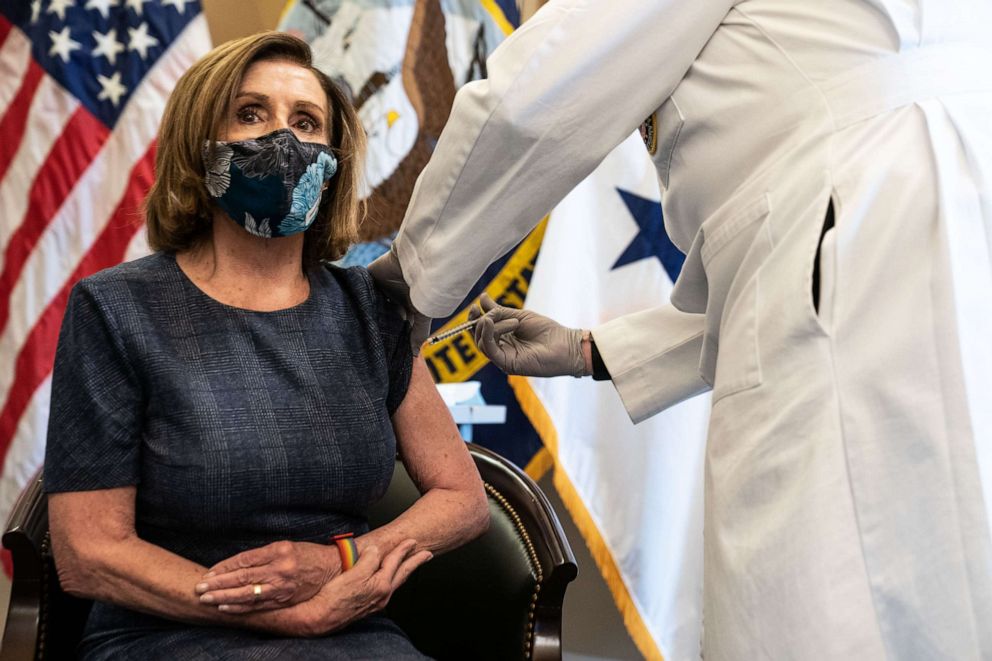

Members of Congress send mixed messages on getting vaccinated

In the week since members of Congress were offered vaccines, moral schisms have emerged on Capitol Hill about whether politicians deserve the shots ahead of their own constituents, particularly doctors and nurses working on the front lines.

On both sides of the aisle, some members have responded by declaring that they won't get the vaccine yet because they don't want to "cut the line." But their decisions defy national security concerns and public health recommendations, according to infectious disease experts across the country.

The vaccine became available to Congress about a week before Christmas, after the National Security Council announced Congress would be allotted doses of the vaccine to protect "continuity of government operations."

"If they were considered a priority to keep the country going, then they need to take the vaccine so they can be healthy and well to keep the country going," said Dr. Simone Wildes, an infectious diseases physician at South Shore Health in Massachusetts and an ABC News medical contributor.

While frontline workers are desperate to get the vaccine, she said, a handful of members deciding to defer their vaccinations is not going to put significantly more vaccines in the arms of doctors and nurses, especially now that Congress has already been allotted doses.

"It has to be a greater movement saying, you know, Congress decided to say we're not going to take the vaccine yet, we want everybody else ahead of us getting the vaccine. That would be a greater stance,” Wildes said.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation's leading infectious disease expert and a member of the White House coronavirus task force who will continue to advise the White House during the Biden administration, has also urged each member to get the vaccine quickly.

"It really is a security issue," Fauci said during a Tuesday interview on Fox News.

Still, there has been a bipartisan showing of senators and representatives who have said they won't yet take the vaccine -- not because they're worried about the vaccine's safety -- but because they want to let others get it first.

Democratic Rep. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota said it was "shameful" for members of Congress to get vaccines ahead of frontline workers and declared that she would wait until they do to get her own. Republican Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas, Rick Scott of Florida and Democratic Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii have each separately pledged the same.

Scott, in a statement, said he'd asked that his "office's allotment be given to vulnerable populations that need the vaccine most," though it's unclear if he has any control over that.

Others have been very clear that in getting the vaccine, their intention is to promote trust in it, particularly within minority communities -- something that public health experts support. That includes 31-year-old New York Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who tweeted: "Our job is to make sure the vaccine isn’t politicized the way masks were politicized....Leaders [should] show we won’t ask others to do something we wouldn’t do ourselves."

Alta Charo, a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin who consulted on guidelines for prioritizing the COVID-19 vaccine for the National Academies of Science, said showing confidence in the vaccine is good reason for elected officials to be vaccinated early in the process. This may be especially true for Republican leaders. A December poll from ABC News/Ipsos showed Republicans were four times as likely as Democrats to say they would never get the vaccine.

"The amount of vaccine hesitancy that has been created in the last 20 years, 25 years is profoundly disturbing and goes deep into our society. So it takes a long time to build up confidence for people, and people who are unsure," Charo told ABC News.

The need to shore up the number of people who get vaccinated could be even greater if more contagious strains of the virus spread, said Dr. William Schaffner, professor of Preventive Medicine and Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. It was reported in the U.K. this past week that a new strain has the potential to spread faster, though scientists said it does not appear to be deadlier or resistant to the vaccines.

"I would like everybody to get vaccinated just as quickly as possible," Schaffner said.

Not all lawmakers who are waiting to get the vaccine are claiming they're doing it so others can go first. Republican Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, who has wrongly urged people who already had the virus to stop wearing masks, said he won't be taking the vaccine just yet because he's already had coronavirus and believes he is still immune.

"It is inappropriate for me -- who has already gotten the virus/has immunity -- to get in front of elderly/healthcare workers," Paul tweeted last week.

But that, too, goes against public health advice. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that even Americans who have had the novel coronavirus should get the vaccine, and they make no suggestion that those people should step back to let others get vaccinated first. And Paul, as with the other members of Congress, has been recommended to get the vaccine to ensure the continuity of government.

Schaffner, who helped craft the CDC guidance for vaccine prioritization, said it recommends that people who have previously had the coronavirus should still get the vaccine since there is no well-established guidance on how long immunity lasts. Some doctors believe antibodies only protect people who have had the virus for about 90 days, putting Paul, who got the virus in March, far beyond the period of immunity.

"Let's not make an opera out of this. The CDC's recommendations about how the vaccine should be used make no provision for people who've previously had COVID," he said, and make no mention of deferring, which he said there was "no need for."

While the U.S. coronavirus response has been disjointed and confusing for Americans trying to follow the most up-to-date guidance, the vaccine provides a rare opportunity to present a united front, Schaffner said.

"There's been so much inconsistency in the messaging about our response to COVID. From the beginning, for months. If we could get together in supporting the vaccine, that would help," he said.

ABC News' Allison Pecorin contributed to this report.