What happens if Mueller decides to subpoena President Trump?

Picture this: Special Counsel Robert Mueller and his agents sitting face to face with President Donald Trump, questioning the commander-in-chief before a grand jury that could determine the fate of both the ongoing probe of Russian interference in the 2016 election and, with it, the Trump presidency.

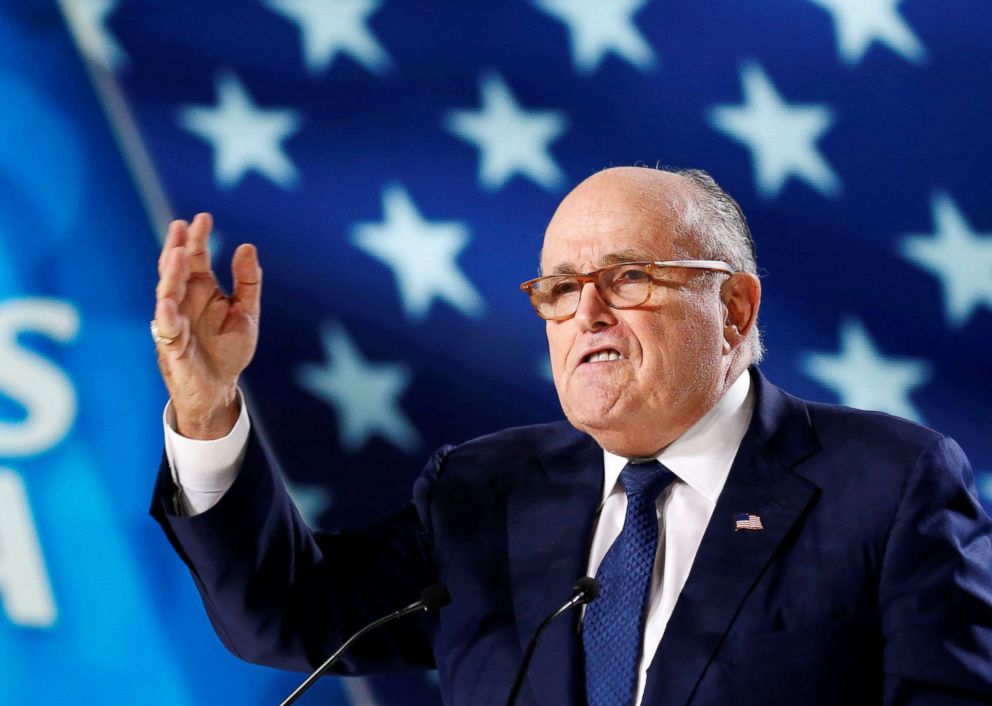

Could it happen? For the past several months, the president’s personal lawyers, Rudy Giuliani and Jay Sekulow, have been publicly chronicling their version of back-and-forth negotiations over a voluntary interview with the Office of the Special Counsel. After teasing a number of supposed deadlines for a decision, they have most recently suggested that the outcome will be known by September 1, though even that date seems elastic.

If Trump refuses to submit to an interview, Mueller will be faced with a momentous decision of whether to seek to compel President Trump to testify.

If Mueller should choose to issue a subpoena, the ensuing power struggle could represent an inflection point in the Special Counsel’s investigation.

Attorneys for President Trump contend they would contest a subpoena all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. Such a move would push the country into unchartered territory and lead to a potential constitutional showdown between the executive and judicial branches of government

“A subpoena for live testimony has never been tested in court as to the president of the United States,” Sekulow said earlier this month on ABC’s This Week with George Stephanopoulos.

There have been similar confrontations in recent history, but each stopped short of settling the fundamental question of whether a sitting president can be required to testify before a grand jury in a criminal investigation.

“There are cases that have come close,” said Alex Whiting, a Harvard Law School professor and former federal prosecutor. “But there’s been no case that directly resolves that point.”

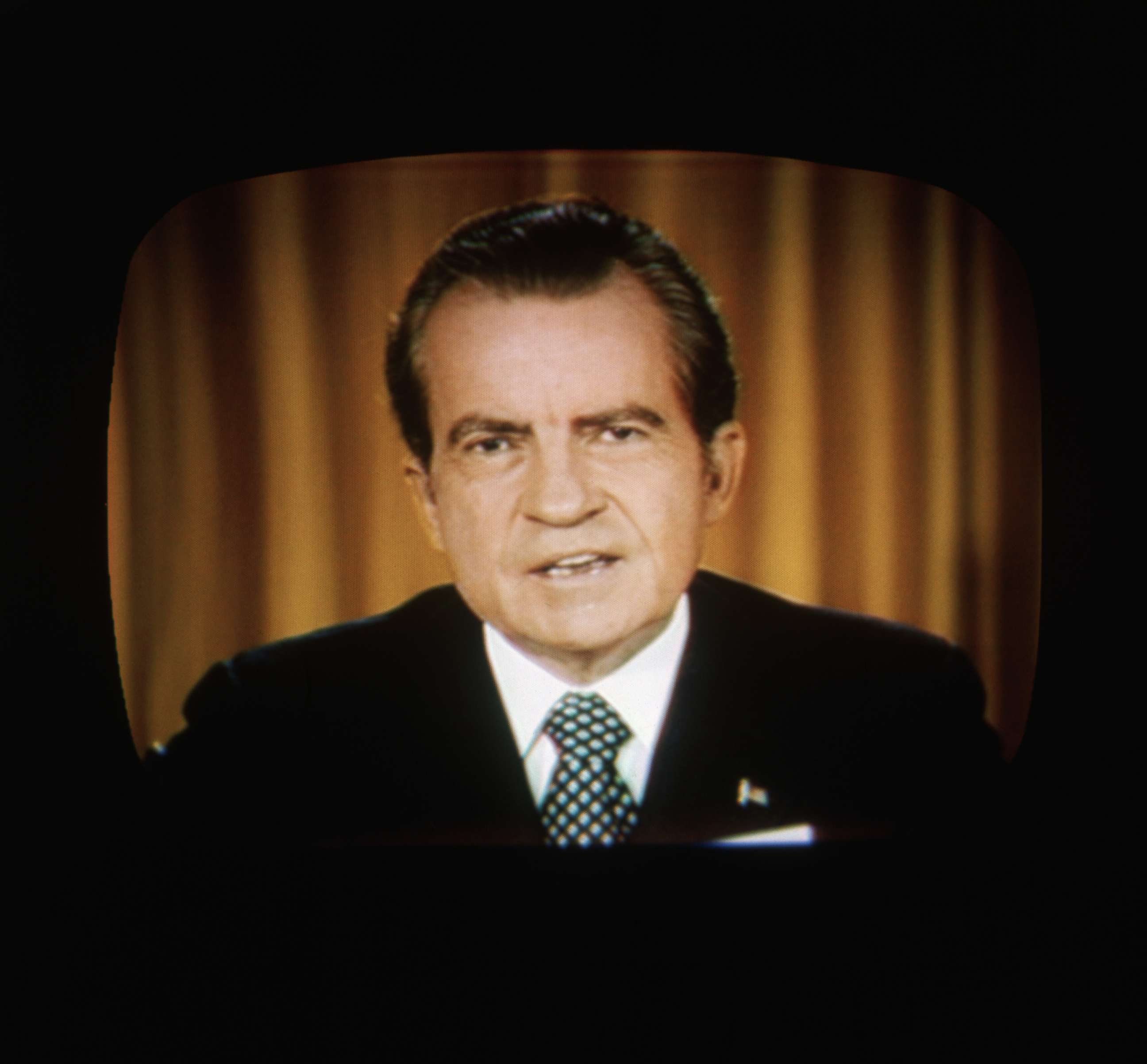

In 1974, President Richard Nixon was ordered to comply with a subpoena for audio tapes in the Watergate case decided by the Supreme Court. Special prosecutor Leon Jaworski sought the tapes as evidence in a criminal trial against seven Nixon aides and advisors, and Nixon’s claims of executive privilege over the recordings were rejected by the justices in a unanimous decision.

Nixon, however, was never subpoenaed for testimony. He resigned the presidency a few weeks after the Supreme Court ruling, rather than face almost certain impeachment.

In 1998, President Bill Clinton avoided a court fight after Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr issued a grand jury subpoena to the president for testimony about his relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Clinton relented and agreed to testify via video from the White House. In exchange, Starr agreed to withdraw the subpoena.

A year earlier, Clinton had been ordered by the Supreme Court to testify under oath in a civil lawsuit by Paula Jones, who had accused Clinton of sexually harassing her while he was the Governor of Arkansas.

Clinton’s sworn testimony in the civil case deposition and during his grand jury appearance eventually led to articles of impeachment, accusing the president of “perjurious, false and misleading testimony,” among other charges. The House of Representatives voted to impeach Clinton, but the Senate failed to convict him.

“It is well established that the president has to comply with a grand jury subpoena for stuff, like documents and tapes, and has to comply with a subpoena for testimony in a civil context,” said Kimberly Wehle, a law professor at the University of Baltimore, who was an associate independent counsel for Starr. “What's not clear is: does the president have to comply with a grand jury subpoena for testimony?”

The prospect of a protracted legal battle over that unanswered question is now hanging over President Trump and the mid-term elections that could shift the balance of power in Congress.

Even as he continues to publicly excoriate the investigation as a politically orchestrated witch hunt, Trump has said he would like to answer Mueller’s questions, but has indicated he will ultimately defer to the advice of his attorneys.

Mueller, meanwhile, has been characteristically silent.

To get a sense of how a court fight over a subpoena might shake out, ABC News spoke with Whiting, Wehle, and four other legal scholars to get their thoughts on whether Mueller could, or should, seek to compel the president to testify, and who would most likely prevail in court.

Is it smart strategy for Mueller to issue a subpoena on the president?

Peter Shane, professor, Ohio State University, Moritz College of Law: “I would say, yes. Because the evidence that the president could give would be, in my judgment, directly relevant to the plausibility of charges that involve not only the president but other people involved in his campaign, including family members. And I think that as a prosecutor and former FBI director that Mueller believes in dotting as many I's and crossing as many T's as possible. I don't think he would want to leave this particular stone unturned.”

Whiting: “There are risks for [Mueller] in terms of whether to seek a subpoena. The first is delay. It would be litigated, and it would take several months to be litigated. So he'd have to decide whether and how the delay would affect his investigation. And the second thing is, he could lose in court. I don't think he would lose in court. But there is always a risk of losing in court. And so he would have to calculate how important it was for him to get the interview versus the risks. That's why this has dragged on for so long. Both sides are negotiating in the shadow of these risks and trying to press their positions and see who will blink first.”

Stephen Saltzburg, George Washington University professor of law, former associate independent counsel: “Better not to [subpoena the president] because it could be litigated for 18 months or more. [Mueller] has sufficient statements by the president to know why he did what he did.”

Wehle: “I'm confident that what's going on inside the [Mueller] investigation is only remotely related to what we know about, at this point. So it's possible he has what he needs and doesn't absolutely need the president's testimony. So he could walk away from it or he could issue a subpoena.”

What would prompt Mueller to issue a subpoena to the President?

Saikrishna Prakash, professor of Law, University of Virginia: “Giuliani has been all over the press about how the president wants to testify but not with respect to all of these questions [about obstruction of justice]. This has been going on for months. Perhaps Mueller believes that he just has to ask these questions and play this out to see what the president’s response is.”

Whiting: “Mueller would have to decide either that Trump's team is not serious about sitting down for an interview or that the conditions they are seeking to impose are so restrictive as to make the interview not worthwhile. And if Mueller decides that one of those two things has happened, then that's when he would have to make a decision about whether or not to seek a subpoena.”

Wehle: “This is all really just a game of chicken. We can go around and around and around, and what all of this comes down to is, the president is saying, 'make me.’

Paul Rosenzweig, Senior Fellow, R Street Institute, Professorial Lecturer in Law at George Washington University: “One of the best arguments against wasting time on subpoenaing the president is that, since there is a [Justice Department] policy that says the president can't be indicted - and Mueller has probably decided in his mind that he's going to follow that policy - it doesn't really make that much difference what the president says. If you're not going to charge him with a crime, who cares what he has to say, right? I think that I care what he has to say, even if it's not capable of being criminally prosecutable, because I think that the truth value of knowing what happened is greater.”

If and when Mueller decides to subpoena President Trump, what happens next?

Wehle: “That's the federal government basically saying, ‘you do this, or else.’ That's what a subpoena is. It is saying to the president of the United States, ‘If you don't comply we, the government, are going to make you comply.’”

Saltzburg: “The president could comply, or he could file a motion to quash [the subpoena] on the ground that it is a burden on the presidency.”

Shane: “The reasons for objecting to the subpoena have to do with whether a president may be subpoenaed for testimony at all. What [the president’s lawyers] are going to say, I’m virtually certain, is that the court has no authority to demand that the president give personal testimony.”

Prakash: “I think the president would then invoke executive privilege. And I think the special counsel at that point would try to contest the invocation, saying it doesn't apply, and therefore the president has to testify. And so that would be litigated, and the court would have to decide whether the special counsel could actually contest the president's claim. If they decide that he couldn't, that would be the end of the subpoena. He wouldn't be able to enforce it.”

Rosenzweig: “If they are at an impasse and Mueller issues a subpoena, the president has a decision to make. He can comply with the subpoena. That means showing up in the grand jury and answering questions like any other human being who is subpoenaed to testify. Option two is the one that President Clinton chose in the 1990’s, which was when he was subpoenaed by Ken Starr. That was when [Clinton’s] team finally sat down and negotiated. The third thing the president could do is fight. He could go to court and say, ‘I'm the president, you can't subpoena me, I refuse to come.’ That fight would start in the District of Columbia where the grand jury is meeting and, pretty obviously, it would go all the way up to the Supreme Court.”

Whiting: “The other thing that could happen is Mueller could issue the subpoena and then that could start negotiations again. If they see that Mueller is willing to issue a subpoena, then they might reassess their risks.”

How long might a Court battle over a subpoena take?

Prakash: “The president will try not to comply with any order until he gets a decision from the [appellate] court or from the Supreme Court. If a district court ordered him to testify, I suspect he'd say, ‘I am going to appeal this,’ and try to prevent the testimony from being given.”

Whiting: “It would certainly be expedited because this is an ongoing investigation. So there is a pressing need to resolve it. And also I think the judge would know that both sides have fully thought through their arguments, because this is no surprise. It's an unresolved legal issue. There are a number of different dimensions to it, but a relatively narrow issue.”

Rosenzweig: “I would expect everybody would work very hard to expedite it as rapidly as possible. And so three months would not be unreasonable. It could take four, could take five.”

Shane: [There’s] an interesting question as to strategy because there are two elements of strategy. Two objectives. One is winning. The other is delaying. It may be that the president will think, ‘we have such great likelihood of succeeding at the Supreme Court, let's get there quickly.’ It may be that Mueller will think it's actually as much in his interest, or maybe more in his interest than the president's, to get this to the Supreme Court quickly. Because he may be relatively confident that, even with a conservative majority on the court, this subpoena will be upheld.”

If the subpoena fight reaches the Supreme Court, who is likely to prevail?

Prakash: Unlike the {Nixon] case, they are not asking for evidence, for documents or tapes. They're asking for the president's testimony. I don't know what the court would say about trying to get the president to testify as to whether he had the requisite state of mind for obstruction of justice, or whatever else the special prosecutor is investigating. And I don’t know what the court would say about the applicability of executive privilege in that context. As far as I can tell, the Special Counsel doesn’t have any [explicit] litigating authority to contest presidential assertions of executive privilege. That was a feature of the regulations in place in the Watergate era. It wasn’t re-adopted, for whatever reason, when the Clinton administration put out these special counsel regulations.”

Shane: “I would be a little surprised if the Supreme Court were to take the position that executive privilege with regard to testimony was absolute. The accountability of any one branch of government to any other branch depends on access to information. And my guess is that the Supreme Court will be mindful of the president's accountability to law in resolving the subpoena question, if it ever gets that far.”

Whiting: “I don’t think there is any way that the court is going to find that a president is categorically protected from responding to questions from a grand jury in a criminal investigation. I think what's going to happen is - the decision is not going to be, ‘you can never subpoena the president.’ And it's not going to be, ‘you can subpoena the president just like any other citizen.’ It's going to be somewhere in the middle.”

Rosenzweig: “In the end my prediction is, 75 to 25 [percent], that Mueller wins. And the reason is that all of the cases have said that the president cannot resist subpoenas except in cases of grievous national security and very particular reasons not to. This ain’t that. So I think Trump loses in the end.”

Could Trump defy a court order to testify?

Rosenzweig: “What if he just says, ‘no?’ If he just says, in the parlance, ‘[expletive] you?’ People who ignore subpoenas are held in contempt by the judge and the grand jury. And then, in the normal course of business, the judge orders the US Marshals Service to go out and arrest that person. You can immediately see why that would be a bit of a problem.”

Wehle: “Who is going to push back if this president doesn't play ball? Who actually would enforce a contempt order for non-compliance with a grand jury subpoena? It would be the United States Marshals Service, which is within the executive branch, Article 2 of the Constitution. Who is in charge of executive branch of Article 2 of the Constitution? It's the President of the United States.”

Prakash: “Forget for a moment the obstruction of justice [allegations] and the Russia stuff. If you fail to obey a decision of the Supreme Court, he could be impeached for that by itself. I’d be very surprised if he said, ‘I’m just not going to do it.’ Even if the court says, ‘executive privilege just doesn’t apply here, Mr. President, you lose on this,’ the president always has the Fifth Amendment [right] against self-incrimination. Invocation of the Fifth Amendment would be politically damaging, because many people assume that if you are invoking [it], you must have done something wrong.”

Rosenzweig: “I could imagine a confrontation in which a court holds him in contempt. But I can’t imagine that anybody would actually send the marshals to arrest him. So then it would probably become really just a political question. At what point do the political factors engage themselves in a way that forces the president to comply?”