Mexican elections are bloodiest in recent memory

In Mexico, money in politics is a matter of life and death.

More than 100 people have been killed in connection with Mexico’s upcoming elections on Sunday, according to a study conducted by the Mexico City-based consulting firm Etellekt, an unprecedented level of violence fueled by the country’s powerful drug cartels.

Local politicians have borne the brunt of the brutality as criminal organizations in regions where the cartels have largely replaced the government as the dominant force in public life fight to place candidates loyal to their interests into office -- often by eliminating the opposition.

Cartels compete for power by financing local elections with “dirty money” and use violent means to protect their investments, undermining the very fabric of Mexico’s political system, according to Edgardo Buscaglia, a senior research scholar in law and economics at Columbia Law School.

“I would not call Mexico a democracy,” Buscaglia told ABC News. “I would call Mexico a 'mafiocracy.'”

Between the opening of candidate registration in September and the close of campaigning on Wednesday, the study recorded 132 political assassinations, including many candidates or pre-candidates -- the equivalent of politicians vying to become nominees in U.S. primaries -- as well as dozens of additional assaults, kidnappings and threats. The vast majority of murders were related to local elections; the tally comprised of 105 municipal-level cases, 26 state-level cases and one federal-level case.

More than half of the cases were concentrated in just five states -- Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, Mexico State and Veracruz -- most of which are well-known hubs for organized crime.

The assassinations have marred the electoral season with a slew of increasingly grim headlines.

Earlier this year, Dulce María Rebaja Pedro, a government official and local deputy pre-candidate, was kidnapped with her cousin in Chilapa; their bodies were discovered riddled with bullets in the bed of an abandoned pickup truck, according to Proceso, a local newspaper.

Earlier this month, federal deputy candidate Fernando Purón Johnston was shot and killed as he was leaving a debate at a university in Piedras Negras. The assassination was captured by the school’s security cameras, according to local news outlet El Financiero.

And just this week, in perhaps the bleakest indicator of the depths of corruption in local politics, the Washington Post reported that state authorities in Michoacan detained the entire police force of the town of Ocampo -— about 30 officers -— for questioning on the suspicion of their “complicity” in the murder of a local mayoral candidate.

The Mexican political system suffers from a “complex cancer,” Buscaglia said, in which threats of or actual violence scares the “good guys” into silence.

A spokeswoman for the office of President Enrique Pena Nieto could not be reached by ABC News.

Organized crime injects so much money into public institutions and local economies, Buscaglia said, that it functions as a shadow state in areas of the country where the federal government is weak, perpetuating an illicit system of patronage politics and eroding what little political will remains for reform.

Honest candidates or prosecutors who would seek to challenge that system face extreme pressure to keep quiet from both inside and outside of government, he added.

“Many honest people are afraid,” Buscaglia told ABC News. “They know that if they start to apply tools that other countries have applied to clean up this mess, immediately they will be isolated politically or threatened or killed.”

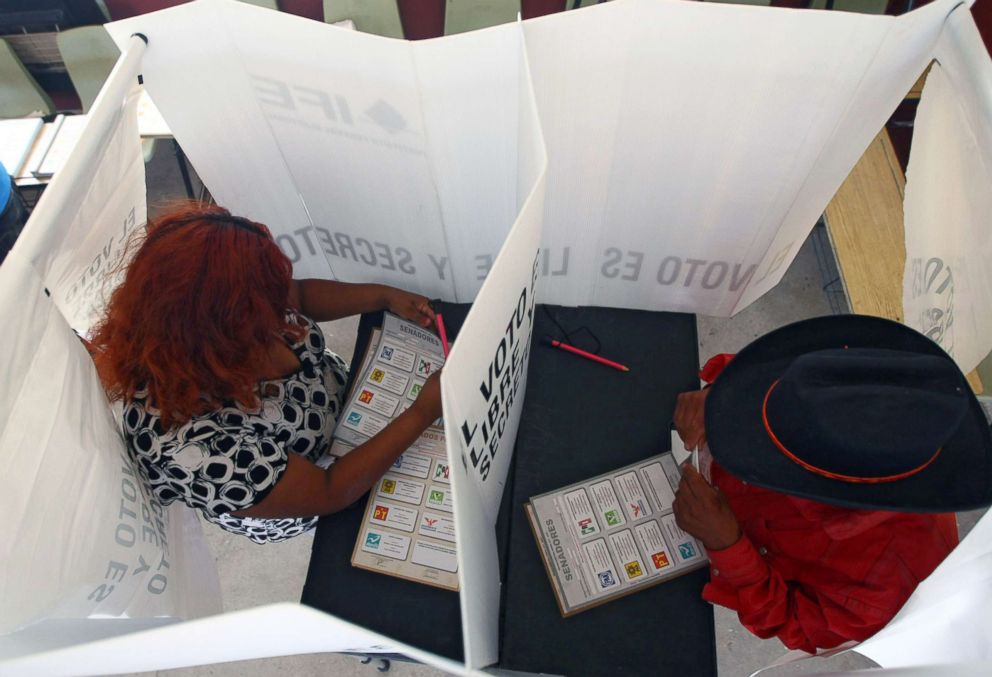

Still, Mexicans will head to polls Sunday and vote for candidates who have run despite the risk.

Nestora Salgado lives with her family in Seattle but is running for senate in her home state of Guerrero. Salgado -- previously the leader of a community police force -- has been sharply critical of both the drug cartels and the governments allegedly aligned with them, a position she says recently led to her unlawful arrest and brief imprisonment.

“It is very dangerous, I know, but somebody has to do something," Salgado told ABC News. "Nobody is doing nothing. Don’t do nothing, and people start dying every day.”

She will have to move back to Guerrero if she wins the election. Salgado says she is afraid, but doesn’t believe that fear should keep her quiet.

“I am scared, because I am human,” Salgado said. “It is why I have to speak.”

ABC News’ Dan Harris and Joshua Hoyos contributed to this report.