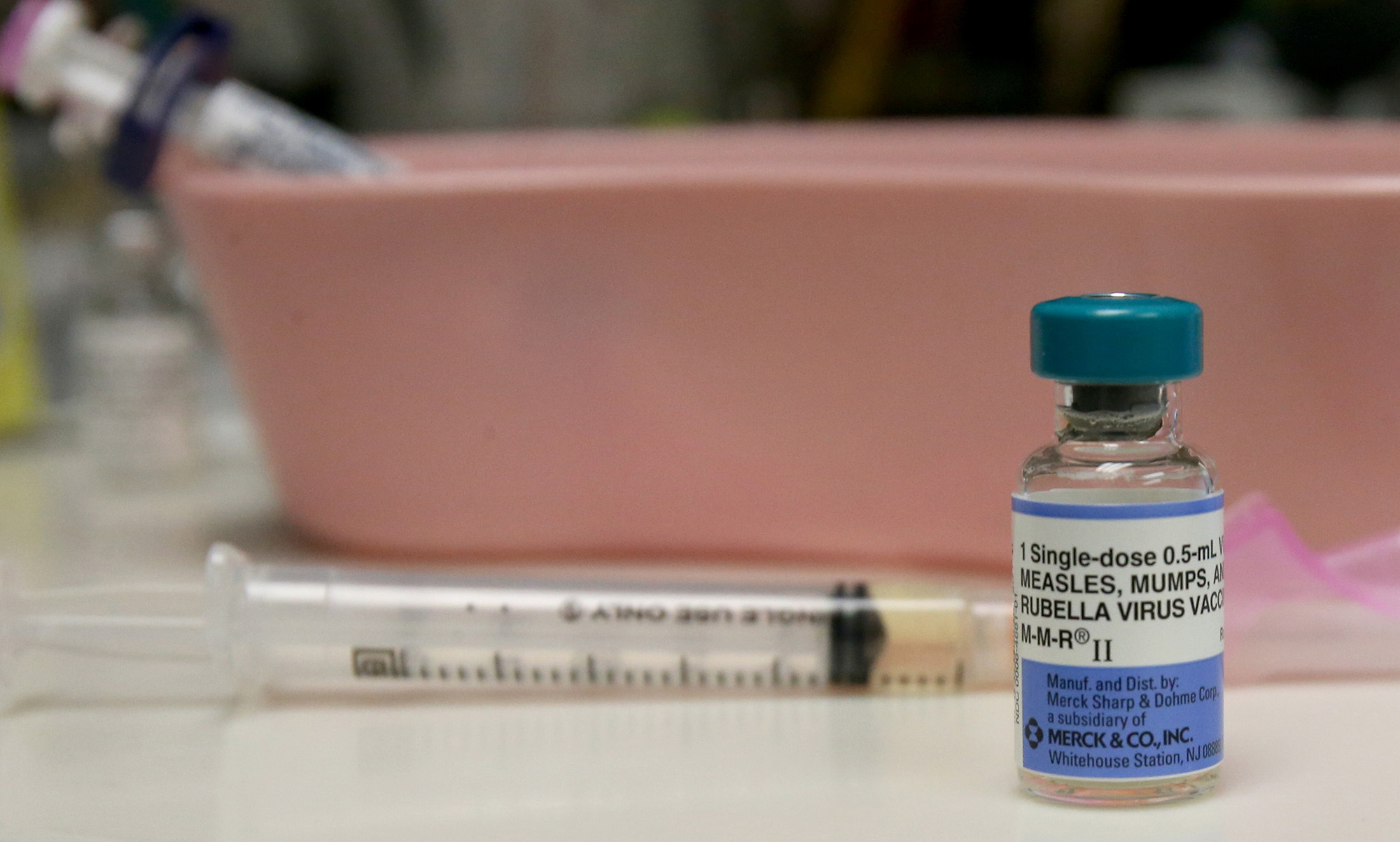

MMR vaccine rates are lagging amid a rise in measles cases. Experts blame a discredited study.

When a measles outbreak struck Columbus, Ohio, late last year, public health officials learned the overwhelming majority of cases -- 80 of 85 -- were among unvaccinated children.

Investigators from Columbus Public Health went to speak to parents to ask them why they hadn't vaccinated their children with the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) shot or why they were delaying vaccination. What they found was surprising.

"What our team heard from many parents is that they weren't necessarily against vaccines and their children had other age-appropriate vaccines, but they were specifically putting off the MMR vaccine or waiting as long as they could before they had to get it because of fears it could lead to autism," Kelli Newman, director of public affairs & communications for Columbus Public Health, told ABC News.

What Newman is referencing is a myth that was born out of a now-debunked paper from the U.K. in 1998, which allegedly found that MMR vaccines cause autism.

The paper has since been discredited by health experts, retracted from the journal in which it was published, and its primary author, Andrew Wakefield, lost his medical license. More than a dozen studies have since tried to find a link and have not been able to do so.

However, the damage has been done. Numerous outbreaks of measles have popped up -- in the U.K. and in the U.S. -- over the last two decades, vaccination rates have fallen from their peaks and a recent Gallup poll found 10% of Americans do think vaccines cause autism.

"We eliminated measles from the United States in the year 2000 and since then, measles has become back," Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in division infectious diseases at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, told ABC News.

He added, "I think the summary of all that for me is that while it's very easy to scare people, it's hard to unscare them."

What is the 1998 study and what did it say?

Wakefield and his colleagues published a case study in the medical journal, The Lancet, in 1998, hypothesizing that the MMR vaccine caused intestinal inflammation, which, in turn, led to the development of autism.

In the case study, Wakefield presented 12 children who had all recently received the MMR vaccine and complained of intestinal issues. Eight of those children then developed autism within a month of getting the MMR vaccine.

Offit said the study was a clear example of correlation without causation.

"He might as well have done a case series of eight children who had recently developed leukemia after eating a peanut butter sandwich, it was really that level of science," Offit said. "It was an irresponsible publication, and it set off a firestorm."

According to the Nuffield Trust, an independent health think tank, before the 1998 paper, MMR vaccination rates in the U.K. were 91%. However, by 2004, vaccination coverage had fallen to as low as 81%.

In the U.S., 90.8% of children aged 24 months have received at least one dose, higher than in recent years but not as high as the peak of 91.5% in 2003, according to the CDC.

Additionally, only 93.5% of kindergartners received the two-dose vaccine for the 2021-22 school year, the lowest percentage seen in at least 10 years, CDC data shows -- although some of this may be a factor of pandemic-related delays.

Wakefield is discredited

In February 2004, The Sunday Times published an investigation, accusing Wakefield of a conflict of interest.

It alleged some of the parents of the children in the paper were suing vaccine manufacturers prior to its publication and Wakefield had received funding to try to find a link between the MMR vaccine and autism, which was not disclosed in the Lancet article.

This led to 10 of the 13 authors withdrawing their support.

Another investigation by the same journalist found that a year before the paper, Wakefield had filed a patent for a single dose MMR vaccine touted to be "safer" than the current two-dose vaccine, raising further questions about his motivations.

In 2007 the General Medical Council, which regulates physicians in the U.K., opened an investigation. It was discovered that Wakefield had misrepresented the medical data. Some of the children in the paper had received the vaccine after they had already developed signs or symptoms of autism.

The Lancet officially retracted the paper in February 2010. Three months later, the GMC ruled that Wakefield had acted "dishonestly and irresponsibly" in conducting his research. He was struck off the U.K. medical register and barred from practicing medicine, effectively ending his career as a physician.

Wakefield has continued to stand by his research and the 1998's paper's findings. He has denied the accusations of fraud or that he sought to earn a profit from the subjects of the study.

However, vaccine experts said Wakefield received the criticism he deserved.

"This paper has been rightly disparaged, it is recognized as fraudulent," Dr. Gregory Poland, head of the Mayo Clinic's Vaccine Research Group, told ABC News. "He was stripped of his medical license. I mean, there could be no greater censure of the medical profession upon him than this, to recognize the fraud inherent in this article and the incredible damage that it's done."

Why measles can be so dangerous

"If I have the opportunity to speak with parents, I not only go through the overwhelming evidence showing there's no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. I also talk about measles," Dr. Peter Hotez, co-director of the Texas Children's Hospital Center for Vaccine Development and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine told ABC News.

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known to humans. According to the CDC, just one infected patient can spread measles to up to 10 close contacts, especially if they are not wearing a mask or not vaccinated.

Complications from measles can be fairly benign, such as rashes, or they can be more severe, including viral sepsis, pneumonia or brain swelling, or encephalitis..

In the decade before the measles vaccine became available, an estimated 3 to 4 million people were infected every year, 48,000 were hospitalized and between 400 and 500 people died, according to the federal health agency.

By comparison, complications caused by the MMR vaccine are so few and far between that Hotez calls them a "pinprick" compared to complications from measles.

According to the CDC, one dose of the MMR vaccine is 93% effective and two doses are 97% effective.

"Is getting these diseases 'naturally' healthy for you? No," said Poland. 'There are documented probabilities of complications and even deaths. Are vaccines perfect? No manmade product is."

"But wisdom resides in the balance of risks and benefits and that balance falls heavily and markedly decidedly in favor of vaccines," he added.

What we know about autism

Wakefield has never been able to replicate his findings and numerous studies and meta-analyses have found that MMR vaccines does not cause autism.

According to the CDC, several factors have been identified as potential risks of autism including biological, environmental and genetic factors.

Hotez, whose youngest daughter, Rachel, has autism and intellectual disabilities, said knowledge of what can cause autism has increased in several years.

"We've now identified about 100 genes that are involved in autism, a lot of them were identified by the Broad Institute at Harvard, MIT," he said. "And we actually did whole genomic sequencing on Rachel, my wife and I, to identify Rachel's unique autism gene."

Hotez also noted that some people have cited the rise in autism incidence as proof of vaccines causing autism. But he argues that this rising incidence is actually indicative of how clinicians have become better at diagnosing autism and enlarging the criteria for which someone is put on the autism spectrum.

To combat some of the misinformation out there, Hotez even wrote a book, which he titled "Vaccines Didn't Cause Rachel's Autism", and cited a cohort of studies showing children who received the MMR vaccine were no more likely to have autism than children who didn't receive the MMR vaccine.

"It's about as airtight as you can get that there's just no link between the MMR vaccine and autism," he said.

How to convince parents to vaccinate their children

There have been a multitude of outbreaks since the Wakefield paper. From December 2014 to April 2015, there was an outbreak that began at Disneyland Resort in California.

Additionally, there was the 2019 outbreak that impacted mainly the Pacific Northwest and New York, in which 1,274 were confirmed in 31 states, the greatest number reported since 1992.

Of course, most recently was the Columbus, Ohio, outbreak. Experts say there will be more in the future, if pockets of unvaccinated people remain and with the spread of anti-vaccine sentiment.

"It always has, it always will," Poland said. "And as immunizations rates fall, because there are no requirements because of delays due to the pandemic, we will lose what has been built up in that so-called herd immunity."

Offit said he speaks to parents all the time who are hesitant or skeptical about vaccines, but the important thing is to address each of their questions and concerns with as much care as possible.

"People really do at the end want to trust their doctors," he said. "I mean when they're sick, they're not going to go to Andrew Wakefield, they're gonna go to their doctor."

Newman, from Columbus Public Health, said officials took a multi-pronged approach including outreach and engagement in the community and emphasizing the importance of vaccination. One mother even expressed that she regretted not having gotten her child vaccinated.

Offit added that vaccines have made us forget the complications that diseases measles, polio and smallpox used to cause.

"The outbreaks in Columbus, Ohio, for example, a couple dozen children were hospitalized. That is a dangerous game to play," he said. "A choice not to get a vaccine is not a risk-free choice. It's your choice to take a different risk and more serious risk and unfortunately, we're learning about what those risks look like."