Mom helps kids of imprisoned parents after her husband was convicted of murder

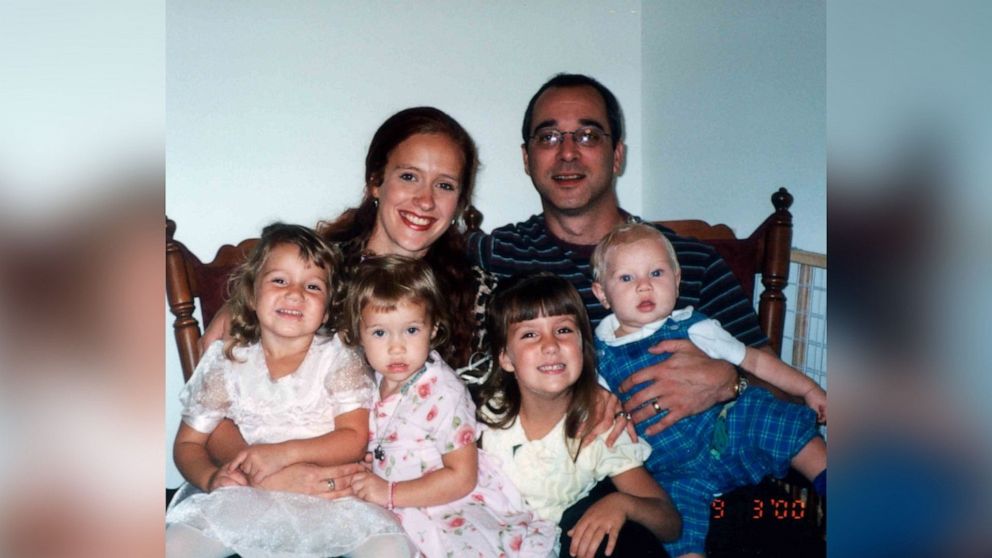

Rebecca Simic thought she had found the perfect life. She had four healthy, beautiful children, a loving husband with a good job and a house in the countryside.

But on June 5, 2002, that illusion was shattered when her husband, Mark Winger, was convicted of murdering his first wife seven years earlier.

At first, the August 1995 murder of Donnah Winger in her Springfield, Illinois, home appeared to be a tragic event with a simple explanation: she had supposedly been bludgeoned to death by Roger Harrington, a driver who had recently shuttled her home from the airport and whose behavior during the ride had made Donnah fear for her safety.

Watch the full story on "20/20" TONIGHT at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

Winger told police that he’d discovered Harrington attacking his wife with a hammer and that he fatally shot him. Police accepted Winger’s horrifying story of a home invasion by an unhinged man and quickly closed the case.

Simic was 23 years old and recently graduated from college when she was hired by Winger a few months after the murders to be a live-in nanny for his infant daughter Bailey.

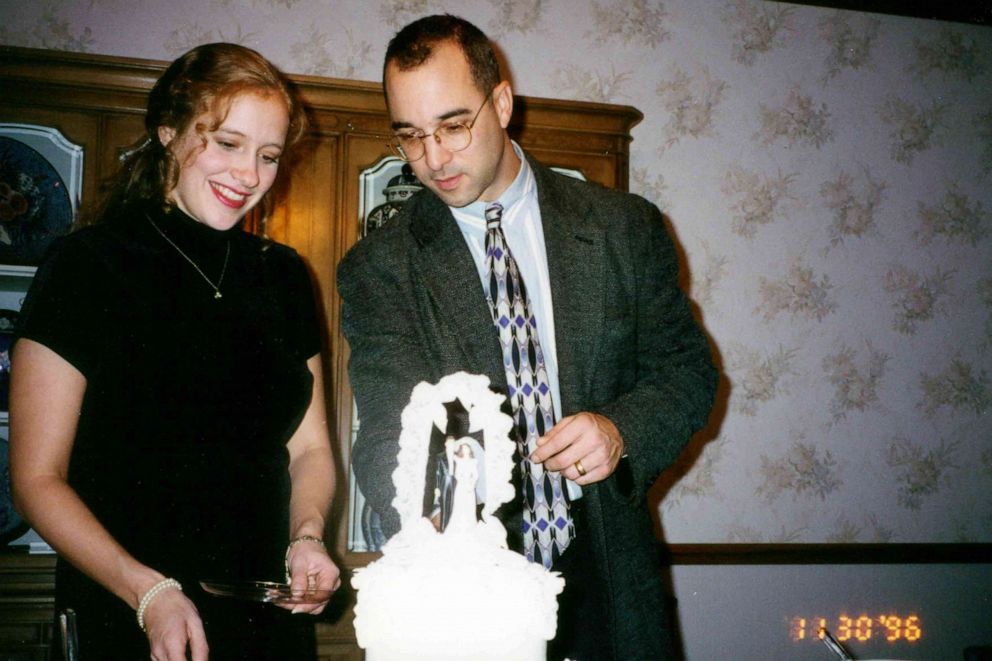

Winger and Simic’s relationship soon became romantic and within a year, they were married. Simic legally adopted Bailey, whom she had already grown to love as her own daughter. Like the police, she believed Winger’s story about his first wife’s tragic death.

Over the next four years, Simic and Winger had three more children together and moved to a farmhouse outside the city to accommodate their quickly growing family.

But during this time of domestic bliss, authorities had reopened the investigation into Donnah Winger and Harrington’s deaths. Investigators uncovered previously overlooked evidence and also learned that Winger had been cheating on Donnah. That new information revealed a starkly different picture of the tragedy inside the Winger home on that day in 1995.

The façade of Mark Winger as a heroic widower had begun to crack, and it fully crumbled away in August 2001 when he was arrested and charged with murdering Donnah Winger and Roger Harrington. After a public and painful three-week trial, a jury found him guilty of two counts of first-degree murder.

Simic remembers being in the courtroom for that moment which changed her life.

“That guilty verdict solidified that, ‘Hey, your life's over. Your kids don't have a dad. It's up to you. Move on,’” she said.

When she’d first entered Winger’s home in 1996, Simic described herself as a young woman with the world at her hands who aspired to help people and work with children. And she had found that, perhaps not the way she expected, as a loving wife and mother helping to mend a household broken by tragedy.

After her husband’s conviction, she found herself saddled with a new identity that was both unwanted and unrecognizable: a single mother to four young children and the wife of a convicted murderer, surrounded by a community that she felt viewed her as guilty by association.

At the time, she also worried about how Mark Winger’s crimes might stigmatize their children: Bailey, 7, Anna, 5, Maggie, 3 and Ben, 2.

“That guilty verdict was handed down to my kids and I too,” she said. “It wasn't just him being sentenced to life. We were sentenced too.”

In desperate need of a fresh start, the family left their life in Springfield behind and moved away to live with Simic’s brother, Steve Simic, as she worked to get back on her feet and build a career of her own.

Simic divorced Mark Winger and legally changed her and her children’s names from Winger to Simic, her maiden name. It was a symbolic step in her journey to, as she describes it, “be seen for who I am and not who he was.”

Although they now lived in a new city and were freed of Mark Winger’s name, Simic found it much harder to shed the stain left from his crimes.

Along with the loss of her marriage, she also lost her financial security. Trying to find a job after seven years as a stay-at-home mom and her home in foreclosure, she found herself making the painful decision to go on welfare.

At the same time, her children were also growing up fast and they began to gain a better grasp about why their father was in prison. She worried how the trauma and shame might affect them.

Bailey, now 25, remembers the day her mom sat her down and told her about her father’s crimes. As a preteen still struggling with her father’s absence, it allowed her to close the door on those unresolved feelings: “It kind of just told me all I needed to know to just break things off.”

Simic strived to create normalcy and happiness for her children while privately struggling with her own grief. “When we lose someone, we gather and we remember them and we tell stories and we have a funeral,” Simic said. “But when someone goes to prison, well, what do you do? I mean, you can't grieve them. They're still here… You're just kind of left with this emptiness.”

Out of that emptiness, Simic found herself on a path that she could never have imagined, without a road map or a guidebook. It also made her a member of an enormous club that often remains hidden, of families left behind when a parent goes to prison.

It opened her eyes to the silent struggle of countless families, she said.

“You don’t know what they look like. You don’t know what side of town they live in,” Simic said. “I'm not special. There's a million moms doing this a million different ways, a million different days.”

Today, Simic’s four children are thriving young adults who have spanned out across different states to pursue careers and higher education.

Bailey manages a restaurant and hopes to run her own animal sanctuary one day. Anna, now 24, teaches seventh and eighth grade English. Maggie, now 22, is an artist who works with fibers and beads. Many of her pieces deal with her family story, in particular a memorial shrine she built to honor her father’s victims.

With her own kids safely past the hurdles of childhood and adolescence, she has now focused her maternal energy on supporting other children growing up with incarcerated parents. She is collaborating with the mentorship program Big Brothers Big Sisters and volunteering alongside her son Ben, who at 21 stands 6 feet, 4 inches tall, is a forward on his college basketball team.

She knows that many kids of incarcerated parents may not have a supportive, loving home like her children did.

A simple message that she wants to pass on to these children, as she did to her own, is that they get to define who they are.

“It’s not about what your parents may or may not have done,” she said. “It’s about what you’re going to do.”