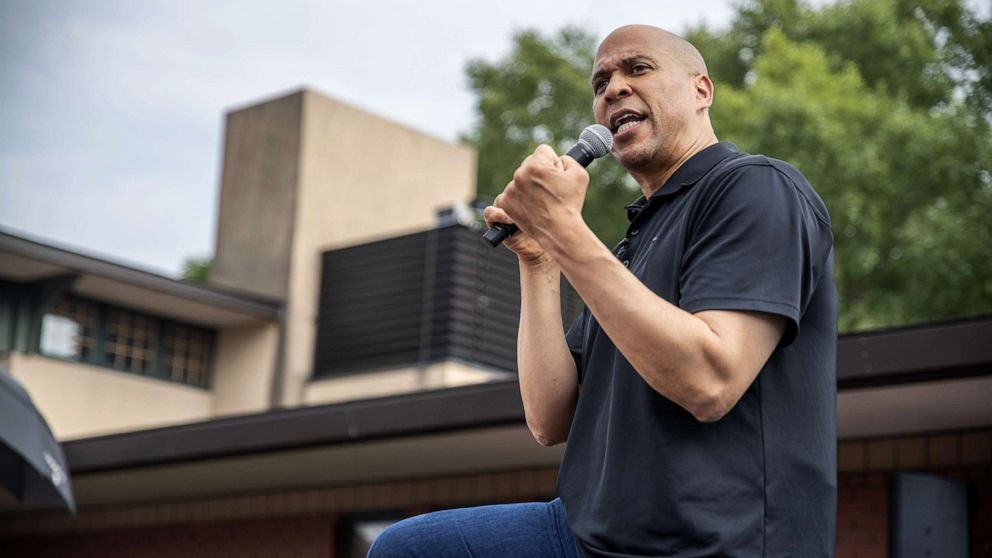

For Cory Booker, water crisis awakens ghosts of past Newark water scandal

As a presidential candidate, Cory Booker has made environmental protections a central tenet of his social justice platform. As a United States senator, he emerged as a leading voice on the front lines of safe water for urban-dwellers.

But a growing water quality crisis gripping Newark, New Jersey, is bringing fresh attention and scrutiny of Booker's own record when he was that city's mayor -- at a time when the water system was marred by scandal.

The two crises may be separated by time, but as images spread of Newark officials handing out bottled water to residents grappling with dangerous water pollution, ongoing water problems could prove increasingly uncomfortable for his 2020 presidential campaign.

"This is something that he will have to answer for," said Krista Jenkins, a professor of political science at Fairleigh Dickinson University. "As with anyone who is a chief executive of a large city, everything that happened under his or her watch is going to become fodder for any of his or her rivals."

In a tweet on Wednesday, Booker called on the federal government to step in.

"Everyone deserves clean, safe water," Booker wrote. "It's shameful that our national crisis of lead-contaminated water disproportionately hits poor black and brown communities like my own."

The latest figures from federal observers show that children in Newark's Essex County are in fact nearly four times more likely to have elevated blood lead levels than those in Flint, where cost-cutting measures resulted in lead and other toxins seeping into the drinking water supply. As a result, city officials handed out filters more than eight months ago. Following recent tests that showed elevated levels of lead in the drinking water of two houses using the filters, the EPA recommended Friday that local officials in Newark distribute bottled water to residents.

In a speech in New York City on Monday, Booker initially sought to address the water crisis in Newark but he did so obliquely, lamenting it as an example of "environmental injustice" without mentioning the city's name.

The Watershed scandal

Those who have followed the issue of drinking water quality in Newark say the subject dredges up uncomfortable memories of the years Booker served as mayor, from 2006 to 2013.

Until 2013, the job of keeping water safe belonged to a quasi-public agency called the Newark Watershed Conservation and Development Corporation. It fell under the purview of the mayor, who appointed board members and who sat as chair.

In 2014, the New Jersey state comptroller published an investigation into the agency's stewardship of the city's infrastructure that was highly critical of Booker's administration. The investigative report "found that from 2008 through 2011, the [watershed] recklessly and improperly spent millions of dollars of public funds with little to no oversight by either its Board of Trustees or the City" – both of which, at the time, were led by Booker.

The state comptroller's report referred several cases to law enforcement. Federal prosecutors brought charges against eight people involved in the watershed scheme. Six of them pleaded guilty and five of them received lengthy prison sentences.

One of them, Linda Watkins Brashear, the watershed's executive director from 2007 to 2013, was sentenced in 2017 to more than eight years in prison for accepting nearly $1 million in kickback payments for awarding no-show contracts.

Booker had appointed her to the post.

All told, federal prosecutors uncovered how members of the watershed board and employees at the agency brazenly siphoned millions of dollars from the company over the course of several years.

Was Booker on the hook?

While Booker was never personally implicated in the scheme, the state comptroller report cited several missteps on Booker's part that led to conditions ripe for scandal.

As the ex officio chairman of the board, Booker never attended a meeting, according to the state comptroller's office. And while Booker's predecessors commonly named proxies to attend board meetings on their behalf, the state comptroller found that Booker failed to designate a replacement.

"When we asked the then-mayor about the lack of board members, he said that he had difficulty moving board nominees through the [City] Council," the state comptroller's office wrote. "We note, however, that the mayor held the seat ex officio and thus did not need the advice and consent of the council to designate an alternate for himself."

In a separate civil suit filed by trustees of the watershed in 2015, plaintiffs named Booker as one of more than two dozen parties responsible for the scandal. But U.S. Judge Vincent Papalia dismissed Booker from the suit in June of 2016, citing a statute that protected him from prosecution because he served on the board only in his capacity as a public servant.

The scandal's fallout

Among those who have worked in and closely observed Newark's city government, there is disagreement about whether the residual fallout from the watershed scandal contributed to the city's recent issue with elevated lead levels.

A longtime director of the city's water treatment facility argued that the watershed scandal remained isolated to corporate mismanagement and did not affect the city's water operations.

"The watershed corporation was only responsible for the operations, not engineering," according to Andrew Pappachen, who formerly served as director of the Department of Public Works in Newark. "Mismanagement of the financials, that was the scandal … the operation of the watershed and the engineering were separate [from each other]."

A Booker campaign spokesperson on Wednesday sought to distance the watershed scandal from Newark's elevated lead levels.

"There is just no connection between the people who defrauded Newark residents at the Newark Watershed a decade ago and the very real water crisis impacting Newark residents today -- other than they both share one word in common - 'water,'" according to Sabrina Singh, a campaign spokeswoman.

But Dan O'Flaherty, a Columbia University economics professor and former Newark city employee, penned an independent report in 2011 asserting that fallout from the watershed scandal would have lasting implications for the city's water infrastructure.

"Some people have made a lot of money, but the water and sewer systems still appear to be in bad shape, at least according to the people who run them," O'Flaherty wrote. "Enormous resources have been siphoned into schemes that would benefit those insiders even more, while problems with water and sewer infrastructure continue."

In light of Newark's latest water scare, O'Flaherty told ABC News that he believes the watershed scandal contributed to mismanagement at the agency that has led to the city's current predicament.

"The human capital of the water department was not renewed and deteriorated -- they weren't hiring engineers," O'Flaherty said of Booker's tenure atop the agency. "So you have a seriously depleted department in 2013, and that was a department which made a mistake in the subsequent years."

That mistake occurred in 2015, after Booker was no longer mayor, when city officials decided to adjust water treatment chemistry in an effort to comply with new EPA regulations. Municipal officials lowered pH levels in the city's water treatment facility, with the intended consequence of diminishing cancer-causing chemicals in the water supply, according to several people familiar with the problem.

Erik Olson, senior director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, whose nonprofit has sued the city of Newark over alleged violations to federal law resulting in elevated lead levels, criticized that decision.

"To really address the problem you have to change how you treat the water in a more comprehensive way, and it looks like they were looking for a shortcut -- and the long-term consequence is elevated lead levels, it appears," Olson said.

He described the current water crisis in Newark as a culmination of several factors. Although he did not have detailed knowledge about the watershed scandal, he agreed with O'Flaherty that "you've got to have competent engineering staff running a large water treatment plant.

"If you don't, it's a formula for trouble," Olson continued. "Right now all those chickens are coming home to roost in Newark."