Nature-based or lab leak? Unraveling the debate over the origins of COVID-19

An accidental lab leak, or the dark side of mother nature?

That fundamental question -- about the origins of a COVID-19 pandemic that has taken nearly 4 million lives -- has sparked a political firestorm in the U.S. and threatened the already fraught ties between Washington and Beijing.

So far, multiple investigations have yielded few definitive conclusions. And as infection rates and deaths tail off in many developed countries, the Chinese government's perceived lack of cooperation into those investigations has prompted some of the world's leading virologists to reconsider the possibility that this pandemic could have been caused by a lab accident.

In the early days of the pandemic, experts largely felt that the most likely explanation was that the virus jumped directly from animals to humans -- like all other pandemics and epidemics have in the past. Attention turned to a closely quartered wet-market in the central Chinese hub of Wuhan, freshly scrutinized for the exotic wild fare, which offered ample opportunity for an intermediary host. But while environmental samples from the market came back positive for the virus, animal samples that were tested ultimately did not.

Conservative political leaders in the U.S. have long seized on an alternative explanation for the virus' spread, some insinuating that the virus could have been engineered as a weapon at a famous coronavirus research center in Wuhan.

With no proof available, accomplished scientists and public health officials stand on both sides of the debate. But all parties agree on the stakes: Uncovering the truth could help prevent the next global pandemic.

Now, at the behest of President Joe Biden, the U.S. intelligence community is scrambling to deliver answers, prompted by the depth of the potential evidence still untapped -- and despite concerns that the answers may never be found.

Tune into Nightline on Monday, June 14, for an ABC News investigation into the origins of the novel coronavirus.

Key clues, a decade in the making

To understand more about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, experts look back nearly a decade -- to an abandoned copper mine in southwestern China. In 2012, a team of miners cleaning out bat excrement fell ill with respiratory illnesses. Three ultimately died.

Researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology flocked to the site, where they "sampled the viruses that were found in those bat droppings in those caves, and brought them back to their lab," explained David Feith, a former State Department official who helped investigate the origins of COVID-19.

One of the viruses that researchers retrieved from the mines and brought back to their lab in Wuhan is about 96% similar almost identical to SARS-COV-2 -- a point that advocates of the lab-leak theory have highlighted as crucial evidence.

Virologists say that 96% similar virus is a cousin -- not a twin -- of SARS-CoV-2. But its existence reveals that scientists at Wuhan Institute of Virology could have been within striking distance of discovering the virus that ultimately caused the pandemic.

"Of all the places in the world where there could be a natural outbreak from transmission, from an intermediary host in the wild, what are the chances that that would ... happen in Wuhan, the town with the only level-4 virology institute in all of China?" said Jamie Metzl, an adviser to the World Health Organization and former national security official in the Clinton administration.

The Chinese government and leaders at the Wuhan Institute of Virology have vehemently denied that the virus came from their lab.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian responded to the rekindled interest in investigating the lab-leak theory in late May, accusing the Biden administration of playing politics and shirking its own responsibility, and saying Biden's order showed that the U.S. "does not care about facts and truth, nor is it interested in serious scientific origin tracing."

Metzl and other lab-leak theory advocates have pushed for further investigation, and the need to determine whether Wuhan scientists working on the coronaviruses may have inadvertently contracted the disease and spread it to the community.

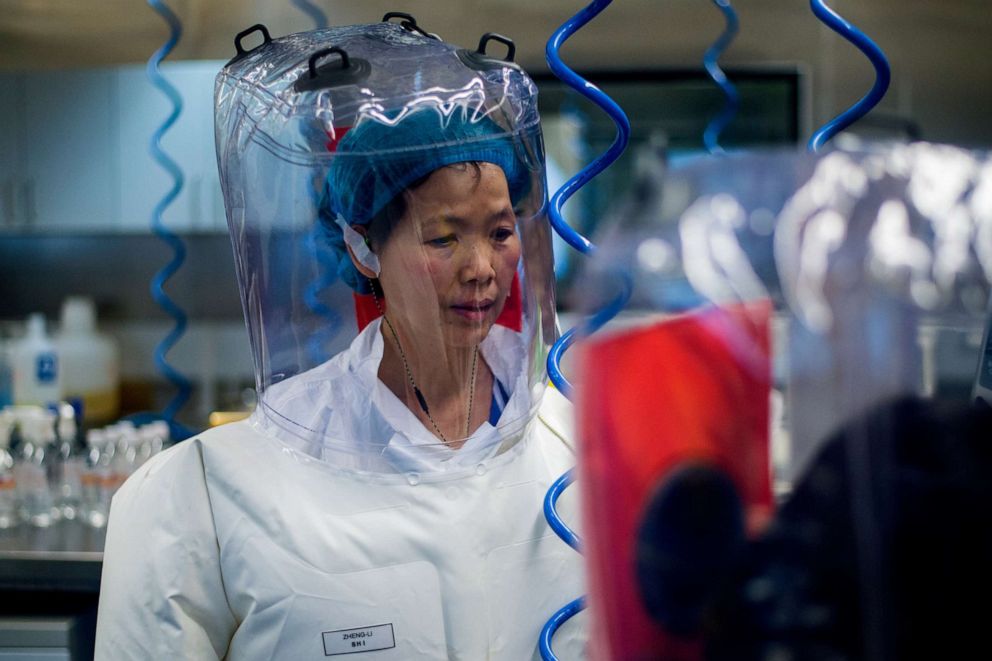

The possibility of such a leak was a distinct possibility, even to Shi Zhengli, a lead researcher in the Wuhan facility who is colloquially known as "Bat Woman" because of her decades-long research of coronaviruses. Shi told Scientific American last year that when the COVID19 virus first emerged in Wuhan, she remembered wondering, "Could they have come from our lab?"

After testing the novel coronavirus' viral genomes, Shi said her team determined that they did not match any samples from the lab, and dismissed the premise.

"That really took a load off my mind," Shi told Scientific American. "I had not slept a wink for days."

Scientific consensus or dangerous groupthink?

Despite some fringe skepticism -- often emanating from voices with a long record of criticizing China -- the idea that COVID-19 jumped from animal to human somewhere in nature became the overwhelming consensus. Political voices in favor of the lab-leak theory, particularly from President Donald Trump, served to polarize the issue further and largely pushed the scientific community away from a willingness to consider the lab-leak theory.

Early in the pandemic, the then-president and his allies sought to shift blame for the poor U.S. response toward China -- seeking to re-brand the coronavirus as the "China Virus" or the "Kung Flu." With Trump weaponizing accusations of a lab leak, even some within his administration recognized it could undermine solid evidence supporting that theory.

"There was so little space, even for Democrats, even for progressives, to ask the questions," said Metzl.

In February 2020, a group of 27 prominent scientists penned a forceful letter in The Lancet condemning any "conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin."

Several leading virologists argued that if the disease had been explicitly engineered in a lab, there would be evidence of that in its genomic sequence. But because there is no such evidence, "the weight of probability would very, very, very strongly indicate that this was a natural event," said Dennis Carroll, chairman of the Global Virome Project and a signatory of The Lancet letter.

A World Health Organization-led team that visited Wuhan in January of this year released their long-awaited findings in March, echoing a similar stance: A lab leak was "extremely unlikely," the report said, and determined that animal-to-human transmission through an intermediary host remained a more plausible explanation. But ultimately, the team ruled nothing out.

"Most likely the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is going to be linked to this large wildlife trade," said Robert Garry, a virologist at Tulane University. "And we know that there are many farms and other sources of these animals that are trapped in the wild and brought to big cities like Wuhan and then distributed to other places."

In fact, newly published data shows just how often wildlife is bought and sold in China, with researchers recently documenting the trafficking of 38 wildlife species and more than 40,000 individual animals in Wuhan's markets from May 2017 to November 2019.

But as Garry readily concedes, scientists haven't yet found that animal host -- a gap in the narrative that has emboldened some lab-leak theorists. Researchers still have yet to identify an animal source, which Garry said "could take years."

Further complicating matters: The director of the Chinese CDC has also said that samples taken from animals at the wet-market tested negative for the virus, meaning finding the natural host could prove more elusive than initially expected.

The void of definitive evidence has prompted calls among some, including former high-ranking members of the Trump administration, to question the virus' natural origins -- and to continue investigating.

"Everybody got into this groupthink," said Metzl, "and that was the story."

New evidence supporting lab-leak theory?

Among the circumstantial evidence that could support the lab-leak theory, some researchers have pointed to the fact that the Wuhan Institute of Virology has in the past conducted a controversial type of scientific research called gain-of-function.

"They were doing what some people have called gain-of-function research -- seeing how the world's scariest viruses might infect human cells," Metzl said.

Gain-of-function research is a technique used by scientists to enhance aspects of an organism. It is common in some fields as a means to study genetic variations and better understand biological entities -- but its use in certain settings to enhance the lethality or transmissibility of a virus has become controversial.

"The idea was, 'Let's understand these viruses so we know what we're facing,'" Metzl said. "The counterargument was, we're playing with fire. If it turns out that COVID-19 stems from an accidental lab incident from the Wuhan Institute of Virology or the Wuhan CDC, it will turn out that that fear was certainly well-founded."

The fear that researchers' work within the lab could be tied to the pandemic was bolstered in April 2020 when the Washington Post reported that U.S. embassy officials who visited the Wuhan Institute of Virology in recent years sent two cables back to Washington about "inadequate safety at the lab" tied to its gain-of-function research on bat coronaviruses.

Then, in January 2021, a State Department report revealed that several Wuhan Institute of Virology researchers fell ill in the fall of 2019 with "symptoms consistent with both COVID-19 and common seasonal illnesses" -- though it's not clear if they had COVID-19, the flu, or possibly another illness. ABC News confirmed from a separate U.S. intelligence report that three researchers sought hospital treatment in November of 2019.

Shi Zhengli insists that she tested all her workers for COVID-19 antibodies, and all tests came back negative.

David Asher, a former U.S. official who led the State Department's probe into the coronavirus' origins, said China's refusal to allow access to American investigators suggests it had something to hide.

"We're talking lights out. There was no cooperation and there still is no cooperation," Asher said. "So the cover-up could be worse than the crime if the crime wasn't really suspiciously horrible."

ABC News also reported in June 2020 that satellite images showed dramatic spikes in auto traffic around major hospitals in Wuhan in the fall of 2019, suggesting the novel coronavirus may have been present before the outbreak was first reported to the world.

Meanwhile, ABC News reached out to all 27 of the scientists who penned the February 2020 letter "denouncing conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin." Of the 12 who replied, one now believes a lab leak is more likely and five more said a lab leak should not be ignored as a possibility. Four others stood by their stance in the letter, and another called for a complete and thorough investigation.

Dr. Charles Calisher, a Colorado State University virologist and the lone signatory to completely change his position, told ABC News that he now believes that "there is too much coincidence" to ignore the lab-leak theory and that "it is more likely that it came out of that lab."

In addition to the circumstantial evidence pointing to a possible lab leak, allegations that the Chinese government has not been transparent has weighed on the minds of those seeking to examine all possible explanations.

Marion Koopmans, a Dutch virologist who traveled with the WHO to Wuhan for their investigation, said the Chinese government cooperated to an extent, but said "it was not so easy" to gather information.

"Was everything you would wish to see on the table? No," she said.

For U.S. government investigators, "interest spiked considerably in March of 2020 because we were dealing with the very concerning problems of the Chinese government's cover-up of what was happening in Wuhan," said Feith, the former State Department official under President Trump.

"We were concerned that they were not accepting U.S. offers of help that would have involved U.S. scientists and other international scientists getting in on the ground to be able to learn things," Feith said. "We were concerned that the information that the Chinese authorities were giving to the outside world through the press and through the World Health Organization was unreliable-- and might have been deliberately misleading."

After the WHO released its March report casting doubt on the lab-leak theory, the organization's chief, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said gaps in their probe merited further investigation, and that the team had "expressed the difficulties they encountered in accessing raw data."

"I do not believe that this assessment was extensive enough," Ghebreyesus said. "Further data and studies will be needed to reach more robust conclusions."

"As I have said," he added, "all hypotheses remain on the table."

"It's important to stay open-minded, because we don't know exactly what happened," said Koopmans. "We are scratching the surface -- and it's important that we learn and collaborate to learn from these outbreaks."