Navy honors its 1st female jet pilot with historic all-female flyover during funeral

The Navy conducted its first-ever, all-female flyover on Saturday to honor the the life and legacy of retired Navy Capt. Rosemary Bryant Mariner, the service's first female jet pilot.

Rosemary passed away at the age of 65 on Jan. 24 following a five-year battle with ovarian cancer. The Navy's tribute, referred to as the "missing man formation," took place during her funeral service in Maynardville, Tennessee.

The flyover, which included female aviators from squadrons based at Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia, featured four F/A-18E/F "Super Hornets" flying in formation.

The largest-ever formation -- 21 aircraft -- was used in December for the funeral of President George H. W. Bush, also a Naval aviator.

A career of "firsts" as a female Naval aviator

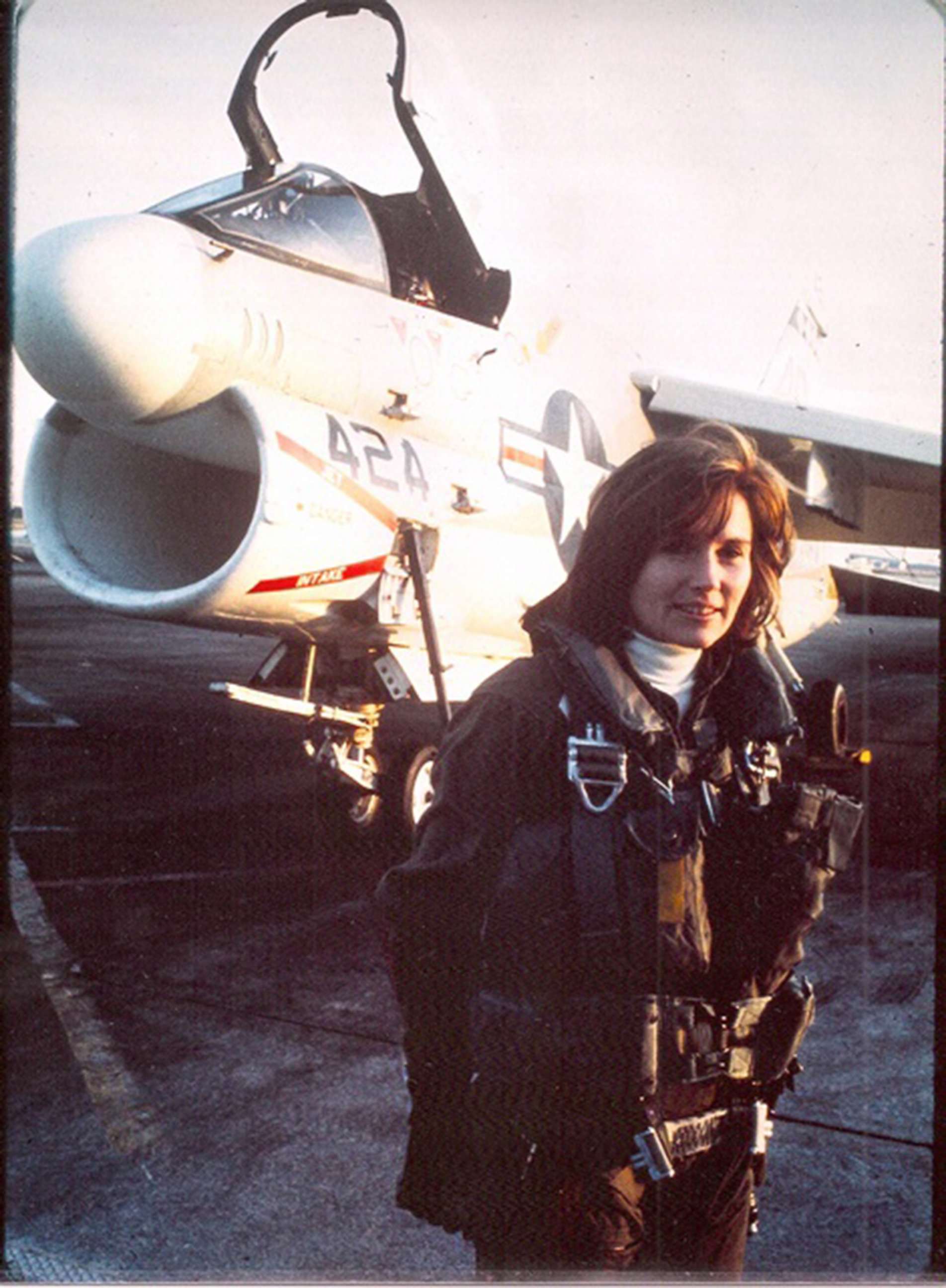

In 1973, Rosemary Mariner, then Rosemary Conatser, was one of eight women selected to fly military aircraft and received her "wings" from the Navy the following year. She became the service's first female jet pilot, according to her obituary.

It would be one of many firsts for the young aviator.

In 1982, she became one of the first females to serve aboard a U.S. Navy warship, the USS Lexington, where she also qualified as a surface warfare officer. Then, eight years later, she became the first woman to command a military aviation squadron.

Mariner went on to attend the National War College to earn a masters in national security strategy. Her last assignment in the Navy would be at that same college serving as the chairman of the Joint Chief's Chair in Military Strategy there.

She retired from the Navy in 1997 as a captain. According to Naval Air Forces Atlantic, she had logged 17 aircraft carrier landings and completed over 3,500 flight hours in 15 different aircraft.

It was perhaps an unsurprising path for Mariner, who was born on an Air Force base in Harlingen, Texas. Her father, Capt. Cecil James Bryant, served in the Army Air Corps during World War II and later in the Air Force during the Korean War as an attack pilot. He was killed in a crash in 1956 when Rosemary was just three years old.

Her mother, Constance Boylan Bryant, was a Navy nurse during World War II and later a nurse anesthetist in San Diego, where Mariner grew up.

According to her husband and fellow Naval aviator Tommy Mariner, she began flying planes when she was just 15, using money saved from washing aircraft. Two years later, she became the first female at Purdue University's aeronautics degree program and flew for the small Purdue airlines before earning her instructor and commercial ratings before she turned 20.

She had hoped to pursue a career as a commercial airline pilot, but the field was still closed to women in 1972. It wasn't until Mariner read an article about the Navy opening its flight training to women that she decided to graduate early and attend the Navy's Women's Officer Candidate School.

"An aircraft gun is a great equalizer"

Beyond her remarkable accomplishments and "firsts" as a woman in the Navy, Mariner will be remembered for how she forged the way for other women in the military and pushed the boundaries of social change.

During her career, she served on working groups advising various Navy offices about female aviators, including challenges with sizing uniforms and equipment, according to her husband. She also advised military service academics on their admission and integration of women.

"Rosemary recognized the need to push for full integration of women in Naval Aviation," her husband said. "She felt without full integration in the air, the Navy would continue to experience institutional and individual discrimination that would lead to continued problems."

In the early 1990s, Mariner served as president of the Women Military Aviators and -- while still in uniform -- organized female service members to lobby Congress to repeal the combat exclusion clauses and remove legal and policy restrictions on women in the military.

Her efforts proved fruitful and, in 1993, Defense Secretary Les Aspin opened the majority of aviation assignments to women, including the ability for women to fly combat missions.

According to her husband, Mariner would often say of women serving in combat: "An aircraft gun is a great equalizer."

"Throughout her career, Captain Mariner was both willing to serve as a mentor to others and was deeply grateful to the men and women who enabled her to pursue her dreams," her obituary reads.

In retirement, Mariner served as a resident scholar at the Center for the Study of War and Society at the University of Tennessee where she taught military history. She was also an adviser on national defense policy and women's integration into the military for the U.S. Navy and various media organizations, including ABC News.

"A voracious reader and an eager academic, she devoted herself to a love of knowledge," her obituary said. "In recent years, this included the disease which took her life, which she sought to understand as fully as possible. As expected, she tenaciously fought an implacable foe to the end."

In addition to her husband, Mariner is survived by her daughter, Emmalee, who attends Duke University.