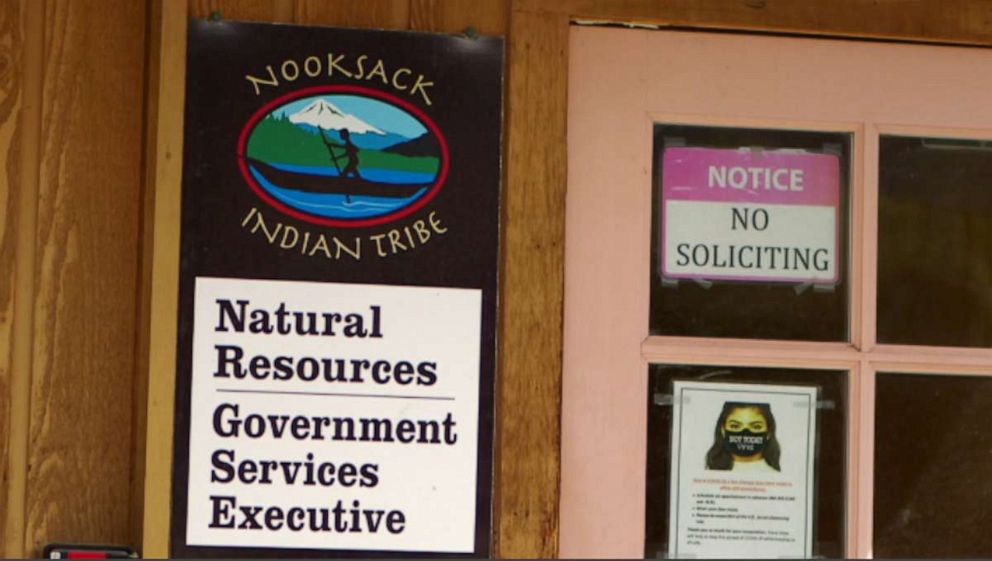

Native Americans facing disenrollment fight to remain with tribes

Hearing stories and learning about the Nooksack Indian Tribe has been a part of Santana Rabang’s life since she was a young child, growing up in Deming, Washington, near the banks of the Nooksack River.

She says her identity as a Native American was passed down from generations who were a part of the Nooksack community.

“I was raised in this community my whole life since birth. I've known that I am Nooksack. I was raised in Nooksack. That was instilled in me,” Rabang told ABC News.

“That ancestral knowledge that's passed down generation and generation. It's not that plastic tribal I.D. that states I'm Nooksack. It's the fact that my great grandmother told me I'm Nooksack.”

Rabang was still a teenager when she and 300 other members of the Rabang family were disenrolled from Nooksack in 2016. The move to disenroll had started years earlier when a former tribal chair questioned the Rabang’s ancestral lineage to the tribe.

The "Nooksack 306", referring to the members and families being disenrolled, were “incorrectly” enrolled in the 1980s, according to former chairman Ross Cline Sr. The tribe claims the people being disenrolled have no lineage to Nooksack.

Now, Santana and many others are still fighting to preserve their family history and their lives on the reservation.

“We're going to fight as long as we can,” Santana said. “If it gets to the point where they're going to come here and physically remove us, then that's the point that we'll get to. But we're not going to go anywhere.

As part of the disenrollment process, over 60 people who self-identify as Nooksack, but who have been disenrolled, are facing eviction from their homes.

The U.N. weighed in, expressing concerns over the evictee’s human rights and due process and urging the U.S. government to step in and “halt” the evictions.

“We appeal to the U.S. government to respect the right to adequate housing … and to ensure that it abides by its international obligations, including with respect to the rights of Indigenous peoples,” experts from the U.N.’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights said in a Feb. 3 statement.

The Nooksack Tribe issued a statement shortly after demanding an “immediate retraction” of the U.N.'s press release, claiming it as “false” and referencing an investigation “which never took place.”

The federal government also responded to the U.N. , issuing a statement claiming the Nooksack Indian Housing Authority had complied with the rental agreements and its own procedures within the eviction process.

“We also recognize the detrimental effects that evictions can have on a community, particularly on the Tenants and their families," the department stated in a press release. "Though they lack tribal citizenship, they are members of the community, and we encourage the Tribe to treat them with dignity and respect their legal rights moving forward.”

The Nooksack Tribe is one of the 573 federally recognized tribes that operate as sovereign nations. With approximately 2,000 enrolled tribal members, the federal government has little power to meddle in internal affairs like disenrollment.

The Rabangs were hopeful that the newly elected Nooksack Tribal Chair, Rosemary LaClair, might look more favorably on their case and evaluate their documents “with open eyes.”

However, LaClair supports the disenrollment of the Rabangs.

“I need to defend the Nooksack people," LaClair told ABC News. "I need to defend my children and portray the truth that Nooksack, we're humble people and there's not much that we have to be offering even our own people. The little resources that we do have, we need to make sure is secured for our future."

“It's not a war between families because it's the simple fact that they do not have lineage to Nooksack.”

But Michelle Roberts, who's also a part of the Rabang family, thinks a war between families is exactly what this disenrollment is about. Roberts thinks the Rabangs are being targeted because of how large their family is, and the fact that other members of the tribe did not want the Rabangs to have positions on the tribal council.

Now Roberts, who formerly served on Nooksack’s tribal council before her disenrollment in 2016, is being evicted from her home.

She’s been living in her house for almost 15 years, and has been fighting her eviction in tribal court. The final ruling, however, could take months.

“They want to use [disenrollment] as a tool to remove our family,” Roberts told ABC News. “Native Americans are known for oral history, and when your grandparents say, ‘You're from a certain area, this is who you are, this is where you belong,’ you believe them. And having to find documents to prove that it's kind of demeaning."

For Rabang, she said the most hurtful part of the process is the feeling of being stripped of her identity.

“It's a direct attack on who I am, and my identity is who I am, how I was raised, my culture is who I am. When they try and take that away, it pushed me down a journey of questioning myself for a second,” Rabang told ABC News.

Rabang now lives in Lummi, the tribe where her mother is from. While she found refuge within the Lummi tribe, she’s not considered a member either because she doesn’t meet the tribe’s blood quantum requirements there.

Blood quantum was imposed by the U.S. government in the early 1900s as a means to define and limit citizenship within Indian tribes. Nooksack also uses this method to measure the amount of tribal blood in a person’s ancestry when enrolling new members.

Santana has been advocating against the use of blood quantum to determine someone’s lineage.

“Blood quantum isn't how we identify as indigenous,” Santana said. “It's not the amount of blood that I have in me. It's the fact that it's there and lives through me is all that matters to me, but I'm not enrolled anywhere.”

Robert Rabang, Santana’s grandfather, is also facing eviction from the house he owns. He told ABC News that he’s fighting to stay to preserve his mother’s legacy who was a part of the Nooksack Tribe.

“It's been really stressful,” he said. “It just hurts. All these people were our friends when we first came up here, now they're all turning their backs like, you know, it's really difficult."

“I didn't want to give up my mom's fight. I'm fighting for her. It could get really ugly because I'm not leaving here.”

LaClair said the disenrolled members have no rights over their current homes since they are owned by the Nooksack Tribe. With limited space, she said they are pushing people like Robert and Michelle to leave so there could be space for some 60 members who are on the waitlist for housing.

LaClair said she’s even had to convert one of the homes on the reservation into a homeless shelter.

“Our resources are for Nooksack tribal members. If we allow them to stay, we would be in conflict with our agreement with HUD. And being in conflict knowingly, we could lose our sources for all Nooksack tribal members,” LaClair said.

“We're not saying that they don't belong anywhere else. We encourage them to find their lineage to where they do belong.”

LaClair believes it’s now time to move past the scrutiny of disenrollment the tribe has faced, so they can focus on providing resources for current and future members.

“Disenrollment did happen in 2016. It was a while ago and we're past it. They've had since 2016 to look for other housing,” LaClair said.

As chairwoman, LaClair wants to focus on economic development for the tribe to ensure there are enough jobs for its members. She also plans to invest in a cemetery, develop more housing options for tribal members and implement initiatives to protect the tribe’s natural resources, which heavily depends on salmon fishing.

LaClair also said enrollment of new members has been increasing. Over the past decade, LaClair said the tribe enrolled 300 new members with lineage to Nooksack.

During her first general council meeting in April, LaClair said they approved 20 new enrollment applications.

While it’s been nearly a decade since the Rabangs have been affected by disenrollment, Santana said she will continue to fight as long as it’s necessary to defend her family history and her own identity.

“Speaking out on this not only helps me within my healing journey, but I know it also helps open the door to provide a safe space for other people who question themselves, questioning their identity. We are who we are because of how we were raised and nobody can take that away from us,” Santana said.