Monkeypox cases surpass 1,200 globally, but experts say the outbreak is 'controllable'

Cases of monkeypox are continuing to crop up around the globe as the outbreak of the rare disease keeps spreading.

As of Thursday, at least 1,260 cases have been detected in countries where the virus is not endemic, with the overwhelming majority reported in North America and Europe.

São Paulo authorities confirmed to ABC News Wednesday that the first case of monkeypox has been confirmed in Brazil in a 41-year-old man who recently traveled to Spain.

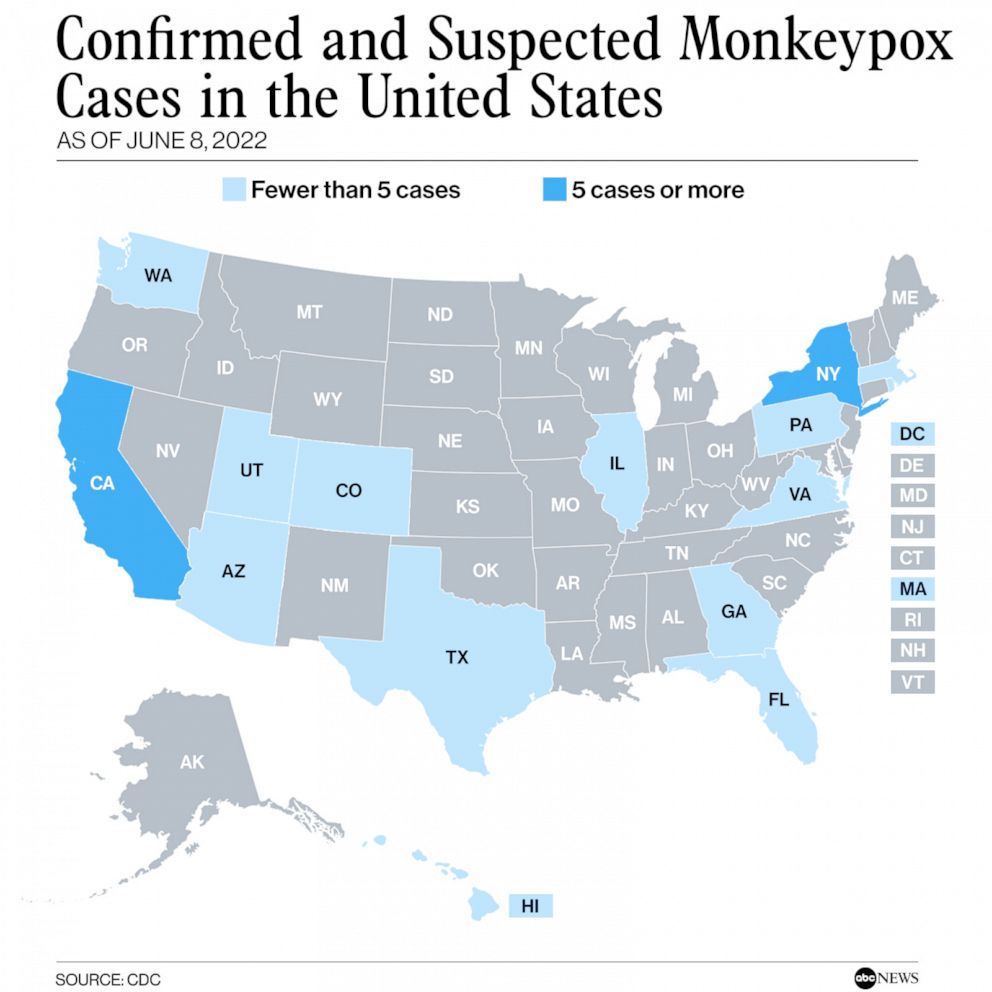

In the United States, 40 infections are suspected or confirmed in 14 states and the District of Columbia, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New York has the most cases at nine, followed by California with eight, Florida with four, and Illinois and Colorado with three each.

During a briefing Wednesday, World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said the window of opportunity to contain the outbreak is closing.

"The risk of monkeypox becoming established in non-endemic countries is real," he said. "But that scenario can be prevented. WHO urges the affected countries to make every effort to identify all cases and contacts to control this outbreak and prevent onward monkeypox spread."

Public health experts currently do not expect the virus to become a major health threat, but are concerned about the recent spread.

"I think any time there's an outbreak that is ongoing with no evidence of control, I think we should be concerned," Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, a professor of epidemiology and medicine at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, told ABC News. "I think that's different from being panic-stricken. But I think the continued increase in numbers of cases of monkeypox and continued increase in countries reporting cases is certainly of concern."

If the outbreak isn't contained, this means the virus could be ever-present in a community, circulating at low levels.

But Dr. Scott Roberts, an assistant professor and the associate medical director of infection prevention at Yale School of Medicine, said he does not envision the outbreak as being similar to the COVID-19 pandemic because of the different mechanisms of spread.

COVID-19 generally spreads through the air via tiny droplets and can require as little as 15 minutes of face-to-face contact. In the current outbreak, most of the spread has come from coming into contact with infected people's lesions.

"It's not like you'll pass someone in the elevator, and you'll get monkeypox," Roberts told ABC News. "That's pretty unlikely. The classic COVID definition was within six feet for 15 minutes. This one is more like within six feet for three hours, is what the CDC has said, or contact with the infected lesions."

Many cases have been reported among men who identify as gay, bisexual or men who have sex with men, but there is currently no evidence monkeypox is a sexually transmitted infection -- and the experts emphasize anyone can be infected.

But, most importantly, they said the virus is not spreading uncontrollably yet.

"The important thing to keep in mind is that it's a containable outbreak," Dr. Mark Dworkin, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Illinois Chicago, told ABC News. "There have been outbreaks and they have been successfully controlled."

Dworkin referenced a 2003 outbreak in which 47 confirmed and probable cases were reported among six U.S. states, the first human cases reported outside of Africa.

All the infections occurred after coming into contact with pet prairie dogs, which became infected "after being housed near imported small mammals from Ghana," according to the CDC.

"We have a relatively strong public health system for dealing with this kind of problem," Dworkin said. "We had a monkeypox outbreak that was multi-state and successfully controlled without the use of a vaccine but through contact tracing and isolation so I'm optimistic."

Currently, there are two smallpox vaccines approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that people who have been exposed to monkeypox can take to reduce their risk of infection.

"The thing with monkeypox is it's a very long incubation period," said Roberts. "It's usually one to two weeks, but it can be up to three weeks between getting exposed and having symptoms."

He continued, "So that actually gives you a window to vaccinate after you've been exposed to ramp up your immunity and really get rid of the virus before it becomes a true blow infection."

The CDC has previously said the federal government has enough vaccines and treatments for anyone who is exposed but is not recommending a mass vaccination campaign at this time.

ABC News' Aicha Elhammer contributed to this report.