poll workers in Black communities in swing states.

"Our community needs poll workers on Election Day," James tweeted out last week to his 47 million followers. He included a link to the organization "Power the Polls" where volunteers can sign up.

Election workers are typically paid for the days they work, and some companies are telling employees they can take paid time off to volunteer this fall.

Roughly 1 million poll workers were needed to run the 2016 presidential election, according to a report by the Election Assistance Commission, which also found that more than half of workers were over 60 years old. That same survey found 65% of polling locations reported it was "very difficult" or "somewhat difficult" to recruit an adequate number of workers four years ago.

Coronavirus has made recruitment "an even bigger concern," Wendy Underhill, the director of elections and redistricting for the National Conference of State Legislatures, told ABC News.

Nearly one quarter of counties across eight battleground states are potentially in urgent need of poll workers ahead of the 2020 election, according to a new analysis by Carnegie Mellon University researchers. Rayid Ghani, a professor there, helped create the new tool, which uses historical data to analyze what counties may have the greatest need to help focus recruitment efforts -- but with constantly changing circumstances, it is difficult to predict.

"The biggest uncertainty is going to be how many people can be shifted to vote by mail, and how many people are left to vote in person," Ghani explained. "Given that we're trying to shift people to vote by mail as much as possible, then the question becomes: Which counties and which precincts are still going to have that gap?"

Officials are hoping to learn from challenges the nation faced during the primaries this spring and summer, when some voters waited for hours to cast ballots -- as they did in Milwaukee after the city downsized the number of polling sites from 180 to five because of staffing shortages. Gov. Tony Evers eventually mobilized 700 members of the Wisconsin National Guard to staff polling sites in 40 counties in the state's August party primary.

In many states, the challenges won't end on Election Day. Volunteers are also needed to rapidly process results, particularly in states where counting of absentee ballots cannot begin until Election Day. Without more workers counting, the results could take days to be tabulated, Underhill said.

Those rules are in effect in Wisconsin and Michigan, two major swing states, as well as in New York, where it took six weeks for workers to process absentee ballots to get the final results of the recent Democratic congressional primary.

While many officials remain optimistic they will eventually have enough election workers to avoid a repeat of challenges during the presidential primaries, interest in volunteering is uneven.

In Florida, election officials in Hillsborough County and Pinellas County told ABC News they have seen more interest this year from potential volunteers. But in Pennsylvania, "there are still plenty of jurisdictions that are still struggling to find poll workers," Lisa Schaefer, the executive director of the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania, told ABC News.

Additionally, several state election officials contacted by ABC News did not have a sense of how many workers were needed statewide. They either referred ABC News to local jurisdictions, or said they had not surveyed their counties yet. This uncertainty has resulted in an incomplete picture of the needs of many states.

Experts also said they are seeing counties try to recruit more alternate poll workers than usual to account for unexpected no-shows.

"Counties are definitely making a bigger push to hire even more backups, just in case an individual that was supposed to come in is exposed to COVID, maybe has COVID or is nervous of exposure," Eryn Hurley, an associate legislative director at the National Association of Counties, told ABC News.